Disorientation, reorientation

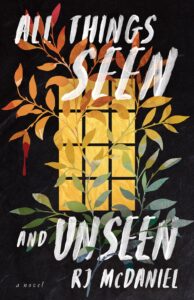

All Things Seen and Unseen

by RJ McDaniel

Toronto: ECW Press, 2024

$24.95 / 9781770417090

Reviewed by Petra Chambers

*

Beginnings are tricky. All Things Seen and Unseen, by Vancouver resident RJ McDaniel begins brilliantly with a short, dynamic sentence that introduces unease and relational tension, two major themes of McDaniel’s debut novel: “Alex watches as the nurse’s eyes follow her.”

All Things Seen and Unseen is both quick paced and patiently narrated, conscientiously tracking the perceptions of the protagonist, Alex Nguyen. From the first paragraphs, McDaniel immerses readers in the subjectivity of Alex’s experience; and while they fall for Alex, mysteries keep popping up on almost every page.

This story is about reclaiming self, memory, and sovereignty, and it does not treat these subjects superficially. The portrayal of a protagonist with a traumatic history is rendered with sensitivity and nuance.

McDaniel introduces Alex through a series of crucibles: constraining circumstances that force transformation. (I recently took a writing workshop about crucibles with ’Pemi Aguda and I was thrilled to find them used so effectively by McDaniel). There are physical crucibles that Alex can’t escape from and others she/they tries unsuccessfully to hide in. A past relationship is an emotional crucible. Transphobic violence is a terrifying social crucible. Alex is unsafe, exposed, and ensnared, over and over again. Yet McDaniel also uses peripeteia (reversal of fortune) effectively, swinging between moments of hope and scenes that shimmer with sketchiness and feel like doom. For example, Alex idealizes an opportunity to housesit for a friend’s parents on a Gulf Island, but this fantasy is undermined by a series of disturbing and uncanny events that occur as Alex travels to a new home.

Is Alex hallucinating? I wondered. Can her/their perceptions be trusted?

These are salient questions, for both Alex and the reader.

Alex keeps checking her/their perceptions of threat, explaining them away as paranoia (“…no one is watching…there is no ominous sub-plot…”), but as All Things Seen and Unseen unfolded, I increasingly questioned whether Alex’s fears were warranted:

After all the time they spent doubting everything they saw, everything they felt, repeating over and over that they weren’t in danger, they were never in danger, there was no one watching, nothing bad had happened—after all that time feeling the truth, knowing the truth, and trying to make themselves forget. No wonder they never seem to be standing on solid ground, but their perceptions distort and fade like shadows: how long have they been denied their own narrative?

Alex encounters homophobia, racism, and transphobia. Acts of violence. In addition, there’s something sinister and unexplained lurking in the periphery of almost every scene. Early in the novel, Alex mentions that her/their mother believed in ghosts. This information lends credence to the possibility that otherworldly forces may be at work.

But why is Alex in so much pain? Was she/they assaulted? Does she/they have chronic pain? Is she/they imagining it? People with chronic illness frequently have their symptoms dismissed. As a reader I didn’t know what was real. Once again, I asked: Is Alex hallucinating? Can her/their perceptions be trusted?

McDaniel drops hints but leaves lots of space for ambiguity. This is a story about disrupted memory—the perfect context for a mystery: a protagonist with a history of trauma, trying to find stable footing in an unsteady world, while experiencing disruptive flashbacks:

She has the feeling, as she does often, that she used to remember more. The memories come to her in flickers, like small flames, and to move too quickly toward them snuffs them out before she has a chance to feel their quiet heat.

Through dysphoric shifts of pronouns, McDaniel amplifies the uneasy feeling of unreality that weaves through the narrative (the seen and the unseen: the remembered, the disremembered). The dissonance falls away when Alex is in the ocean and the lake. While swimming, Alex’s pronouns are restored:

There it is again. Their body. It is theirs, not hers, theirs, their world, their little pile of clothes and glasses barely visible on the now surprisingly distant shore. It keeps happening lately, this slipping back into the old pronouns, the ones they used back when they envisioned a life extending into the future.

Sometimes when I read fiction, I fall into a fugue state—the story infuses my life and I become a strange hybrid conglomeration of merged reference points. I’m no longer sure what is and what is the story living through me. That occurred while reading All Things Seen and Unseen voraciously over two days. Being consumed by a story is always a bit destabilizing, but in this case the experience was extra, compounded by McDaniel’s (exceptional) treatment of the protagonist’s disorientation. My disorientation melded with Alex’s, and the combination almost made me dizzy.

I’m a more compassionate person after reading this book. I feel less alienated from the humans, who—I admit—sometimes scare me. So, my verdict: this is good art. It provoked me and changed me, in big and small ways.

Here’s a small way: I’m a person who lives on one of the Gulf Islands and who feels a certain way about tourists. I tend to categorize people as either ‘from here’ or not. I enjoy how McDaniel uses this common attitude among islanders as a menacing feature for one of the antagonists. Because it is kind of creepy.

Any kind of ‘us and them’ is creepy.

Finally, we don’t love novels for their spines, but when a book ends up on the shelf, that’s what we see. All Things Seen and Unseen has one of the most attractive, colourful spines I’ve seen in a long time. It looks good on my bookshelf, and I think it will on yours too.

*

Petra Chambers (she/her) lives in the traditional territory of the Pentlatch people. She writes creative nonfiction, poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms. Her work has been published by PRISM International, Queens Quarterly, The Fiddlehead, CV2, and Prairie Fire. She is the 2024 Yosef Wosk Fellow for the Vancouver Manuscript Intensive. Her first poem was nominated for a 2025 Pushcart Prize. [Editor’s note: This is Petra’s first book review for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Disorientation, reorientation”