Terrifyingly-sequenced photographs / artifacts

Delirium

by John O’Brian

Vancouver: Delirium Editions, 2024

$25 / 9781738144808

Reviewed by Ryan Gauvin

*

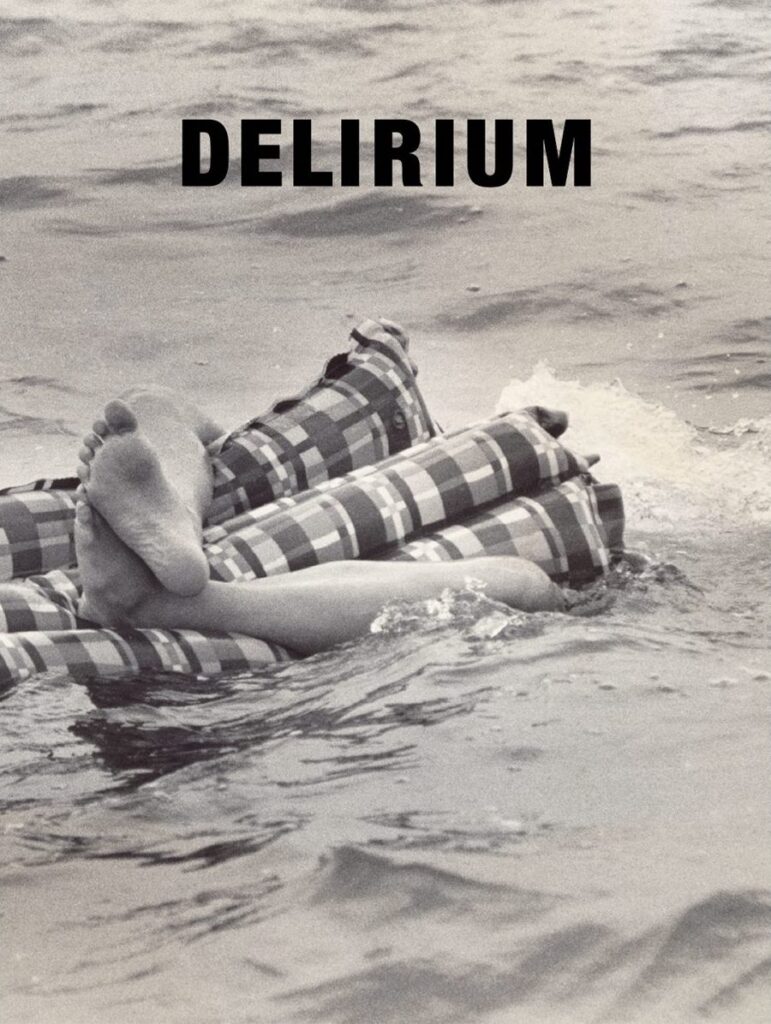

A natural response to first picking up Delirium by Vancouver-based art historian, artist, curator, and professor emeritus John O’Brian, is to flip the book over in the hopes that the rear cover might resolve the peculiar scene we are faced with on the front: a pair of legs wrapped tightly around an air mattress floating in open water. The upper body and head attached to those legs are fully submerged, and bubbles rise to the surface. The rear cover, showing the left portion of the same photograph bled across the spine, reveals a second pair of legs clinging to the mattress. The cover image situates the viewer in a state of uncertainty, nay anxiety, holding our breath and straining to right ourselves vis-à-vis the disorienting photograph. This sets the tone for this aptly named book of photographs.

