Important contribution to our legal history

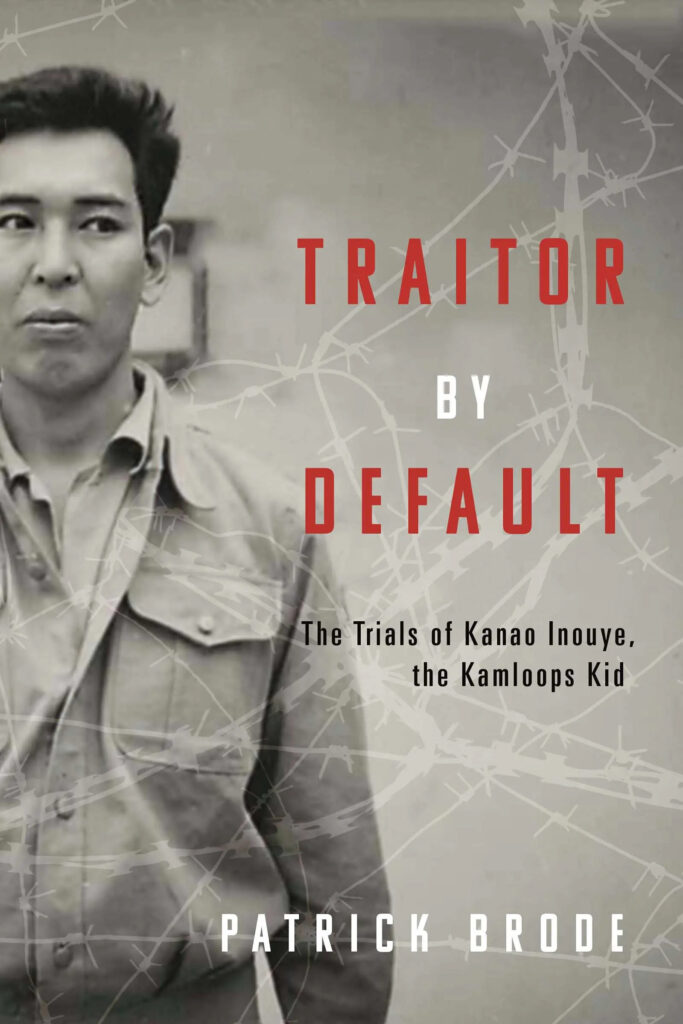

Traitor by Default: The Trials of Kanao Inouye, the Kamloops Kid

by Patrick Brode

Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2024

$26.99 / 9781459753693

Reviewed by Kenneth Favrholdt

*

Patrick Brode suggests the controversy of this case in his title, in this masterful exposition of a little-known story of a Japanese-Canadian sentenced to death for his role in the torture that took place at an infamous prison at the end of the Second World War.

As a respected Canadian lawyer, Brode, author of many books on the history of law, is well-qualified to write on this subject. He presents a detailed account of the trials of Kanao Inouye that makes an important contribution to the legal history of Canada and British Columbia.

Born in Kamloops in 1916, Kanao Inouye had Japanese parents. His name “Kanao” was given to him by his grandfather. When the Great War broke out in 1914, many Japanese Canadians sought to enlist in a volunteer corps. Kanao’s father, Tow Inouye, enlisted in 1916 as a member of the 131st Westminster Battalion. He became a decorated war hero. He later became a successful merchant operating an export-import business.

Kanao’s family visited their ancestral homeland in 1926 but on the trip his father died, leaving Kanao the koshu, or head of the family. When they retuned, Kanao went to trade school in Vancouver. When he finished Kanao travelled back to Japan in 1935 on a Japanese passport and became his grandfather’s ward.

But Kanao Inouye, fluent in English, found it difficult to adjust to Japanese life as a Nisei, or foreign-born Japanese. After Japan went to war with China in 1937 and attacked America at Pearl Harbour in 1941, Inouye found his English-speaking background useful. He was sent to Hong Kong to serve as a civilian interpreter.

Then, in 1942 he became a police interpreter for the Japanese army at Sham Shui Po prisoner of war camp in Kowloon, Hong Kong, where 1,700 Canadian survivors from the Battle of Hong Kong in December, 1941 were incarcerated.

Early on, Inouye got the nickname “The Kamloops Kid” and among the Canadians was known as “Slap-happy Joe” for the abuse meted out by striking prisoners in the face. He was known as a sadistic guard. But his sadism, he argued in his trial, was the product of experiencing racism in Vancouver where he went to school.

During this time back in Canada, the federal government ordered the removal of twenty-two thousand Japanese from the west coast of British Columbia to be dispersed across the country. After the war Inouye was arrested and charged with war crimes.

Brode goes into great detail about Kanao’s relationship with officers and also his victims, who suffered torture by water-boarding and being hanged upside down and beaten. But as Brode asserts, Inouye was not at the centre of all the cruelties in the POW camps. “Inouye did not act on his own initiative, for it was the camp commandant who ordered the punishment.”

Kanao’s first trial had three counts, one for committing a war crime for assaulting a Canadian captain at the Sham Shuipo Camp, the second also for committing a war crime for assaulting a Canadian major, both in view of the Canadian prisoners, and the third relating to the ill-treatment of several civilian residents of Hong Kong.

Inouye’s defence attorney, stated there must be some mistake and that “he should be tried for treason rather than war crimes.”

A second trial was held in April, 1947. The final day of the Supreme Court trial saw only Inouye take the stand in his own defense. Brode recounts his testimony: He stated that, “I have regarded myself as Jap all the time.”

He had acquired a permanent registered address in Japan, at No.7-3 Hongomotomachi, Hongo-ku, in Tokyo. He was too young to know which passport he used to travel to Japan but on the return trip to Canada in 1926, he was issued a Japanese passport. Thereafter, he received a yearly remittance of two thousand to four thousand yen from his grandfather. In September, 1935 he again travelled to Japan with his mother but this time under the 1926 Japanese passport. “I left no home behind me in Canada in 1935… I intended that my home was to be in Japan in the future.”

Inouye found himself perfectly comfortable in the land of his ancestors: “I was treated as if I had lived in Japan all my life. My friends in Japan had no different mentality to friends in Canada.” His studies were interrupted in 1936 when he was obliged to take the military examination… he was then conscripted into the army on March 1, 1937, swearing allegiance to the emperor and proudly adding, “All Japanese subjects have the blood of the Emperor in their veins.”

When Inouye was taken into custody in November, 1946 by the Hong Kong Police, a Japanese document was found on his person which was entered into evidence as Exhibit “C”.

Brode continues: “According to Exhibit C, Inouye was accepted as an A grade candidate for recruitment into the Imperial Japanese Army in June, 1936.” This Exhibit provided an account of Inouye’s service in minute detail – the units he served in as well as his commanding officers. “He ….explained that he willingly served in Japan’s military, and by doing so, felt he was serving his true homeland. Canada was never his country; it was a land of grinding prejudice and discrimination to the extent that he became embittered against all Canadians.”

Citizenship was the key issue. The trial judge asked Inouye if he had inquired into ways of renouncing his Canadian nationality. But in Inouye’s view, he was thoroughly Japanese.

Brode notes that Inouye’s testimony contradicted much of what he had stated earlier. Inouye stated that he “did not appreciate the brutal methods used by the Kempeitai” and that “he acted only as an interpreter and unless ordered to take part in the beatings, took no action of his own.” Inouye, Brode states, denied that he tortured anyone.

Brode has produced a remarkable account of Inouye’s controversial life using a vast range of documents and news accounts. The thirteen chapters head towards a climatic end. What was Inouye’s allegiance?“ Brode states. “On the issue of citizenship, Inouye was apparently Canadian by birth but could not claim Canadian citizenship; however, he also presented significant evidence that his allegiance lay exclusively with Japan.”

In a vain hope of staying his execution, Inouye filed a petition for mercy to the governor of Hong Kong and also wrote an appeal to King George VI of Great Britain.

Brode’s opinion is clear. “While there was no proof that he killed anyone, he was responsible for immense pain and probably long-lasting psychological damage inflicted on many of his victims. For that he unquestionably deserved severe punishment. But as a minor war criminal, Inouye might be expected to receive a prison sentence of five to ten years.” Instead, Inouye was sentenced to death by hanging which took place in Stanley Prison, Hong Kong, on August 26, 1947. It is said he sang a patriotic song “Umi Yukaba” and a final salute to Emperor Hirohito, stating “Tennon Heika Banzai” (Long live the Emperor). Inouye was buried on the Stanley Prison grounds.

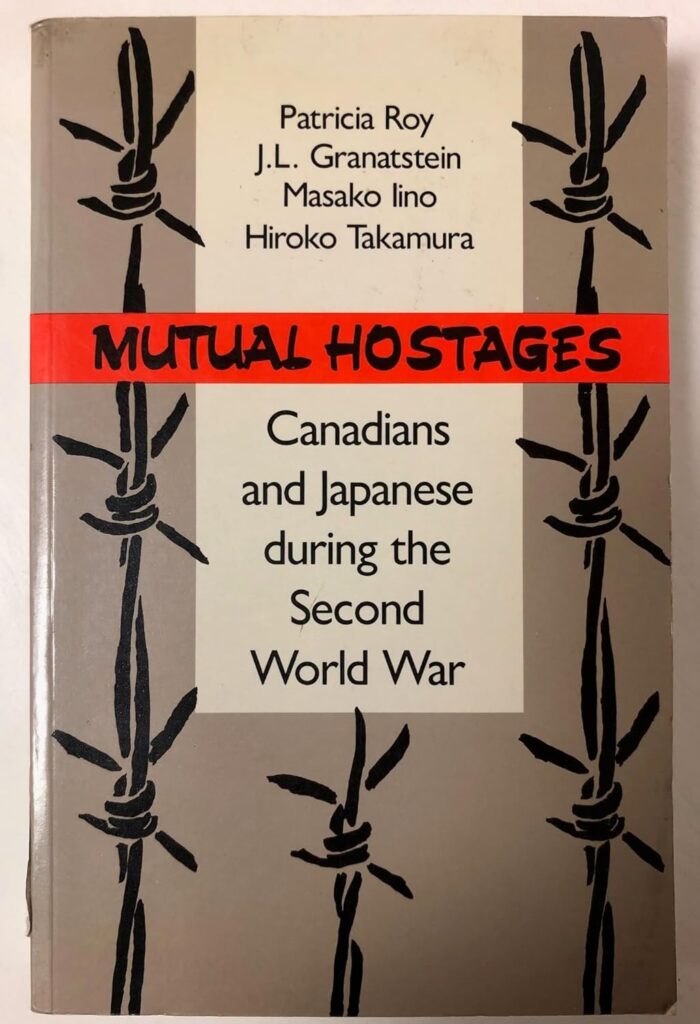

Brode in his closing chapter mentions there have been other renditions of Kanao Inouye’s story including a book, Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese During the Second World War (1990), a documentary by the National Film Board (1991), and a play performed at the Toronto Fringe Festival titled Interrogation: Lives and Times of the Kamloops Kid (2015).

Nobody but Brode, as a lawyer versed in the prosecution of war crimes, could provide such a thorough analysis at this. There are a dozen pages of notes to the chapters, image credits, and an index. Brode has produced a near-flawless book and monument to his profession.

*

Kenneth Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer, and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, four at the Osoyoos Museum, and he is now Archivist of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press, and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartographica, Cartouche, and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and a commemorative history for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken has undertaken research for several Interior First Nations and is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold rush journal of John Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. He lives in Kamloops. [Editor’s note: Kenneth Favrholdt has recently reviewed books by Taiaiake Alfred, Wayne McCrory, Michael Hood & Tom Jenkins, Rueben George with Michael Simpson, Jo Chrona, and Marc G. Stevenson for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Important contribution to our legal history”