Queer cinema lessons from 1919

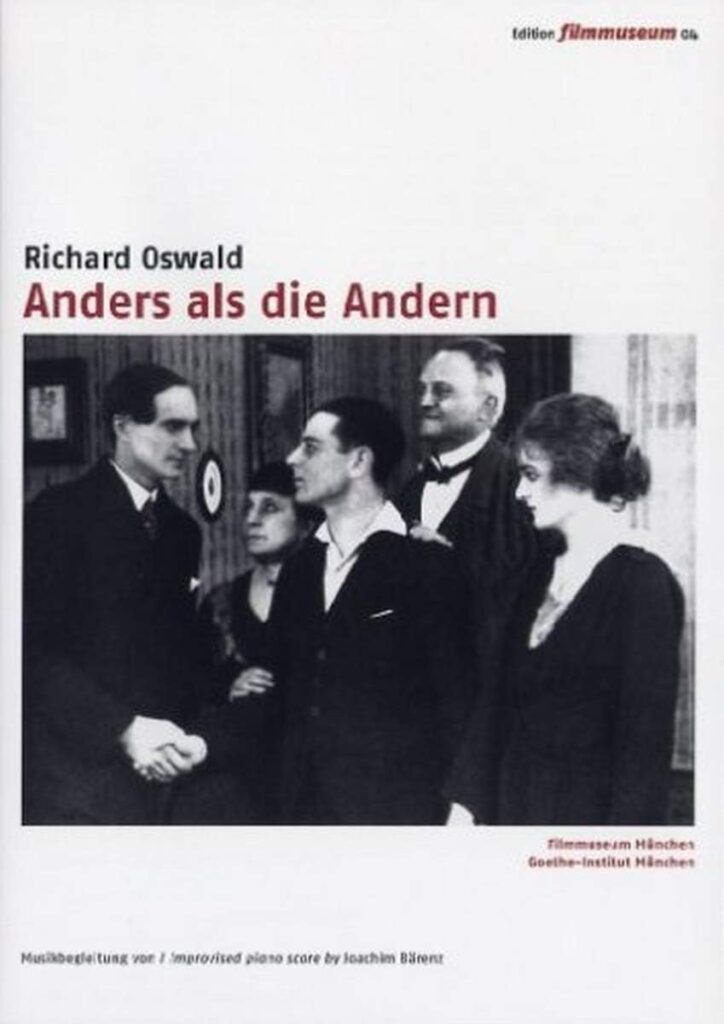

Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others)

by Ervin Malakaj

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023

$19.95 / 9780228018681

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

Queer Film Classics is a series of books examining queer films that have gained iconic status over generations, drawing widespread interest across pop culture and academia. Published by McGill-Queen’s University Press and edited by Matthew Hays and Thomas Waugh, previous titles include studies on Midnight Cowboy, Orlando, and Boys Don’t Cry. This latest instalment, by UBC German Studies assistant prof Ervin Malakaj, goes back more than a century to explore the first known filmic treatment of homosexuality as primary subject matter.

Anders als die Andern, or Different from the Others (DFO), was directed by Richard Oswald, who co-wrote the film with renowned German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. Released at the dawn of the Weimar Republic in 1919, it was produced during a brief window of free expression post-First World War while Germany had lifted its censorship laws. Malakaj examines DFO as a profoundly important work of pre-Stonewall queer consciousness. A stark reminder of how hostile the world has always been to LGBTQ+ people, it’s also a lesson in how to find sustenance and social connection from tragic narratives. As he argues persuasively—and as I can attest, having seen it—DFO draws highly emotional responses from contemporary viewers all too familiar with its theme of societal hostility toward LGBTQ+ people.

The story centres around the relationship between accomplished violinist Paul Körner and a young fan, Kurt Sivers. After Sivers attends one of Körner’s concerts and shares his desire for a career in music, Körner takes him on as a student and the two become lovers. Sivers’ parents disapprove of their son’s ambition and are suspicious of Körner—to whom Sivers’ sister, Else, is also attracted. One day, as the two men enjoy a walk in the park, they are spotted by Franz Bollek, a creepy extortionist who had previously taken advantage of Körner. Bollek blackmails him again because of Sivers. When Körner stops paying Bollek and reports him to police, Bollek reports Körner for violating Paragraph 175 of the German penal code, which criminalized male homosexuality. Bollek gets three years in prison and Körner only a week, but Körner’s suffering is greater because his career is destroyed, his reputation ruined, his family unsupportive, and his lover out of the picture (Sivers runs away after discovering Körner’s previous connection to Bollek). With even his father telling him to “do the right thing,” which in 1919 Germany meant killing himself, Körner sees no alternative but to do just that.

The protagonist’s suicide bookends a story that began with the lonely musician reading newspaper accounts of single, unmarried men who have mysteriously killed themselves. With melodramatic effect, Oswald has Körner realize the cause of these deaths: looking up from the newspapers with dread, he envisions a procession of famous gay men throughout history—including Tchaikovsky, da Vinci, Wilde, and Kings Friedrich II (Prussia) and Ludwig II (Bavaria)—who have succumbed to the pressures of living in a world hostile to homosexuals.

*

This tightly-written, 131-page extended essay contains 11 pages of references well-mined from film theory and queer theory in both English and German. Its three chapters cover the film’s production, including the melodrama between genre cinema and public health discourse; the form of melodrama itself with DFO’s use of gesture, anguish, and queer life; and responses to the film that demonstrate “feeling backward,” defined as “a gesture that refuses to cling to an unrelenting and unaccommodating optimism affiliated with progress.”

Malakaj reveals the extent to which Hirschfeld’s involvement with the film was politically significant. Founder in 1897 of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, a campaign for the social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, and against their legal persecution, the sexologist regarded DFO as a vehicle to help promote his new Institute for Sexual Research, which was opening in Berlin shortly after the film’s launch.

As well as co-authoring the script, Hirschfeld appears several times in the film as a fictional version of himself. The most critical is a lecture hall scene where he delivers his theory of sexual indeterminacy and homosexuality, a presentation Körner is seen viewing from the back. Here, writes Malakaj, “the hopeful tenor affiliated with the lecture and its impact on Else collides with Körner’s worries, generating a tension that persists throughout the film between affirmative politics and the pain of living life as a homosexual in a hostile world.”

Hirschfeld’s final appearance provides a didactic moment for the film’s ending, depicted only in photographs. Imploring the grieving young Sivers not to copycat his late lover by committing suicide, the sexologist encourages him to instead survive and dedicate himself to making life better for all queer people by fighting to have Paragraph 175 rescinded.

*

Malakaj takes issue with some aspects of post-Stonewall queer analysis of DFO, including that by Vito Russo in The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies (1981). Russo regarded Körner’s death at the end of the film as “an obligatory suicide,” the assumption being that filmic treatment of gay men is intrinsically homophobic so they must inevitably “suffer for their sexuality.” While sharing Russo’s insistence that queer viewers are deeply affected by cinematic representation, he pushes back against such totalizing claims by noting that mournful imagery can be generative as well as limiting. “Feeling bad with others is part of life,” he notes. “Cinema—in particular melodrama—affords us an opportunity to do so.”

Given efforts by conservative society to erase it from history, both during the Weimar period and during Nazi rule, the author rightly regards DFO’s survival as nearly miraculous and a tribute to the liberatory spirit of its creators. Malakaj recalls how, shortly after its release, DFO was banned from public screenings and Germany’s censorship law was soon reinstated. When the Nazis came to power, they nearly succeeded in destroying it: DFO was reduced to less than half its original running time.

Happily, notes Malakaj, two restoration projects took the remaining footage and supplemented it with subtitles and photographs based on archival material, increasing the running time to fifty-one minutes. Rather than trying to recreate viewer experience of the 1919 original—an impossible goal, given how much of the footage was lost—the added context in both new versions of the film not only helps us “ponder the gaps between authentic footage and restoration material, but also stimulate viewers’ imagination of past queer life.”

Knowing what will become of Hirschfeld and his institute once the Nazis take power, contemporary viewers experience a sense of doom and foreboding while watching DFO. Malakaj recalls a similar effect from a queer history tour of Berlin on the hundredth anniversary of the film’s release. Meeting at the former site of the famous sexologist’s institute, he recalls, “meant activating for the attendees of the commemoration feelings affiliated with queer potential” (the exceptional venue for research and advocacy that Hirschfeld and his collaborators had nurtured) “and queer injury” (the historical violence that doomed the institute).

*

Admirably, Malakaj does not attempt to employ DFO as a marker for progress in queer rights. As he notes, the film is “deeply entwined with bad feelings” thanks to “its impossible love story, its painful ending…and the burdened history of censorship, transmutation and migration,” so his response to the film avoids what he regards as homonormative uplift.

Instead, he regards DFO as an exemplar of the queer cinema of mourning, which demonstrates how cinematic negativity need not be exclusively anti-social or devoid of sustenance. On the contrary: as viewers, we can identify with Körner’s struggle because it reminds us that our own experience is “linked to a history of struggle that reaches from the past and into [our] present and will pattern the future.”

Malakaj is a most effective guide in taking us on that journey, thanks to this fascinating and highly readable take on a ground-breaking film from the silent era.

[Editor’s Note: Any readers curious to see the original 1919 film Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others) can find it at this YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OucCEjlMNbk]

*

Daniel Gawthrop is the author of the novel Double Karma (Cormorant) and five non-fiction titles including The Rice Queen Diaries (Arsenal Pulp Press). Visit his Substack here and his website here. [Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has recently reviewed books by David Geselbracht, Maureen Palmer, Brian Antonson, Harman Burns, Ed Willes, and Billy-Ray Belcourt for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster