‘A dialogue respecting traditional objects’

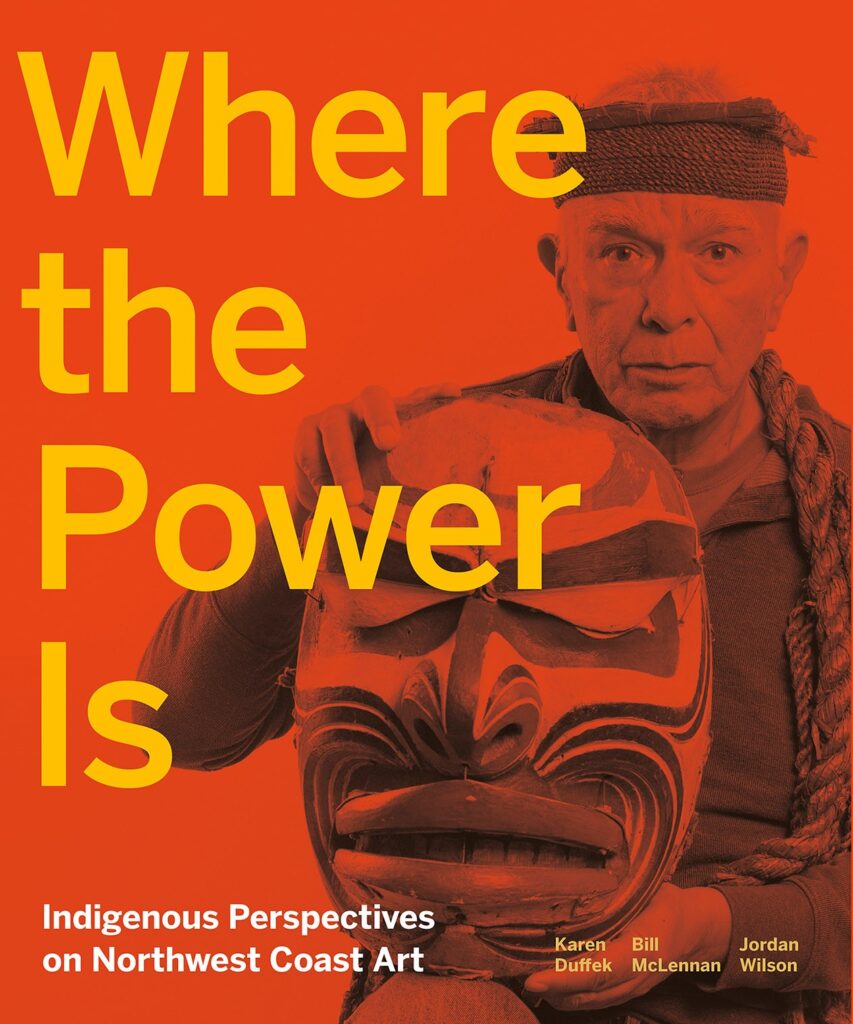

Where the Power Is: Indigenous Perspectives on Northwest Coast Art

by Karen Duffek, Bill McLennan, Jordan Wilson (eds.)

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, in collaboration with the Museum of Anthropology, UBC, 2021

$65 / 9781773270517

Reviewed by Richard Butler

*

Published in 2021, Where the Power Is contains a series of reactions and reflections by members of the Coastal Peoples in response to objects from the collection of the UBC Museum of Anthropology. The book was much-heralded, a finalist for the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize, at the BC & Yukon Book Prizes, and won the City of Vancouver Book Award and yet has somehow not previously been reviewed here.

It is a remarkable book—in effect, an interactive version of the Museum of Anthropology itself. It features diverse voices engaging in a dialogue respecting traditional objects and their power.

Sumptuous plates of the artworks appear alongside photographs of the individuals to whom they are most closely connected, and with whom they are in dialogue. Interspersed are scholarly background descriptions.

The book opens with an essay from two of its “curators,” Jordan Wilson and Karen Duffek, entitled “Into the Present,” which provides a thoughtful and forward-looking overview of art historical and aesthetic approaches to Coastal Peoples’ artworks.

