‘Spiritual meaning, form, and function’

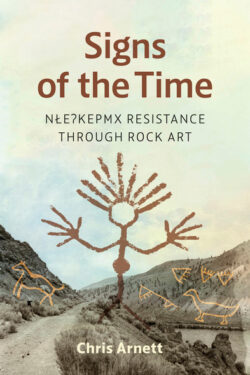

Signs of the Time: Nłeʔkepmx Resistance through Rock Art

by Chris Arnett

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2024

$39.95 / 9780774867962

Reviewed by Wendy Burton

*

Chris Arnett’s book is detailed examination of pictographs – rock art paintings in the central interior of British Columbia. Arnett’s purpose is to examine paintings in their contexts, because paintings have specialized spiritual meaning, form, and function. Arnett integrates cultural and technical aspects of rock art and rock art sites from start to finish. He insists the paintings in many settings are an interaction between the rock formation, the setting, the paint, and the artist, including the artist’s songs and stories about the site. Arnett weaves between ontologies and epistemologies, so that Indigenous and Westernized ways of knowing are juxtaposed and often in contradiction. Arnett’s intentions are many; he is especially determined that “Indigenous rock art” could play a significant role in protecting the ecosystem from the industrial exploitation of late-twentieth-century capitalism, the explicit intention of They Write Their Dreams on the Rock Forever. Indigenous rock art played a significant role in protecting the ecosystem of the Stein Valley from industrial exploitation.

Rock art was a form of perimeter defence used by Indigenous specialists until the mid-nineteenth century in an effort to keep European-introduced diseases at bay. Arnett examines Simon Fraser’s response to the rock art sites he encountered, including Fraser’s unfamiliarity with the Nlaka’pamux Tsaxali (Transformer) stories, stories that provided insight into the meaning of the paintings. “For those who know the story, these simple lines scored into the granite validate access to the most important ‘economic’ resource on the Fraser River – salmon.”

Pictographs represent dreams, visions, guardians, important events, prophesies and way markers. Pictographs have many interpreters, all of whom view the art from their own perspectives. Arnett is clear about this, separating the Eurocentric interpretations from the guarded explanations from Indigenous knowledge-keepers. Indigenous informants are careful to restrict their explanations, reminding the attentive researcher that the ‘absolute’ meaning remains unknown, because “he did not know the other person’s dreams, experiences, etc.” Arnett advises the reader that rock art “…could be understood only in terms of the beliefs, values, and metaphors in the mythologies and ceremonies of the people who produced it.”

This is not a book for the faint of heart. It is not intended as a popular guidebook to sites of rock art in British Columbia. It provides a thorough, well researched explanation of rock art, pictographs, and rock art sites of the Interior Salish peoples painted from the late eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. “Against the backdrop of colonization, pictographs are signs of strategic resistance and resilience when we consider what is known of rock art practices in the nineteenth century.” Hence the subtitle of this book.

Many of the sites can be understood more completely by understanding the relationship between the artist(s), the stories of prophesy, origin, and moral lessons, and the site – the rock itself. The historical context is important and often ignored or unknown: “[the pictograph] is always made under circumstances specific and historically contingent.” The search for ‘what does it mean’ is set aside in favour of an ongoing open investigation based on local knowledge, historiography, analysis of colonization and its varied impacts on Indigenous practices, and the ongoing decolonizing of Indigenous ways of knowing. Because much of what is known about sites that are no longer legible – if that is the correct term – Arnett is careful to give the reader the transcript of the interview or journal entry and then provide an interpretation by situation the informant in the context of the rock art.

The illustrations in this book are in black and white, and although Arnett provides detailed explanations of the photographs, they remain difficult to discern. This book is not a field guide to rock art sites, although Arnett provides pages of diagrams and comparisons to aid the reader. Those with familiarity of the travel corridors and the more than 50 locations could find the sites that are still discernable, but that is not Arnett’s intention. Far from it.

This book is a love song to those who painted on and with rocks in the Stein Valley and surrounding areas. It is a love song to those who have investigated such sites and their artists in search of meaning. Arnett invokes James Teit, Annie York, Ruby Dunstan, and somewhat less kindly Franz Boas, and amateur anthropologists with their Eurocentric interpretations of the paintings and their artists and their meanings. Signs of the Time can be read as a companion to the co-authored book They Write Their Dreams on the Rock Forever (York, Daly, and Arnett, 1993).

While this previous book was intended to be part of the defence of the Stein Valley against logging roads intrusion, Signs of the Time reads like a culmination of Arnett’s many years of research. It is not unusual to read a paragraph that has two sentences and eight lines of citations. This book has black and white photographs, diagrams, chapter notes, glossary, a formidable twenty pages of references, and an index. This book is not a quick read if one intends to try to sound out the words, read the relevant chapter notes, and check the references every page of so. It’s worth the effort, though.

Arnett uses the current orthography for the Nlaka’pamux language, which I cannot reproduce because I don’t have that font on my word processing program. One of Arnett’s explicit intentions is to bring the more accurate and authentic spelling (and therefore sounds) of the language to the reader and encourages us to try to sound the language and read it as part of the effort to understand the meanings of the art and to honour men or women who knew how to use the tәmt (TU-mlth), the red ochre paint, and more importantly, who knew the words or the song that gave the paint its agency.”

Who is this book for? This book is for scholars of many disciplines: epistemology, archeology, art history, Indigenous studies, and history. This book is for those who want to develop their understanding of the land they occupy, the interactions between place and people, and the intricate artistic expressions that allow the attentive to “negotiate the physical and spiritual worlds via the agency of the paint.” This book is for those who enjoy an ontological mystery. This book is for those who live their lives through story.

Chris Arnett is a writer and carver, a fourth-generation settler on his mother’s side and a member of the Ngai Tahu, a Maori tribe on his father’s side. He was born and raised in British Columbia, teaches in the Department of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, and has a life-long interest in rock art and rock art sites, especially in the Stein Valley.

May this book send you looking for Arnett’s The Terror of the Coast (1999); At the Bridge by Wendy Wickwire (2019); and They Write Their Dreams on the Rock Forever (York, Daly, and Arnett, 1993), and that’s just for starters.

*

Wendy Burton is Professor Emerita at University of the Fraser Valley, where she taught academic and work place writing, story-telling, diversity education, and educating for social justice. Throughout her work life, she wrote creative non-fiction, long and short form fiction, and poetry. Her debut novel Ivy’s Tree was published by Thistledown Press in September 2020. The first two chapters of her current project, Millicent, are published in Embark (October 2020). “Swimming in the Dark,” the creative nonfiction account of her effort to qualify to swim the English Channel was published in FolkLife in October 2020. This essay was awarded Gold, BC Story of the year by Alberta Magazine Publishers Association in 2021. “Meditations on The Headstand: Life in a (fat) body” is in FolkLife Winter 2023. The first draft of Millicent, the fictionalised account of her great-great-grandmother’s life in London’s East End in the 1850s, earned her a Letter of Distinction from Humber College Graduate Certificate in Creative Writing in 2020. Millicent is currently being considered for publication by a Canadian independent press. [Editor’s note: Wendy Burton recently reviewed books by Susan Blacklin and Tara Teng.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster