Tested solutions from climate optimist

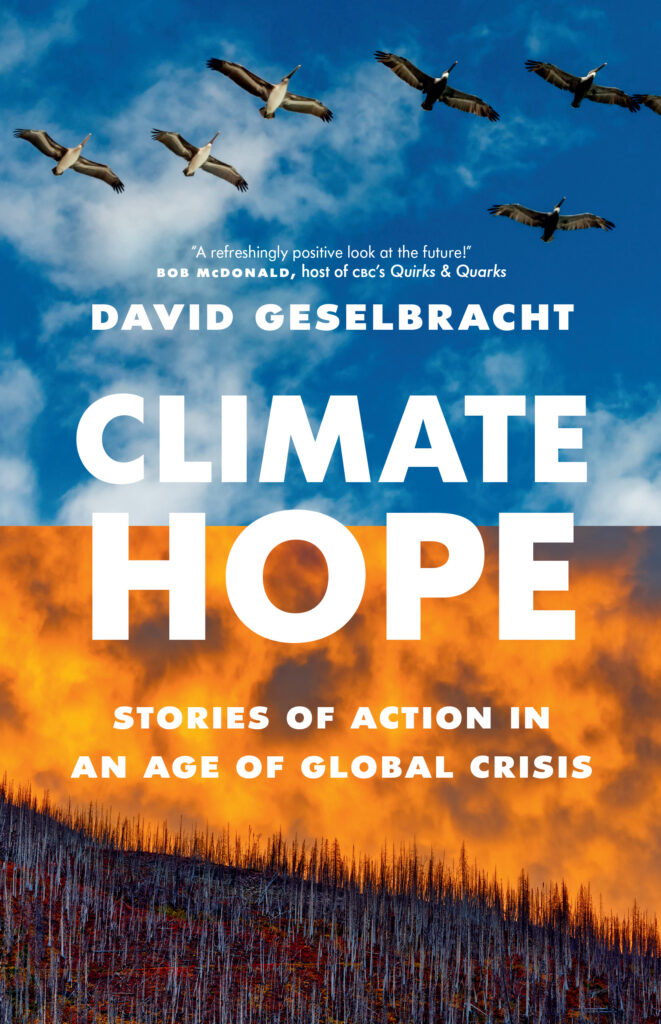

Climate Hope: Stories of Action in an Age of Global Crisis

by David Geselbracht

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2024

$24.95 / 9781771624268

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

Books about climate change can be pretty depressing. I recall suffering weeks of existential angst after reading David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming (2019). That book described, in gruesome detail, the harsh reality in store for hundreds of millions of people living in the planet’s hottest zones over the coming decades. Thankfully, Climate Hope offers some relief from the cynicism and despair of confronting global warming.

This book was launched a couple of weeks before the U.S. election, when climate science was already under attack from the fossil fuel industry and other reactionary forces. With Donald Trump’s return to power, and his populist enablers hell-bent on scrapping the Environmental Protection Act, the optimism of Climate Hope might seem a hard sell for some readers. But David Geselbracht, an environmental journalist and lawyer from Nanaimo who has written for Canadian Geographic and The Globe and Mail, has no time for climate denialism. Instead, he’s out to prove that climate action around the globe is making a difference; that there’s been progress in the effort to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and slow the planet’s warming.

Climate Hope begins with the story of Mary Vaux, the 19th century glacier explorer who became obsessed with a giant piece of ice in B.C.’s Selkirk Mountains. Charting the Illecilleawaet glacier’s non-stop contraction over nearly a quarter of a century, Vaux produced the first formal glacier study in Canada.

“Driven by curiosity, a passion for the outdoors and a belief that scientific observation of the natural world mattered,” writes Geselbracht, “her work offers a window into the past…[and] a bridge to the present, where climate change has shifted our understanding of glaciers and their critical yet vanishing place in the world.”

The author’s take on fossil fuels is more nuanced than that of many eco-activists. He acknowledges, for example, the economic importance of fossil fuels in providing about 80 per cent of the world’s primary energy. The problem is over-reliance and its consequences: the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations that oil and other fossil fuels create have increased global warming, leading to extreme weather events like the 2021 “heat dome” that killed 619 British Columbians. From Charles Dickens’s Bleak House to a Harvard study revealing that more than eight million people died in 2018 from breathing air containing their particles, the “glaring downsides” of fossil fuels make the case for the solutions explored in the rest of the book.

A chapter on climate evacuees recalls the 2021 wildfires in B.C. that destroyed Lytton and threatened other neighbouring First Nations communities like Kanaka Bar. Here, climate action is about common sense preparation and prevention. Thanks to that disaster, local communities are developing climate monitoring systems that include stream gauges to monitor seasonal river flow, temperature monitors, and even air quality monitors to assess when smoke from incoming fires is becoming too dangerous. “FireSmart” methods include cutting down trees that are too close together, clearing the land of fallen branches and other debris, building new reservoirs to increase stored water, and providing more hoses, hydrants, and sprinklers.

Adaptation is a key theme. “Rather than acceptance, adaptation is about action,” says Geselbracht. “It’s about preparing for what is and what will continue to be—warmer weather, higher precipitation, and the myriad ways these intersect and intensify to impact the communities most at risk.”

Climate action also takes place in the courts. Geselbracht notes how the number of climate change lawsuits has rapidly increased over the past two decades: from three cases in two countries in 2001 to 884 cases in 24 countries by 2017. Over the next five years, climate cases more than doubled while spreading to more than 40 countries. In the U.S., we can expect those case numbers to rise even more under the Trump administration.

In Canada, the Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that the federal carbon tax is constitutional. This decision affirmed the urgency of tackling climate change, which the presiding chief justice called “a threat of the highest order.” Geselbracht, summing up the decision’s impact, says that Canada’s highest court had confirmed that climate change demands collective action: “Cases like this show that every country needs to pitch in, corporations will be scrutinized, and courtrooms can act as forums of climate accountability.”

From here, the book moves on to explore fossil fuel alternatives that have already proven effective.

In the chapter on electric vehicles (EVs), Geselbracht drives a rented Tesla from Toronto to Quebec City to demonstrate the EV’s safety, cost effectiveness, and—most importantly—eco-friendliness. Although the production of their lithium batteries emits carbon dioxide, EVs cut emissions by 69 per cent more than combustion engine vehicles. But the savings are most impressive: by the time he reaches Quebec City, Geselbracht has travelled 800 kilometres and spent $30.86 on electricity—less than a third of what he’d have spent on gas.

At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, he meets Scottish Trade Union Congress general secretary Roz Foyer, who advocates for new jobs in the emerging green economy. (A “just transition,” says Foyer, should include new opportunities for workers—such as a government plan to retrofit old buildings to make them more energy efficient.) He also attends the People’s COP, a protest where no-nonsense youth activists (“Don’t COP out!”, “No more Blah Blah Blah,” their placards read) demand firm commitments to change—not lip service—from world leaders.

“Archimedes Revived” looks at solar energy. In the decade after 2009, the price of solar energy dropped by 89 per cent, making it highly competitive. As fossil fuel usage decreases with scarcity, notes Geselbracht, solar will become an important alternative. It all began in 1913, he recalls, with the dramatic unveiling on the banks of the Nile (“where Egyptians once worshipped Ra, the sun god”) of American inventor and engineer Frank Shuman’s first solar engine. This “massive machine” comprised “five crescent-shaped reflectors, each over the length of an NHL hockey rink and lying in parallel,” the boiling water and steam generated capable of “power[ing] a 55-horsepower engine, enough to pump 6,000 gallons of water a minute from the Nile. The implications were enormous. Rather than using expensive coal to run water pumps, solar energy could help irrigate vast croplands for much cheaper.”

In the chapter on atomic energy, Geselbracht takes on a sacred cow of the anti-nuke peace movement of the 1970s and ‘80s. Travelling to Stockholm, he learns that Sweden’s energy mix is almost 100 per cent fossil fuel-free: decarbonized electricity through a mix of nuclear, hydro, and “a bit of wind.” Visiting a nuclear power plant, the author describes how electricity is created through a chain reaction called fission, which generates thermal heat that creates electricity through boiled water turned into steam.

Despite public wariness due to memories of Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima, peer-reviewed research confirms that nuclear energy is one of the safest forms of electricity—even safer than wind and solar. And it’s efficient. “A nuclear plant can run for a year on a truck’s worth of uranium fuel,” notes Geselbracht, “while a coal plant of the same size would require 25,000 railway cars.” Nuclear plants may be expensive to build and maintain, but South Korea has standardized models that help to build lower-cost and emissions-free nuclear power plants.

Climate Hope takes a curious turn with its look at Christian environmentalism. Here the author examines how the meaning of “evangelical” has been appropriated from its traditional roots by right-wing American populists who see eco-activism as a form of godless communism. (Such Christians, notes Geselbracht, “take the Bible more literally than most; yet they haven’t always been as serious about protecting what God made.”) While his overall point is well taken—progressive Christians can indeed increase youth engagement by nurturing a sense of hope through action—the role of religion in responding to climate change seems a subject for a different book, and one that includes a range of religions.

Geselbracht is most convincing when exploring the practical realities of climate action. Most revealing is his visit to Copenhagen in Chapter Eleven. At the CopenHill waste incinerator, located below the ski hill and café he visits, the author describes how the city’s waste is converted into energy that warms 98 per cent of Copenhagen’s homes. But Denmark’s capital and largest city is having a crisis of conscience: it will not reach its goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2025—a target, set in 2012, that the author notes “is the most ambitious net-zero target of any city in the world.”

It’s hard to learn of such self-criticism without contemplating the absence of similar civic accountability in North American cities. This is a jurisdiction, after all, that saw a 72.5-per-cent reduction in carbon emissions between 2005 and 2021, mostly through increased wind production and transitioning from coal- and gas-powered incinerators to those that burn refuse and biomass. An outstanding achievement by any measure—but not quite enough for Kirstine Lund Christiansen, author of a critical report on the city’s failure to reach its target.

Geselbracht praises locals like Christiansen for taking their important role as citizens so seriously: “to thoughtfully criticize and to question the direction of their own city…without disparaging the incredible work that, indeed, had occurred in Copenhagen.”

These and other inspiring stories Geselbracht shares remind us how the impacts of global warming can be mitigated or reduced—if not reversed—through collective and individual action. Unlike the doomsayers who seem to have given up, he sees the glass as half full. This alone makes Climate Hope a decent and worthy undertaking, as well as a good read.

*

Daniel Gawthrop addressed climate change issues in his third book, Vanishing Halo: Saving the Boreal Forest (Greystone/The David Suzuki Foundation). He’s also the author of the novel Double Karma (Cormorant) and four other non-fiction titles including The Rice Queen Diaries (Arsenal Pulp Press). Visit his Substack here and website here. [Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has recently reviewed books by Maureen Palmer, Brian Antonson, Harman Burns, Ed Willes, Billy-Ray Belcourt, and Yeji Y. Ham for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Tested solutions from climate optimist”