*

The purpose of the present review, so long after publication, is to reflect on developments over the past five decades since a similar dialogue took place in that same venue with respect to many of the same pieces.

That prior dialogue took place between two of the most prominent voices of their day, Bill Holm and Bill Reid. It also was turned into a book. 1

Comparing the two books points up how far Coastal Peoples’ own conceptions of the appropriate uses of their artworks have come in the intervening years, and provides guidance to the rest of us on what appreciating Coastal Peoples’ artworks really involves.

A number of the same pieces appear in both books. One such item is the ivory or sperm whale Tlingit dagger head, discussed as Item 7 in the Holm-Reid dialogue and on pages 312 and following in Where the Power Is.

Here is part of what Bill Reid had to say about this piece:

These people looked at the world in a very different way than we do. They weren’t bound by the silly feeling that it’s impossible for two figures to occupy the same space at the same time …, coexisting in space and time. …. I like complexity. I like the whole way the artist just went crazy with imagination. In detail, it’s marvelous. A human face which is also a part of a bear’s head! Of all the pieces we’ve looked at so far, I’d like to own this one.

In Where the Power Is, the comments from Nuu-chah-nulth ceremonialist Ki-ke-in Ron Hamilton about the dagger head help us take a step toward a more modern, culturally informed, response to Coastal Peoples’ artworks:

Somebody spent a lot of time thinking about this, and then realizing it. It’s so masterfully achieved. But do we stay there? Do we stay focused on that, and not get to the other things that are going on? There’s a whole lot more power, energy, and substance in this than just a conglomeration of figures. [Intelligence, metaphor and poetry] are inherent in our languages, ceremonies, rituals, songs, carvings and paintings. It makes sense to look at this piece in those ways, to raise questions, and to wonder. ….

[This piece] shows connectedness—you can’t say that the little bear is just perched on the bigger one. Then, the little man is absolutely integral to the bear and seems to be piercing him. …. If you believe that this can really happen—that things can occupy the same space at the same time—what does that do to your behavior? How does that cause you to behave? How do you function in the world believing that?

Reid recognized the same essence in the dagger head as Ki-ke-in did. Yet there was a notable difference between their respective personal responses to it.

Reid’s response evinces an evolution of traditional Indigenous aesthetics toward mainstream contemporary thinking, individualism as in Reid’s own artworks, and a measure of commodification.

Ki-ke-in’s response goes in a completely different direction. It reflects an activism in response to what I have elsewhere termed the artwork’s “whole substance.”2

*

Where the Power Is describes “whole substance” in terms of the evolution of meaning of Coastal Peoples’ artworks through time.

Since time immemorial, objects have moved up and down the coast in what some have called “ancient silent conversation.” They are said to have “accumulated meanings in their early journeys through Coastal Peoples communities, whether by gift, trade, or as the spoils of war. These things never lost the oral histories and clan relationships they represented from time to time.”

Again, according to the curators’ opening essay in Where the Power Is, Coastal Peoples do not view artworks as things owned by one person or another. From their perspectives, these things are better described as “belongings” in the broadest sense of the word. They are legal documents in that they endow and legitimize rights, privileges, and responsibilities, an ongoing connection to governance and stewardship.

Yet those meanings and that concept of belonging do not accompany the objects when they were eventually sold or traded outside Coastal Peoples communities. As a consequence, the objects came to be admired for their aesthetics and form, a “disembodied creation of a distant Other.”

Nevertheless, as the curators argue, and as the rest of the book’s contents vividly show, “[n]o matter how far the material objects have travelled, each piece anchors intangible knowledge to real places of origin, and to real people past and present. This knowledge persists in communities, despite the objects’ absence.”

The main point made by this book is that traditional objects as belongings were created and still exist as part of social networks beyond the museum’s walls.

As Marika Echachis Swan puts it, seeing them in the museum is like visiting relatives in hospital. “They’re so happy to see you: ‘Thank you for coming to see us here.’” Yet conversations with those objects and belongings are more difficult, she says, when community members visit museums: “Because the objects are behind glass or in storage, it doesn’t have the same intimacy.”

The artworks reassume their personal meaning and intimacy when they return home, as happened with the presentation of regalia by Kwakwaka’wakw Hilamas William Wasden Jr., reactivating at his first potlatch a ‘museum piece’ carved by Arthur Shaughnessy during the time of the potlatch ban.

Its’ futurity was guaranteed [on that occasion] when … Beau Dick carefully took his knife to the inside of the headdress to modify it to better fit the wearer. The fresh cuts are almost impossible to see when it sits on the museum shelf. But like the songs and dances that accompany its use, they represent adaptation to affirm the continuum, the kind that has always taken place in the Bighouse behind the ceremonial curtain.

Showing items through dance and ceremony keeps the history of belonging alive. To do so it is important that items such as headdresses are kept or repaired or otherwise made ready to be danced.

*

Modern Coastal Peoples’ artists use the word “aesthetics” in the Western, colloquial sense. But these cultural objects, as T’uu’tk Robin Gray tells us, are “not just aesthetic pieces, something to look at and admire. They represent the integrity of our ways of knowing, being, and doing. They’re teaching aids. They’re pedagogical tools, in the Ts’msyen worldview. We learn from them: from the stories they tell, from the construction of something that makes us who we are as Ts’msyen people.”

Tayagilaogwa Marianne Nicolson likewise takes what might be termed Coastal Peoples’ aesthetics a further step beyond simple enjoyment of beauty. She says artworks are not romantic objects from the past, but “land title pieces” that speak to ceremony, place and connections with land. Without those connections, she says, “[it’s] a loss—not just for us, but also for the public, in terms of their understanding of these things and their relationship with Indigenous peoples. Rather than getting stuck on aesthetic beauty (i.e. in the Western sense), “we need to reconstitute these objects and their meanings back into our political actions. To me, that’s far more interesting than looking at them for their formal qualities—even though it’s hard not to, because they’re so beautiful.”

She continues:

Because each of these objects ascribes certain rights, if they are simply reduced to their formal qualities or their entertainment value, we are really missing the point in them. I think a lot of the value for us of the engagement in, and looking at, these pieces ties back into this politicization. It does continue to go back to the land. [I]f these objects are [viewed in terms of conventional] aesthetic[s], then their meaning changes—and they are no longer speaking for us. We are fighting not to be absorbed politically, and we’re also fighting for our culture and our art not to be absorbed as colonial, institutional objects. Our spiritual responsibility is to that place in which we had an ancient, ancient relationship. ….[Elders’] teachings are embodied is these objects. … We want a real relationship … where all of these things that we’re talking about can be recognized within the work—not just the formal qualities.…. What we’re asking for … is to meet us further in. Because if you meet us further in, there are amazing things that could be known, and we could transform our society.

And so, when T’uu’tk Robin Gray looks at the traditional art forms, she sees

the integrity of who we are as a people that relates directly back to our homelands, our language, our expression of humanity, our responsibilities to places, to processes, to people, to human and supernatural worlds. …. You might not be able to interpret it automatically the way we do. But know there’s an interpretation that exists and is still enacted through community, through ceremony, through reclamation, through embodiment.

They seem to be talking about a kind of respectful and meaningful community belonging. That is really where the power lies. From time to time, these artworks may have belonged to one person or another, in one community or another, changing their identities as they went; but as time has passed, and the objects have passed through many hands, taking on additional meanings in the process, eventually they can come, in a culturally informed way, to belong to all of those communities and the communities can come to belong to all of them.

Reciprocal belonging. Or, in other words, reconciliation.

*

Richard Butler is a latter-day settler living on the traditional territory of the lekwungen-speaking Peoples, a retired lawyer and sometime law professor, and more recently a writer on various Indigenous subjects. He is the author of Taking Reconciliation Personally & I Dare Say… Conversations with Indigeneity, published through A & R Publishing, and recently reviewed the published work of C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan (eds.) and Aaron A.M. Ross for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “‘A dialogue respecting traditional objects’”