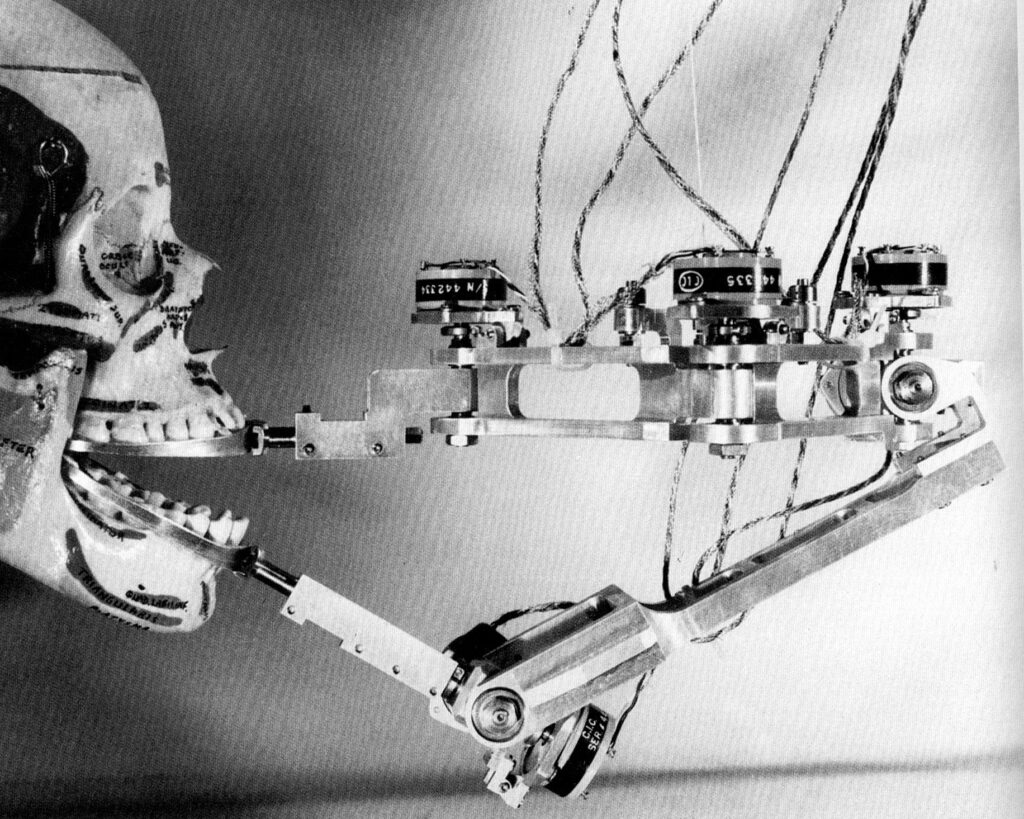

The word delirium, coming from the Latin ‘de lira,’ has agricultural origins: ‘to deviate from the furrow.’ These photographs, appropriately, are outcasts themselves, prints made by newspapers and press agencies over the past century, only to be discarded in the frenzy of digitization and sold for a song on e-commerce sites. Wherein other press photographs have found their way into university libraries and archives, these unwanted prints, divorced from the context of their creation and purpose, have been scattered outside the furrow. It is fortunate for us then that John O’Brian has rescued these homeless photographs and, on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, has curated this dizzying survey of seemingly disparate photographs. Through their careful arrangement these images find new meaning, drawing our attention to the “Faustian bargain struck by modernity in the name of scientific advancement and consumerism” as noted in O’Brian’s brief afterword, Delirium‘s only hint of a textual guide.

John O’Brian was born in Bath, England on April 2nd, 1944. As the story goes, he was born on April 1st, but a sleight of hand at signing the birth certificate prevented him from being labeled an ‘April Fool.’ O’Brian, who has been based in Vancouver for the past 37 years, has enjoyed a long and productive career as art historian and occasional artist since completing his PhD at Harvard University, where he established himself as a proponent of social art history and a sharp critic of the production of art under the social arrangements of capitalism. He began his tenure as a professor in the department of Art History at the University of British Columbia in 1987, where he has taught and written on such diverse material as the Group of Seven painters, the art criticism of Clement Greenberg, and the intersection of photography and the atomic bomb. He has mentored countless graduate students and has served the artistic community as a curator, exhibitor, researcher, advisor, and board member of various galleries and museums, including the Vancouver Art Gallery, The National Gallery of Canada, and the Polygon Gallery. O’Brian officially retired from his university duties in 2017, but this was a retirement in name alone, and he continues his tireless work researching, writing, and advising students and institutions.

Delirium is one such project undertaken in his retirement, though it is the result of decades of collecting, researching, and viewing photographs.

Delirium, almost entirely absent of text save for O’Brian’s brief afterword, sits is a departure from his catalogue of written works. Devoid of captions aside from dates under each image, the seemingly disparate selection of photographs, individually, offer little in the way of meaning or information as discrete documents. The brilliance of the book rather, is in the careful sequencing, with each photograph connected to the one before and after either through the photograph’s content or through its aesthetic similarities or contrasts. The result is a viewing experience that, starting with a moment of calm, revealed in a 1972 photograph depicting a data collector observing his instruments while standing waist deep in water, quickly becomes frantic, scattered, and deranged, as the sequence of photographs unravels. Moments of rest are scarce. To view the book from cover to cover is akin to a feverish dream.

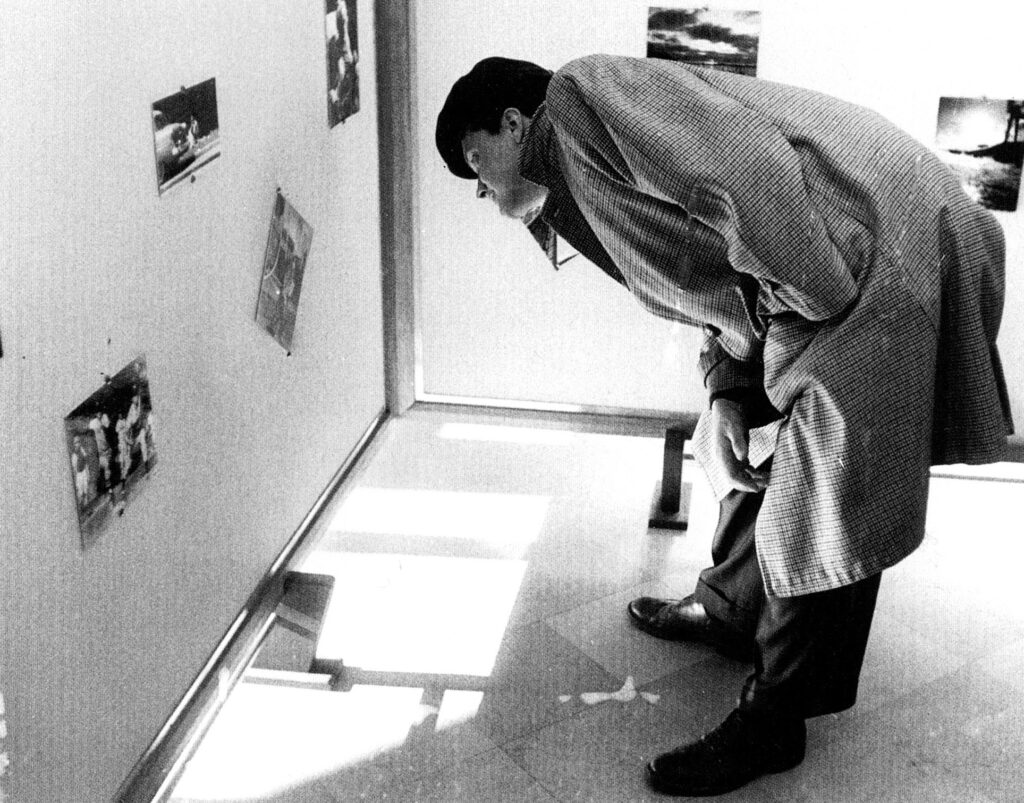

There are similarities between Delirium, and Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s 1977 book, Evidence, for both draw upon found images in the public domain and both defy meaning upon first survey. But rather than taking defiance of logic and coherence as its end, Delirium demands closer consideration that situates the dizzying sequence of photographs in the capitalist illogic of the 20th century. Images of technological advancement, war, consumerism, and ruin weave in and out of one another fluidly, while maintaining a tension that suggests that their balance, on the page and in reality, sits precariously on the verge of self-destruction. This only lends to the anxiety of the viewing experience. Interspersed throughout Delirium are photographs of people – groups or individuals – looking. This look is sometimes casual, and sometimes it is close-focused, but these calm faces are mismatched with the tumult on the surrounding pages that swirl around them. Rather, these onlookers, with whom the viewer may or may not choose to identify, sit eyes-wide-shut to the destructive illogic of unfettered capitalist growth. If these are what one versed in photographic layout might call the ‘rest pages,’ the rest is intensely uncomfortable.

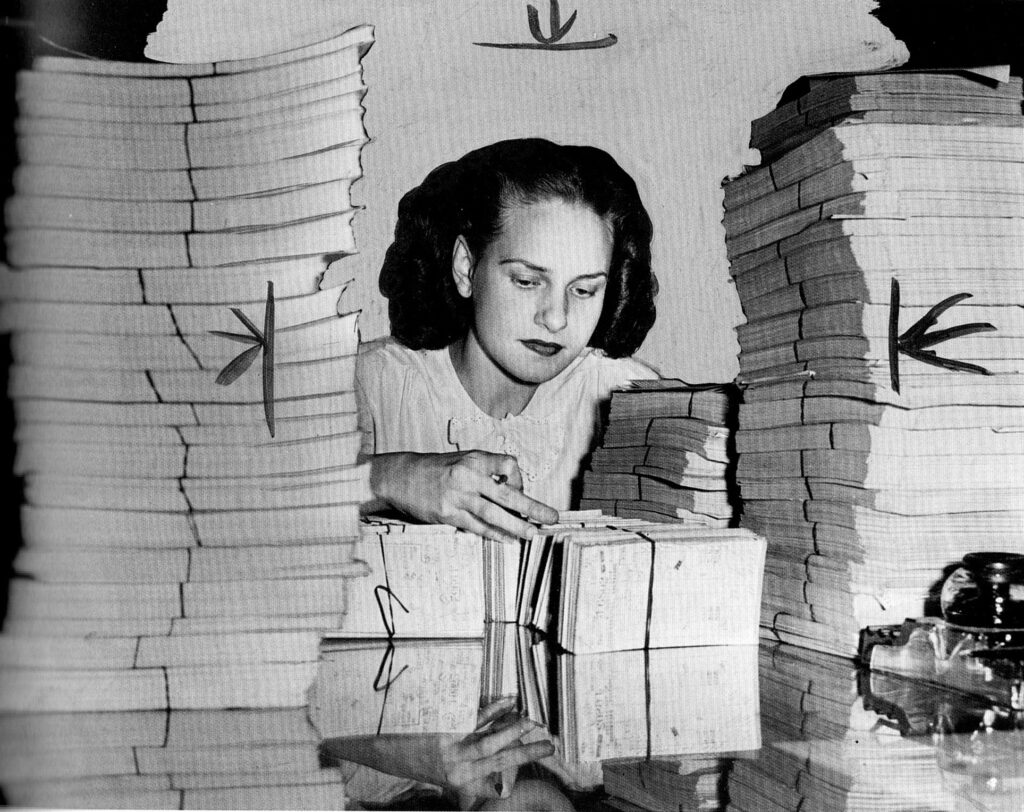

At one point in Delirium, we see a woman surrounded by large stacks of paperwork with arrows drawn in grease pencil on the print face, attempting to focus our attention on the woman and not the stacks, though they are oppressively present. The next photograph places a stack central, but here it is the exhaust stack from a nuclear power plant with its mass of steam, alluringly backlit in this night photograph, billowing in the wind. On the facing page we are presented with the carcass of a burning building, also photographed at night, with smoke and flame mirroring that depicted in the adjacent image. The two images together signal a transition from calm to chaos. This pairing is followed by an aerial photograph of a row of cookie-cutter suburban homes, inundated by flood water and detritus. The angle of the homes, cutting diagonally across the page is matched by the next scene, depicting a row of scattered cash registers, electric kettles, and other technological trash, sitting in a snowbank, awaiting garbage pick-up. And the sequence continues, unrelenting. The sly ‘stack’ pun, if noticed, provides the viewer with a sense of accomplishment, like finding a word to a crossword puzzle, at the very moment that they are faced with the masterfully shot image of the nuclear plant. O’Brian then takes that complacency, and quite literally destroys it in the following images. The smugness of that brief moment only accentuates the self-reflexive horror of the one that follows. The logic of the sequencing, acute as it is, is terrifying. The intersection of nuclear technology and photography is subject matter in which O’Brian is well-versed and has been a major focus of his research and writing, as well as the topic of his Camera Atomica exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario (2015). However, drawing the viewer into playing out this ambivalence-cum-self-awareness through unwritten wordplay and visual cues, gives an indication of just how deep his connection to the subject matter is. It is but one poignant moment in the frenetic, potent sequence of photographs.

As with many of the great photography books of the past century, such as Robert Frank’s The Americans, or Gilles Peress’s Telex Iran, a first viewing might stir emotion, sometimes quite strongly and with lasting effect, however it is an alert and careful viewing of these enigmatic works that is most rewarding. O’Brian, like Frank or Peress, has connected these photographs in ways that are likely imperceptible to the distracted or passive viewer. Which is perhaps the crux of the work, for unlike their filed, annotated, and infinitely reproduced counterparts, the photographs presented in Delirium are the discards of history, otherwise unviewable to the public. Seeing is the beginning of perceiving, and O’Brian has started the work for us by giving these photographs an afterlife. But O’Brian, rightly, leaves the task of deciphering the relationality of these discarded photographs, as well as our own complacencies and anxieties, to the viewer.

The final image of the book depicts a man, bent over, looking at photographs haphazardly pasted to a wall. He cocks his head awkwardly, orienting himself to the knee-level pictured scene. Upon first viewing I thought this photograph might be a sort of imagined self-portrait of O’Brian in the throes of sequencing the book. It may well be. And yet upon repeated viewings, my opinion of that final image has changed. I now see it as my own self-portrait, straining, and often failing to find order in the surface of the images that preceded it. As in a state of delirium, meaning evades our grasp, but the last image sends the viewer spiraling back to the first, where meaning is promised just below the surface.

*

Ryan Gauvin is an art historian, seed grower and sometimes-photographer residing in Lorette, Manitoba, where he spends his summers undermining the hybrid seed industry through his open-source plant breeding efforts, while reserving the long Manitoba winters for research and writing on the intersection of documentary photography, politics, and ideology. Originally from Vancouver, British Columbia, Gauvin holds a BA in Geography from Simon Fraser University, an MFA in Documentary Media from Toronto Metropolitan University, and a PhD in Art History from the University of British Columbia.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster