Values motivating human rights advocacy

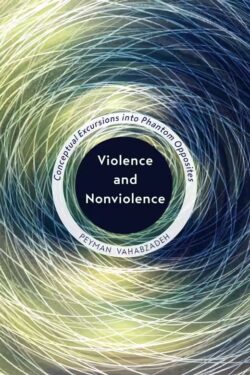

For Land and Culture: The Grassroots Council Movement of Turkmens in Iran, 1979-1980

by Peyman Vahabzadeh

Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2024

$32 / 9781773636658

Reviewed by Linda Rogers

*

Peyman Vahabzadeh comes from a variegated culture of many vines that have flourished in exquisite art, global conquest, and poetic philosophy. Out of that diversity has come harmony and conflict, the exaltation and repression of our finest creative instincts. The brief phenomenon this thesis investigates is one flare of resistance to the powerful clerical movement that took over the many countries known as Iran in the closing years of the twentieth century. Quiet resistance came from a council of Turkmen whose ideology was equality, and they were silenced. It is this author’s aim to resurrect the conversation.

In his book, an examination of the origin and influence of a brief social uprising in the context of an international movement to define the nature of belonging to land and culture, the scholar/author provides a logical blueprint for his own examination of a limited but significant moment in the recent history of Iran, so that the equally confused reader might better understand the deep meaning of protest and need to embrace our commonality.

To this end, he compartmentalizes aspects of the Turkmens’ struggle into aspects of revolutionary thought which are, in the end, based on the same values that have motivated human rights advocates from Jesus to Marx. His philosophical mother star is Hannah Arendt who articulated human plurality as the phenomenal aspect of ephemeral beings. We come and go, and the land is constant.

The first premise is that Iran, like the Earth, is populated by a plurality, multilingual, multiethnic, multicultural, and what unites the Turkmen to others of their ilk is the common belief that the Earth belongs to everyone at once and no one in particular. This makes the short history of their movement, smothered by the black clerical robe that covered all dissent in Iran following the downfall of the Americentric Pahlevi regime in 1979, a universal surrogate for worldwide Indigenous land-based protest.

Vahabzadeh, an urban Iranian until his emigration to the West Coast of Canada, where he teaches at the University of Victoria, is clear from the beginning. His perspective is scholarly and humane. He is sympathetic to the concept of universal human rights and the maintenance of particular cultures, markers for Indigenous peoples, but he is still seeking, as are his audience, to understand the quest for freedom within the context of serial totalitarianism, albeit lacking one important tool.

He neither reads nor speaks the Turkmen language, and that defines an outsider point of view. A speaker of European and Persian languages, he examines available data with a handicap, which makes his readers sympathetic co-learners as they sort through his evidence.

Language, international Indigenous advocates insist, is essential to the understanding of culture, and its denial, as in the case of North American suppression of human rights, negates the ability to own past and present in our phenomenal lives. Still, through dedicated scholarship, he perseveres, taking us with him on his investigation of meaning and intent.

Revolution is about power, but, in almost every moment, the impetus to decency bows to the power of currency. The advent of International Capitalism has changed the odds seriously, with religion playing an outrageous part in the control of human settlement. What this book makes clear, sorting through the rubble of a failed experiment in land and culture, is that the light of decency is never extinguished by ephemeral mind control of regimes and religions. We are better than that.

The Turkmen have language and culture. Integrity is the card they will play in the ongoing transformation of world geography.

They were brutally suppressed by the clerical regime that took over the minds and bodies of diverse countrymen, Muslims, Jews, Ba’hai, and Christians of many faiths and tongues, and fundamentalist clerics will very likely see their own time of eclipse as Iranians continue to insist on reasonable autonomy so that their deep and ancient beliefs and social practice can flourish in every aspect of human excellence, unity in diversity based on the credo, to each according to their need.

Arendt’s is an organic thesis and organisms evolve slowly, without the power bases of money and repressive hierarchies. The author investigates developing council systems around the world: the Mayan Zapatistas, The Syrian Rojavas et al and discovers the possibilities denied to Turkmen caught in the spread jaws of totalitarian monarchy and religion.

There is a terrible loneliness in totalitarian states, from the top down, and basic human needs are never met, as everyone lives in the fear associated with power, haves and have nots, because the mighty fall too. And then the mandate is to begin anew, each newborn promise of better times, a better life, contracts rarely met but always aspired to.

The Iranian diaspora is evidence of the degree of social dislocation brought into play by Iran’s colonial past and clerical present. When rational discourse is suppressed, social contracts wither. He finds global evidence for this.

A friend visiting today reminded me of the erasure of humans and human collectives when I asked what he knew about the Turkman Council Movement, silenced like the young people who secretly listened to heavy metal and recorded bone music on discarded X-Ray plates in the latter part of the twentieth century and the disappeared in Chile. “My friend’s brother left the lab in Tehran where he was researching for his PhD in chemistry and never arrived home to his family. That was 1979 and there has still been no word, not one. He literally vanished, with no closure, a promising young scholar who perhaps was reported for making a remark that was critical of the new regime.”

The Earth moves and with it there is change, new life and constant conversation as the word passes root to root, even in different languages as the author of this book discovered. These roots are as connected as the warp and woof of rugs woven by the Turkmen women who were gaining a voice in the councils that may still change the course of life in Iran, where women have been silenced for almost half a century after making some progress in the time between the Pahlavi dynasty and the Islamic revolution.

There is a common language, a common solidarity the author believes, among the roots people who maintain their connection to the ancestry of land and that blesses the participants in the Turkmen councils “dignity, an alternative collective life, while giving the rest of the country a vision of a better Iran.”

“Viewed from our present-day standpoint in this colonial and rapidly declining world, the Turkmen Council Movement was one of our possible global futures.”

This book presents the possibility for life saving dialogue as the Earth labours under the devastation of failed ideas. May we not wait too long thanks to witnesses like its’ author.

*

Linda Rogers, a Canadian People’s Poet, is currently completing a memoir of Chief Tony Hunt, an artist whose triumph and tragedy were the threshold of reconciliation. [Editor’s note: Linda has reviewed books by Michael Elcock, Marion McKinnon Crook, Tim Schouls, Michelle Good, Marilyn Bowering, and Taro Zion Joy for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Values motivating human rights advocacy”