Countering the ‘impenetrable wilderness’ narrative

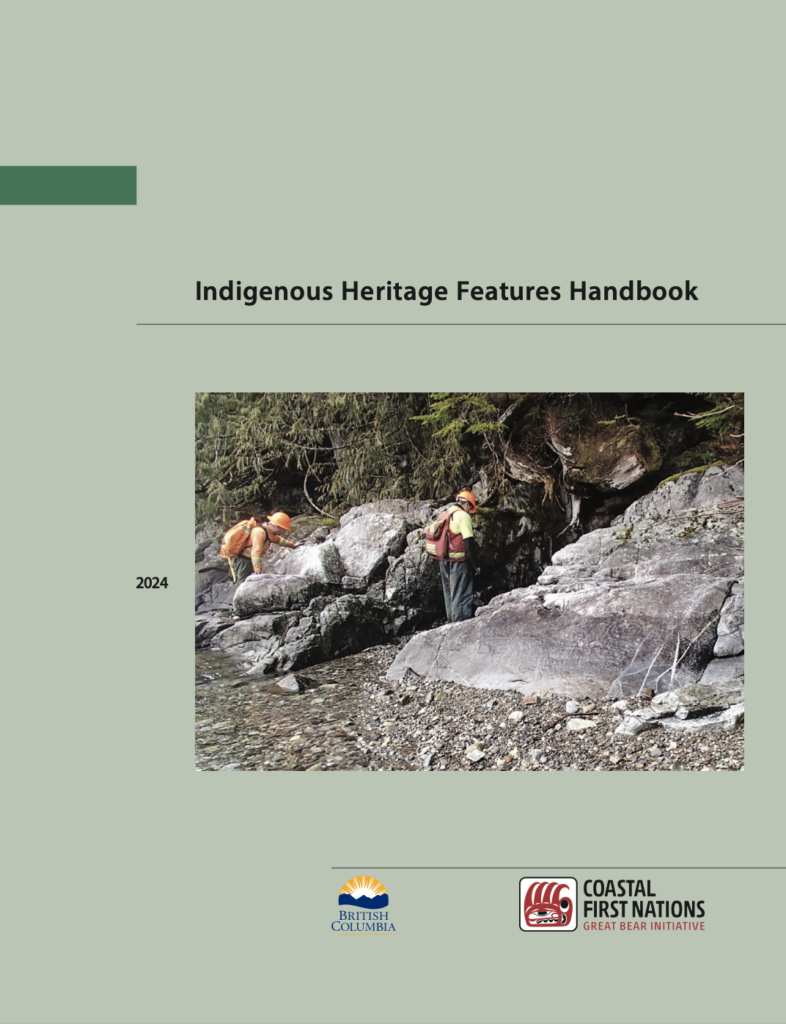

Indigenous Heritage Features Handbook

by Alexander Mackie, Richard Inglis, Qíxitasu (Elroy White), and Kevin Neary

Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative and The Province of British Columbia, 2024

Reviewed by Bryn Letham

*

When introducing myself to new acquaintances as an archaeologist of coastal British Columbia, I am often met with an awkward pause and the question ‘but, what’s there?’ or ‘so, what exactly do you find?’ Frequently, these conversations occur at the pub in Prince Rupert (where I live) looking out on to the Prince Rupert Harbour (where thousands of people have lived for thousands of years), where the shoreline today appears to many an impenetrable wilderness of conifers. Occasionally, questions like those mentioned are from people informed about the Indigenous history of North America and genuinely interested about its archaeology. Sometimes they come from folks surprised that there were people in the region and/or stunned that the people living here before European colonization created or did anything that would be worth studying archaeologically. Often, there is little understanding or appreciation of the true breadth of ways that coastal First Nations modified, managed, and impacted the world around them in tangible ways, never mind the more subtle and less tangible cultural significance impressed upon this world. As infrequently, people lack comprehension of the immense time depth (at least 14,000 years) that people have lived along BC’s coasts.

In some ways, the general public cannot be entirely blamed for their ignorance. Compared with the enduring (i.e., stone) material records of, say, ancient Mesoamerica or Mesopotamia, much of the archaeology of coastal British Columbia is subtle, deeply buried, or poorly preserved. Add to that the fact that archaeologists themselves have only become aware of significant and common archaeological features such as trails, clam gardens, and forest gardens in the last decade or two, one can cut the ignorant lay person a degree of slack. What is clearly needed is more accessible information and documentation of the myriad of ways that coastal Indigenous peoples left their mark on the land and education of how and why the peopled histories of landscapes of the Northwest Coast make these places so culturally significant for First Nations communities today. Additionally, resources for training in the identification and documentation of archaeological features and culturally significant places is necessary. The Indigenous Heritage Features Handbook by A. Mackie et al. makes strides towards addressing these needs through providing a thorough descriptive list of common cultural sites and how to identify them. The text is an accessible reference resource that will be useful to students and budding archaeologists, field technicians working with/for First Nations communities, and any interested visitors travelling through coastal First Nations’ territories.

The Indigenous Heritage Features Handbook is a reference guide to features identified within the 2016 Great Bear Rainforest Land Use Order (GBRLUO); it is designed with the intention of providing “a uniform understanding of the types of Indigenous Heritage Features typically found on the coast of British Columbia, to support engagements between First Nations, Ministry of Forests staff, and industry regarding the protection and stewardship of these features.” Eight Indigenous Heritage Features (ancestral remains, habitation sites, rock art, oral history sites, spiritual sites, harvesting and processing sites, trails, and isolated finds) and their numerous subtypes are each described in detail along with information on where the features are typically found and how to identify them. Examples of almost all the features (except for culturally sensitive ones) are illustrated through multiple colour and black and white photographs and diagrams, often with historical/in-use examples of the features as well as images of the archaeological remnants of older features. Additionally, the text includes several appendices that cover topics such as archaeological dating, geoarchaeology, relative sea level change, and recording rock art. These appendices give the reader contextual background to the methods required for identifying and recording Indigenous Heritage Features.

The content presented is concise and readable, and the illustrations are especially useful (if anything, a resource like this could benefit from even more illustrative examples, perhaps available as an online supplement that could be added to over time). Much of the text reads as a list of a notes converted to full-sentence prose, which makes it useful for a case-by-case identification of features, but maybe not so much for a pleasure read (see readership, below). The coverage is thorough, and save for a few puzzling interpretations (under a discussion of isolated finds, the authors state that in a rockshelter context, “a stone knife might be more likely to be associated with a habitation site, whereas a basketry mat fragment is more likely to be associated with a burial setting”), the information presented should help field technicians make accurate identifications of the Indigenous Heritage Features.

Significantly, the GBRLUO recognizes and advocates for the protection of a broader suite of features than are protected under British Columbia’s Provincial legislation, the Heritage Conservation Act. These include locations with potentially less tangible material remains (the defining requirement of ‘classic’ archaeological sites), such as locations referenced in oral histories, locations known to have been occupied by spiritually powerful entities, and areas known to have been important zones for resource harvesting. It also requires more generous protective buffers for Indigenous Heritage Features in the face of industry and development. This expansion of the scope of what constitutes a ‘site’ effectively enforces an argument for a more fulsome recognition of the significance of the more subtle features that compose a broader cultural landscape. This approach better represents Indigenous worldviews and values, and sets a standard for increasing that appreciation more broadly.

The overall readership of the Indigenous Heritage Features Handbook may be a bit limited by the scope of its content and its presentation, though it will be useful for its proposed purpose. Most of the handbook is primarily a reference guide, and as such would not make compelling cover-to-cover reading. As such, its main strength will be in its intended use: as a field guide for industry technicians and First Nations monitors working on the land. Additionally, the handbook would be immensely useful in field training courses and entry-level college or university courses. I teach both intensive field skills courses for Coastal Guardian Watchmen and first- and second-year anthropology/archaeology courses at Coast Mountain College in Prince Rupert, and the Indigenous Heritage Features Handbook will be a welcome required resource for students in those classes. Furthermore, I could see copies of this text being of interest to other people working/traveling on the coast of BC. Recreational visitors would find the text useful for recognizing how the ‘impenetrable wilderness’ of BC’s shorelines is actually a cultural landscape shaped by thousands of years of human presence, occupation, and management.

The handbook could be made more broadly useful by being more comprehensive. Some of the most interesting Indigenous Heritage Features in my perspective are the history sites and cultural sites, which are ‘new’ in a document like this in the sense that they are not part of the suite of ‘classical’ archaeological features that we as Northwest Coast archaeologists are trained to identify. However, their treatment in the handbook is relatively thin, and could be bolstered with more specific examples. As another example, culturally modified trees (CMTs) are one of the most ubiquitous heritage features on the coast, but since they are covered in a different handbook published by the BC Ministry of Forests, they are not included by Mackie et al. However, the inclusion of CMTs along with high quality illustrations would have made for a more robust ‘one-stop’ handbook. Similarly, the text refers to common archaeological materials and artifacts, especially in a brief section on “Isolated Finds” at the end of the handbook, but it could be strengthened through more detailed descriptions and examples of these materials and how to identify them. Examples of the most common lithic tools and their defining characteristics, of bone tools, fire-cracked rock, etc., in an introductory section before describing the Indigenous Heritage Features would provide a lot of useful information for readers and for on-the-ground identification of the material clues that help us to determine the existence of the Feature. An interesting section of the text is the appendix on geoarchaeology, which makes the argument that we need to understand sediments, paleoenvironments, and landscape formation processes to effectively identify many Indigenous Heritage features. The section stops short of providing specific examples that could be useful for a field technician, and could be easily bolstered with images of the “diagnostic stratigraphy” of different site formation processes on the Northwest Coast.

Addressing these shortcomings would of course make for a much longer text that perhaps goes beyond the scope of what Mackie et al. set out to accomplish, and this should not detract from the fact that in most ways the Indigenous Cultural Features Handbook has accomplished its stated goals. The utility of the handbook as a reference to identifying the material (and immaterial) evidence for First Nations’ long and persistent impacts on the coasts of the continent should not be understated. The text will be a useful aid in many field-based courses, and, if I don’t have a hard copy on me at the pub next time someone asks me ‘but, what is there to find out there?’, then I will direct them to the freely available PDF online.

*

Bryn Letham is a professor of archaeology at Coast Mountain College in Prince Rupert and an adjunct professor at Simon Fraser University’s Department of Archaeology.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster