Under ‘a low-burning / primordial sky’

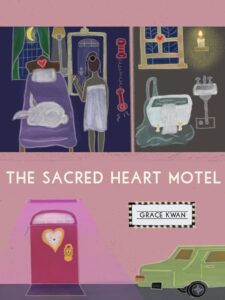

The Sacred Heart Motel

by Grace Kwan

Montreal: Metonymy Press, 2024

$18.95 / 9781998898169

Reviewed by Marguerite Pigeon

*

Grace Kwan has woven several threads through their accomplished first collection, The Sacred Heart Motel. Each is nerve-raw, activating the poems’ ambiguous, sometimes surreal reflections.

Among these threads is the idea of nowhere, or liminality. Kwan divides the book into seven sections; all but one begin with a still-life from the edges of experience. A fire escape, a motel front desk, a room for the night. People may be present there, but Kwan centres the spaces themselves, designed for entry, escape, pause, passage, or labour—never belonging. For example, “Room 209,” which:

features a double bed,

a standing shower,

and a vandalized Bible in the desk drawer.

In “Kitchen: Back Exit,” the reader can practically whiff the hard-won sweat of tired workers on a break:

A row of hairnets, jumpsuits, aprons, blazers,

seen sitting on empty crates with legs crossed,

unaware of one another.

Together, these section-opening poems build a yearning in the reader for what is lasting and, paradoxically, an appreciation for the momentary. In this way, Kwan guides us closer to their poetics: without rejecting confession, the greater concern is with atmosphere, feelings, and the mysteries of an embodied present—possibly our one true home. “or maybe a heart’s // a mystery novel” the poet writes, in “Sacred Heart.”

In embodied time, desire can move freely, musically. The elegant “Intermission” opens with what could be ode to Man Ray’s photo Le violon d’Ingres, blending admiration for a musical instrument and observation of a lover’s body—

Double bass reclined

sidelong in the spotlight

neck bared—

steel tendons belie tender rust. Whose

fingers are so lucky as to smell

of oxidized metal tonight?

Interrupting these immersive scenes, however, is the collection’s second thread: memory. Stark moments from childhood keep arising in The Sacred Heart Motel, bursting into adult life like dissonant notes. They include glimpses of hardship, separate interactions with a mother and father, and formative (presumably strict) Christian and musical training.

Hit by remembrance, the poet is left unbalanced, their space defamiliarized, as in “Lucky Strike,” where a scene of driving in the rain blurs into fantasy when a stranger on the sidewalk becomes the narrator’s father. A collision ensues, followed by a rewind of the action:

You can’t stop the car.

Off the curb, onto the road. Smoke

from his cigarette inhales itself back into

the gathering clump of ash. He passes through the car

or the car passes through him and he backpedals

all the way north to the city in the sky.

In Kwan’s poetic world, time moves in both directions. Memories of the past create intensities of feeling now, and present-day experiences are byproducts of a childhood that was, at times, a space to escape from. In “September,” Kwan evokes a recent experience in a secluded, rainy, region, possibly BC’s Gulf Islands, suggesting that leaving behind religion has been a passageway to beauty and discovery—

What could I have known of life on the coast

—the water the cats the diners the trains

the sunsets and this sweetness—

if not for evangelicalism?

At moments, the intrusion of memory becomes nightmarish, distorting the landscape of the self, as in the poem “Paths”: “and sometimes I see a hole in the shape of me // torn into the fabric of my life, widening // until it’s no longer legible.”

But in this collection, breaches are frequent, not final. The poet is free to experiment with new versions of themself, to revel in choice: “It took me // a while to realize every bad thing // I did went unpunished.” Dissolution, then, is temporary. The very next moment could bring seduction, or at least the potential for good feeling, as in “The Ride”:

Open a newspaper, tilt your head back,

Let sunlight guide your daydream eyes

Over lavender fields

Hurtling past.

This image evokes the final thread in The Sacred Heart: dreams. Vancouver-based Kwan devotes several poems to relating specific dreams. Economical, presented without further comment, Kwan allows dreamscapes to remain at the limits of what language can convey, what memory can hold, like “In One Dream I Dive”:

Forward into milky waves

a red twist of striated muscle

knifing into white

disappearing into purity

under a low-burning

primordial sky.

By letting dreams speak for themselves, Kwan honours the mind as integral, just as lines capturing sensual experience in waking life honour the body’s wholeness. In The Sacred Heart Hotel, this dual, internal sense of belonging is a rallying cry, offering hope that we might all transcend childhood pain and the emotional architecture of alienation.

[Editor’s note: Grace Kwan launches The Sacred Heart Motel on Thursday, November 14, starting at 6:30pm. Details in this link.]

*

Marguerite Pigeon writes poetry, fiction, and reviews. Her latest publication, a book-length poem called The Endless Garment (Wolsak & Wynn), was named to The Globe and Mail’s Top 100 books list for 2021. Originally from Northern Ontario, she lives in Vancouver, where she runs a small editing and writing business, Carrier Communications. [Editor’s note: Marguerite Pigeon’s The Endless Garment is reviewed here by Heidi Greco. Pigeon has reviewed poetry by Matt Rader, Joy Kogawa, Chris Banks, Nicholas Bradley, Cecily Nicholson and Arleen Paré in BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster