‘A relationship with place’

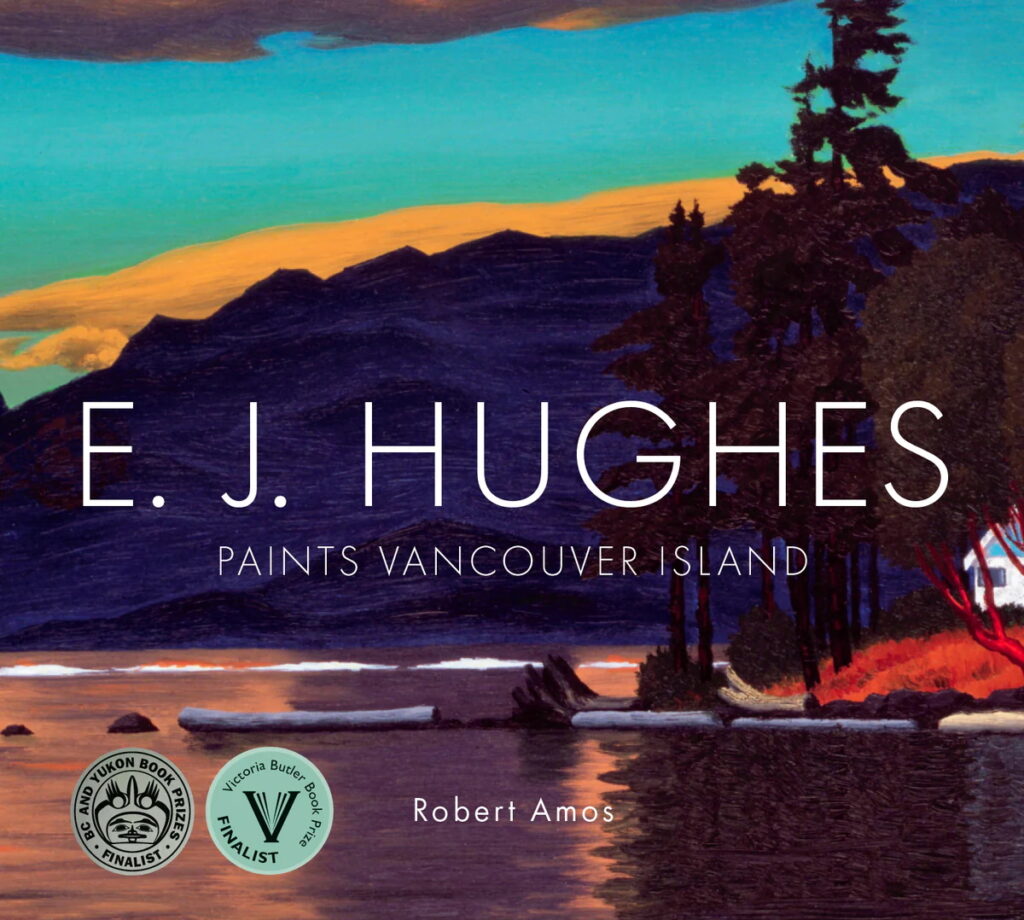

E. J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island (new edition)

by Robert Amos

Victoria: Touchwood Editions, 2024

$30 / 9781771514248

E.J. Hughes: Life at the Lake

by Robert Amos

Victoria: Touchwood Editions, 2023

$25 / 9781771514194

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

While Vancouver Island has some history of having its romantic scenery being captured in the visual arts, its artistic heritage is a rather mixed bag. While much more famous representations exist, it is rare to find more authentic depictions than the paintings of E.J Hughes. Emily Carr is probably its more famous artistic champion; she made iconic the darkly colourful elements of the west coast’s rainforests. In film and television, the Island has been featured to less regard, though still a common location useful for its shadowy and fantastical environment (and its incentivizing tax credits). Indeed, these wooded coasts have featured in such landmark films as Twilight: New Moon, The 13th Warrior, Sonic the Hedgehog, and Scary Movie. The more Anglican refinement of Greater Victoria, meanwhile, has indicated wealth and civility in big screen hits like White Chicks and the X-Men franchise.

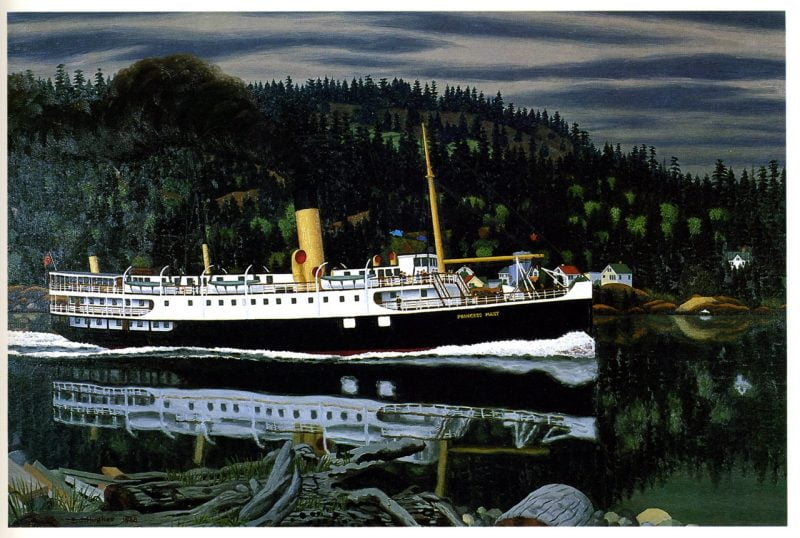

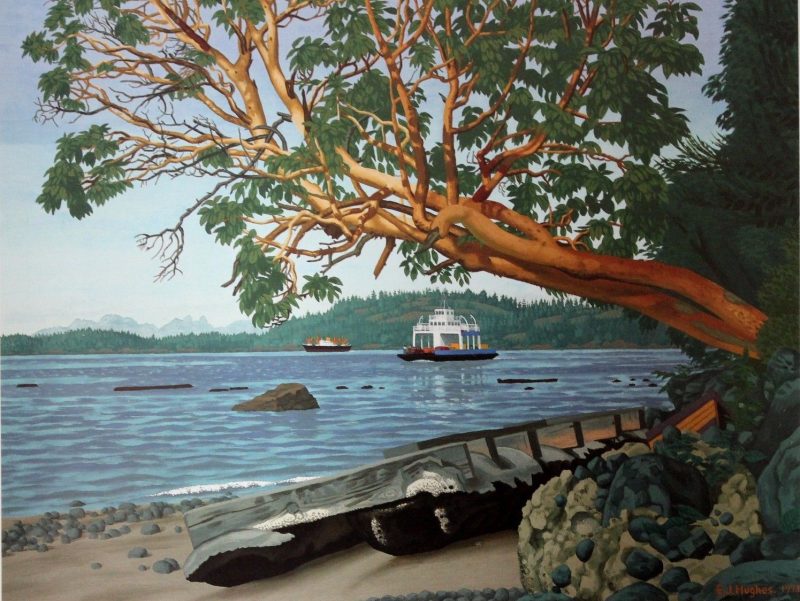

To those of us who have had to make the drive the length of the Island Highway more than once, fantasy is often less apt than monotony in describing this geography. Admittedly beautiful locations – coastal wonders like San Josef Bay and Botanical Beach, or ancient forests like Cathedral Grove and Carmanah Walbran – are separated by hundreds of kilometres of claustrophobic walls of bush, industrial parks, labyrinthian suburbs, and clear-cut logging sites that transport the imagination to a version of Isengard without any towers or adequate military spending. I would less like to indicate any sort of an anti-development political position than communicate a level of cynicism directed towards the local geographical romanticism rooted in a casual and passing resemblance between Vancouver Island and the states of the Pacific Northwest, upstate New York, and medieval Scandinavia. The enticement of E.J. Hughes’ paintings is that, rather than representing an isolated, historical, and detached sense of B.C., they are firmly rooted in their time, romanticizing the mundane and elevating the suburban.

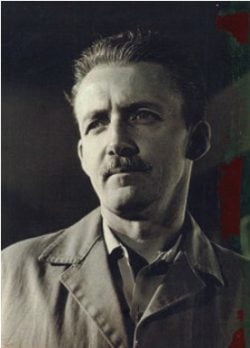

These two of the author’s pentalogy of topically focused biographies of one of British Columbia’s most prolific painters, Robert Amos’ E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island and E.J. Hughes: Life at the Lake, are engaging and intimate looks at the home life and local foci of the famously reclusive artist. Both highlight Hughes’ ability to capture striking beauty in both the romantic and mundane visions of this island. Paints Vancouver Island, a nicely curated collection of paintings and sketches, displays the wild windswept isolation of Bamfield alongside the quiet comfort of North Cowichan’s suburbs. With its focus primarily around Hughes’ decades spent living at Shawnigan Lake and around the Cowichan Valley, Life at the Lake explores the source of the bucolic clarity that Hughes was able to translate onto the canvas. Having written about Hughes’ experience as an army artist during the Second World War, as well as of his professional life more generally, Amos now turns his gaze to the domestic inspirations behind his subject’s most personal works. While the Second World War and Hughes’ professional exploits make their due appearances Life at the Lake, they are seen through a lens orientated around domestic relationships and aspirations.

Amos connects Hughes’ reflective style of painting to his personal association with place in a way that illuminates man, art, and location to the reader. While it may be tempting to impose a view of the rural artist as a Salingeresque recluse, Amos communicates the degree to which Hughes held simultaneously the impulse of a homebody and an appreciation for the exploration of new scenery. This is illustrated in Hughes’ willingness to travel throughout Vancouver Island’s rural extremities and the winding waterways of the northern coastline, as well as a cross-country expedition, despite a propensity to seasickness and a desire to remain removed from the promotion of his work. Hughes’ particular connection to his home at the lake comes less from a desire to be alone, deriving the production of art internally from innate imagination, than a true appreciation of the relationship one can have with the natural world through a relationship with place. Amos expertly displays this ethos with a quote by Hughes in one of his rare appearances on film for the CBC:

I paint Nature matter-of-factly. It feels much better to me to think that an artist is working more to show his appreciation of what already has been created than creating things himself… I think Nature’s so wonderful that I want to try to get my feeling down about that on canvas if possible. I feel that… my painting is a form of worship.

Professedly, there is no hidden meaning essential to understanding Hughes’ work. In all that Amos writes of the man and his oeuvre, one gets the sense that at its core the main principle is simple appreciation. This allows Hughes to elevate his scenery in a way that can feel more real than a photograph. There is what is described as a ‘primitive’ and ‘hallucinatory’ affect from Hughes’ work. Fittingly, Crofton – a place known for its large mill and its small ferry terminal as much as its eerie black sand beaches – is what Amos notes to be Hughes’ favourite location to paint. One would think that most artists would focus on the sand, using its uncommon darkness to imitate a primevally romantic geography devoid of human tampering. Hughes, however, includes the cars, the smoke, the randomly sawed driftwood. He brings life to an eternal pause and simply observes. It is the sort of observation that could only come from someone who lived the way that Hughes did.

The shores of Shawnigan Lake, just north of Victoria, are today studded with cottages and private docks, its waters combed over by jet-skis. It is now not nearly as rustic as it was when E.J. Hughes migrated there after having tried his hand at being a landlord in James Bay. The reader sees the artist’s life as one of balance – his comfortable loving relationship with his wife, the constant upkeep duties required on his property, and the constant nagging desire to paint. Hughes is active in pursuing and representing the simplicity of his home when it features in his work. This reflects his painting style, which represents its subject with straightforward accuracy, but is complicated and energised by an idiosyncratic flair of colour that indescribably gives a simple lakeshore spotted by houses personality. Being removed but not remote, titular lake of this book serves to represent Hughes’ position of having one foot in the exclusive art scene, with paintings in the National Gallery, and one foot in the secluded countryside, with his isolated cottage studio.

Amos shows that Shawnigan served not only to emphasise the artist’s position to appreciate nature, but also emphasised his close relationships with select people, without whom Amos would have not had nearly the same amount of personal material for his book. A significant source for these books is Pat Salmon, Hughes’ neighbour, companion, and biographer. Hughes’ ability to enjoy privacy and acclaim simultaneously was due to another important relationship in his life. The artist’s relationship with Max Stern, proprietor of the Dominion Art Gallery of Montreal, was a near perfect outlet for Hughes’ ambitions. Simply put, Stern agreed to buy every piece produced by Hughes. This arrangement illustrates to great effect the priorities that Hughes had in painting – he was not interested in self-promotion, though receptive of success. Hughes’ most constant relationship, more than that of his biographer or his lake, was that of his wife, Fern. Their marriage runs through this book, through Fern’s failing health, which leads a move away from Shawnigan, to her death. In a profession often plagued by the domestic strife of idealistic dreamers, unsatisfied and prone to reject their present state, Amos describes Hughes as an artist who finds the ideal in the real, reflecting equally well on his dedication to his work and personal relationships.

In an age where photography becomes ever increasingly accurate, and where artificial intelligence is progressively able to create new representative images, Amos makes the case that Hughes’ art shows what no machine can capture, what no mechanical creation can translate. Hughes’ paintings strive for accuracy in depicting the artists’ surroundings, and a camera can certainly capture all that; even so, Hughes’ use of colours in emphasizing certain select features act not to simply represent the space, but as a representation of how Hughes saw the space. As Amos describes how Hughes lived in that space, the reader sees even clearer the emotional truths embedded in the geographical truths of the painting. How important the artist is to the art is illustrated in the way Amos aligns Hughes’ domestic life with his artistic creation. There are imperfections in Amos’ books – some photos of certain paintings featured in Paints Vancouver Island are blurry, for instance. However, for all they include these two books are a refreshingly honest representation of an artist who revelled in promulgating the beautiful clarity of personal vision.

Unlike his other books on E.J Hughes, including E.J Hughes Paints British Columbia, The E.J Hughes Book of Boats, and E.J Hughes: War Artist, Life at the Lake is more about the painter, and his home, than it is about his paintings. Paints Vancouver Island, on the other hand, connects the artist to his surroundings by using a carefully selected collection of Hughes’ sketches, paintings, and notes to follow his infrequent trips taken up and down the island he called home. While a book so domestically orientated might not seem as exciting as one about wartime artistry, these entries into Amos’ series of Hughes books is intriguing in the way it zeroes in on its subject and enlightens his work through relating his personal experiences. In this book describing a man ‘worshipping’ his home surroundings through art, Amos accordingly achieves success in building for his reader an appreciation of Vancouver Island for its own sake. Far from the mystery imbued in the works of the Island’s more famous resident artist, Emily Carr, Hughes takes the same scenery and notes the sublimity in its normality. Both Paints Vancouver Island and Life on the Lake, like their subject, portray the person and place as mutually enriching. Taken together they would prove an engaging read for those interested in learning about Hughes’ personality on a deep level, or simply just perusing his most characteristic paintings.

[Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve previously reviewed the 2018 publication of E. J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island, Christina Johnson-Dean reviewed E.J. Hughes: Life at the Lake earlier this year, and Alan Twigg wrote on the subject of E. J. Hughes upon the 2018 release of E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island for The British Columbia Review.]

*

Matthew Vernon Downey is an independent writer and researcher based out of Victoria, B.C.. He has degrees from UVic (BA hons) and the London School of Economics (MSc) [Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also reviewed books by Alan R. Warren, Gregor Craigie, Robert Crossland, Donna (Yoshitake) Wuest with Joe W. Gardner, Mike Whalen, and D.C. Reid, for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “‘A relationship with place’”