Reconceptualisation of our local environments

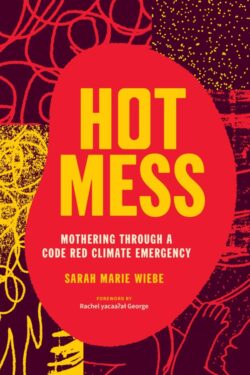

Hot Mess: Mothering Through a Code Red Climate Emergency

by Sarah Marie Wiebe

Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2024

$25 / 9781773635668

Reviewed by Petra Chambers

*

I started Hot Mess: Mothering Through a Code Red Climate Emergency by Sarah Marie Wiebe on an October morning, cozy on my aunt’s couch in East Van. I read most of Hot Mess over the next 28 hours in my car in the middle of an atmospheric river.

It’s a venerable couch. Almost everyone I know has crashed there over the decades—my aunt’s house is a sanctuary and way station for all the people she cares about. I read Rachel yacaaʔał George’s forward and Wiebe’s preface there, while tracking the huge blue-purple-yellow weather app blob advancing toward the coast on my phone.

Hot Mess weaves stories about Wiebe’s rough transition to motherhood in the midst of a series of extreme climate events with her scholarly work about the nature and impacts of eco-emergencies. She looks at the escalating climate crisis head on and offers a structure to help us orient to the enormity of the topic. This compact book is organized in eight colour-coded essays, which Wiebe refers to as vignettes. Each vignette focuses on a different aspect of the mess that is increasingly our new global and local normal.

Hot Mess kept me company as I waited for three different ferries that day, surrounded by rain so fierce my car felt like a submarine. I read the first two vignettes Code Red: Feminist Motherhood in a World on Fire and Code Orange: Cultivating Community through Disasters on the Queen of Coquitlam, which swayed as it left the shelter of Horseshoe Bay. From Nanaimo, I hydroplaned north, trying to outrun the ‘extreme’ yellow centre of the weather-app blob that was now almost directly overhead. I read Code Pink: A Splash and Dash Caesarean and Code Blue: Living through Multiple Crises, Climate Anxiety, and Mental Health in hammering rain at Buckley Bay, waiting for a storm-blown fishboat to be disentangled from the cable ferry. After several hours, I advanced one more space on the climate emergency gameboard to Gravelly Bay, where I read Code Green: Circular Economies of Care and Code Black: Systemic Threats, Revealing Violences Slow and Spectacular in my tin-can terrarium of a car.

The irony of contributing to future extreme weather events by driving a fossil-fuel-powered vehicle wasn’t lost on me. And yet my car was my shelter from the storm. To me, this highlights the challenge of our current era, and the conceptual difficulties we have with cause and effect, given the far-flung geographic and temporal consequences of our individual and collective actions. This challenge is exactly what Wiebe grapples with in Hot Mess.

My place in line was under a streetlight, so I kept reading into the tempestuous night, finishing Code Grey: A Cautionary Tale of Renewable Extraction, still half-heartedly waiting for a break in the storm and a ferry that never arrived.

When the power went out, I tried to get some sleep.

The following morning, chilled and thirsty, I read the final chapter Prismatic Reflections: Cultivating Care and Community through Multifaceted Crises.

Climate change impacts human life on all levels; we feel its effects as individuals, families, communities, and nations. As Wiebe notes, these effects unfold within staggered and discordant timeframes: unfolding both quickly and slowly. Climate events affect all life on a global scale. It’s overwhelming. Ecological grief can be debilitating. Caroline Hickman developed a conceptual framework for eco-anxiety that describes a range of impacts from mild to severe. At the far end of the spectrum, Hickman list symptoms that are incapacitating, including terror, inability to maintain employment, and suicidal ideation.

Writers who wade into this space need to figure out how to communicate without causing readers to either fall apart or tune out. The emergency codes used as an organizing structure in Hot Mess are Wiebe’s elegant solution. The codes enable us to navigate the complexity of this topic, as does the inclusion of Weibe’s first-hand experience as a new mother. She explains that the “boundaries between the personal, professional, and planetary aspects of life are collapsing” and she models this by bringing the messiness of her personal journey into her work as an ecofeminist scholar. This personal-transpersonal blend of perspectives is what makes this book so impactful.

Wiebe writes about stuff I quietly obsess over: viable alternatives to our current patterns of thinking and living that are contributing to the climate emergency. She offers examples, including traditional Indigenous land and community structures, circular economies, and concepts like ‘earth democracy.’ Obviously, there are no easy answers. Wholeheartedly engaging with this intractable problem is a first step, and seriously considering alternative lifeways is a second. As I read, I noticed a longing to discuss aspects of Hot Mess with others (and not only because I was alone in a cold damp car). I imagined a book club that would discuss one colour-coded chapter at a time, supporting each other with any emotion that may arise and focusing on the more invigorating and hopeful work of envisioning realistic sustainable futures and making concrete changes.

The storm abated and the ferry finally made it across the Lambert Channel late the following morning. After getting home, rehydrating, slowly warming up, and sleeping I had a video chat with Wiebe. I was curious about how she came up with the codes as a way to organize such complex content. She told me that Code Red was obvious, given that United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres declared a “code red for humanity” in 2021, the year that she had the perinatal experiences that led to Hot Mess. Wiebe was in and out of hospital with her newborn baby numerous times that year, due to health issues related to extreme weather events, including the unprecedented heat dome that scorched all of us and killed billions of sea creatures that June. She explained that she started noticing the colour codes during her repeated visits to the ER that year: Code Orange for mass casualties; Code Pink for pediatric and obstetric emergencies; Code Grey for system failure. She borrowed these codes, expanding the meaning of some, as a way to organize the material she wanted to explore. I think this approach really works.

Fernwood Press is an academic publisher and Wiebe said that the tone of the book strayed further in a scholarly direction than she’d originally intended. She wanted Hot Mess to be accessible, and I think she succeeded. She assumes her readers are intelligent and capable of grappling with the facts. Her writing is clear, and blends research with her personal experience, which makes the vignettes very readable, both intellectually and emotionally.

This is an important consideration for a book that is intended to be an intervention. Wiebe and I discussed the call to action that this book makes: a reorientation to an ethic of care as an alternative to a society based on extraction and materialism.

In Hot Mess, Wiebe asks “what does it take to reconceptualise how we look at our local environments, viewing them as sites of care, love, connection, and meaning rather than a sight of extraction?” She says “an ethic of care – love for one’s child, for environments, for communities – may seem simple, but it is also a radical approach. Care is at once deeply personal and profoundly political.”

I’ve been thinking about the identification of care as the alternative organizing force for humanity. Through the unexpected climate-related adventure I had with Hot Mess, my East Van aunt’s welcoming attitude and well-loved couch have become a symbol of this alternative to the extractive capitalistic worldview that got us all into this [too wet/too hot/too stormy/too dry/too scary] mess.

Hot Mess was an excellent companion during my atmospheric river experience. I felt accompanied through that long cold night, and I am aware of how fortunate I am. Four people died on the southwest coast while I was reading: two when the road they were travelling on washed out, one attempting to save a dog that had fallen into a river, and one sheltering in place when her home was swept away.

The consequences of climate change are real and they will affect all of us, sooner or later. If you’re not sure what to do, where to begin, I suggest reading Hot Mess. With a friend.

*

Petra Chambers (she/her) lives in the traditional territory of the Pentlatch people. She writes creative nonfiction, poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms. Her work has been published by PRISM International, Queens Quarterly, The Fiddlehead, CV2, and Prairie Fire, among others. She is the 2024 Yosef Wosk Fellow for the Vancouver Manuscript Intensive. Her first poem was nominated for a 2025 Pushcart Prize. [Editor’s Note: Petra Chambers has recently reviewed the work of RJ McDaniel for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Reconceptualisation of our local environments”