Colonial diary for historical context

Reading the Diaries of Henry Trent: The Everyday Life of a Canadian Englishman, 1842-1898

by J. I. Little

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021

$37.95 / 9780228006619

Reviewed by Jeff Oliver

*

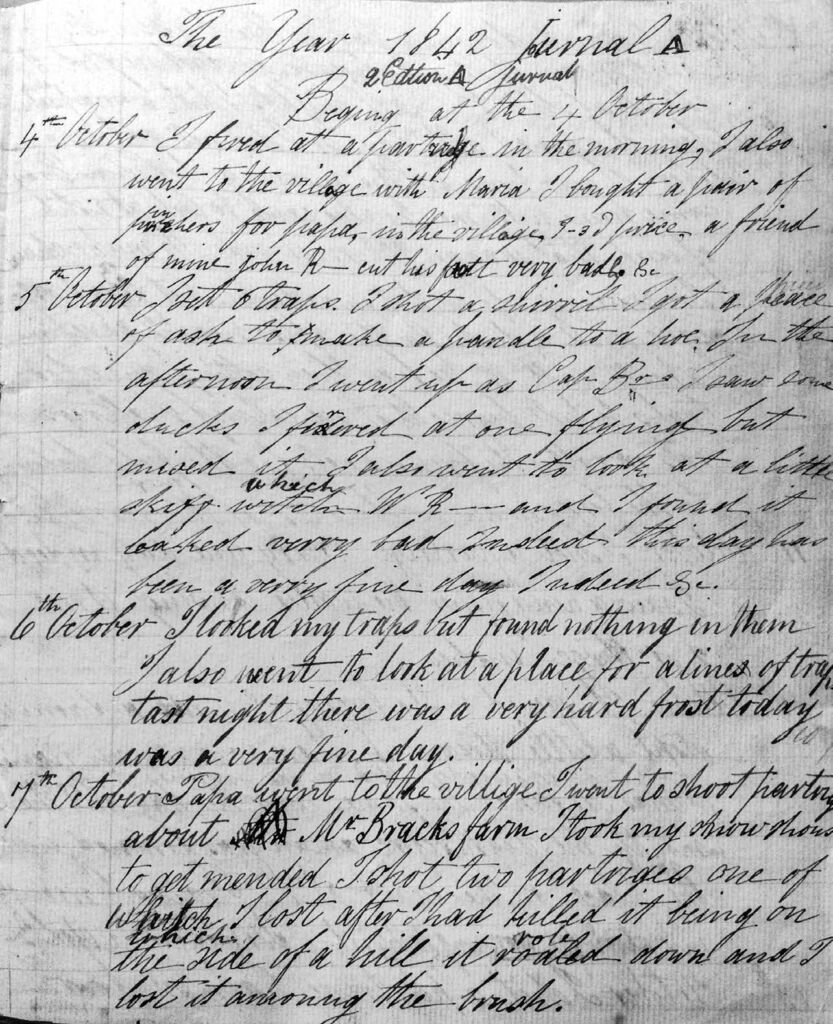

Diaries are crucial source for biographers and social historians of all stripes. But how to characterise a life in its historical context when many diarists focus on a much shorter ‘literary’ period? The diaries of Henry Trent – colonist, would-be prospector, jack-of-all-trades, woodsman, but mostly aspiring gentleman farmer and family man – were written, intermittently, over eighteen years of Trent’s eighty-year life, from 1842 – 1898. Ten volumes of neat (but poorly spelled) penmanship coving the second half of the 19th century, his adult life, provides historian J. I. Little an unrivalled qualitative vista into a rural history that intersected with a host of issues characteristic of the Victorian settler experience, from migration and colonialism to the farming economy and from environmental history to more introspective ideas about family life.

***

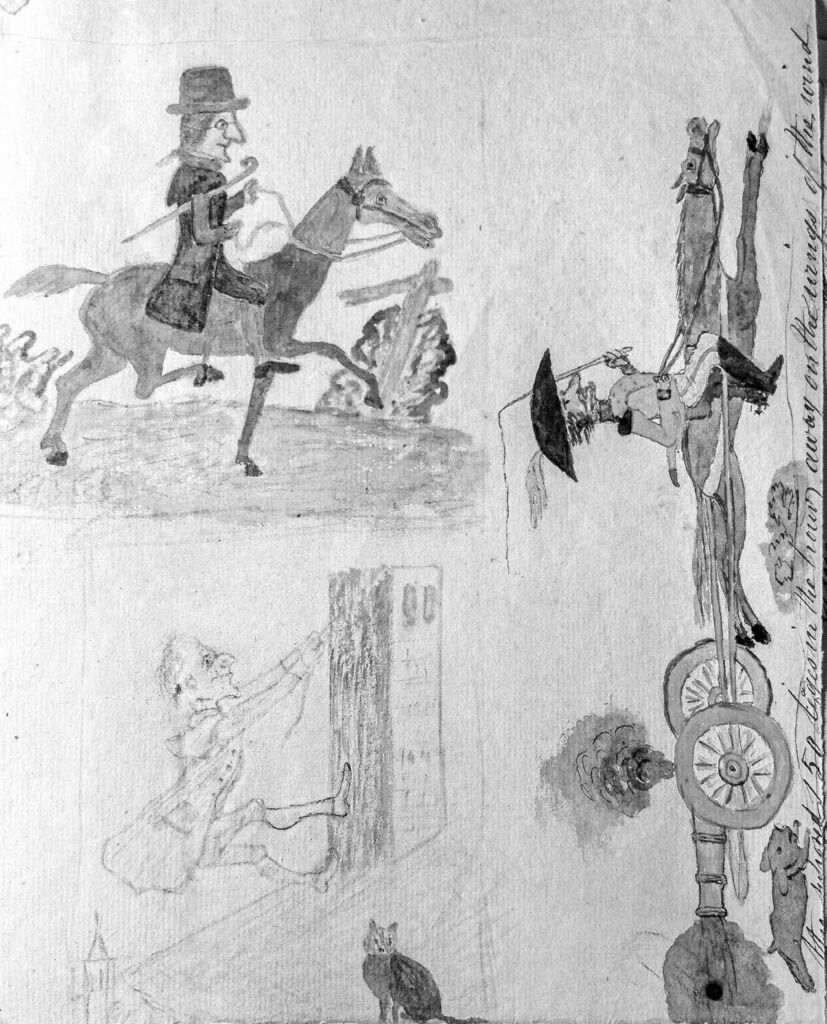

Henry Trent was born in Ely at the head of England’s fenlands to minor gentry in 1826. His father, a naval officer, moved the family to Lower Canada, eventually purchasing land on the St Francis River across from the village of Drummondville in the Eastern Townships. Early adulthood was spent on his family farm. As a mark of his family’s elevated status, he avoided farm labour, which was mostly done by servants, and spent much of his time hunting in the woods. Dissatisfied with the restricted world view from ‘Le Manoir Trent,’ his family’s large stone-built house, Henry fantasized about a more exciting life in the wilderness adventuring alongside the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The death of his overbearing father during a brief return to England presented him with the opportunity he was waiting for. Spending time in London, Trent learned of the ‘gold diggins [Sic] in…Frazers River in [British] Columbia’. He befriended a group of other young upper middle-class men champing at the bit for adventure (including the young Frederick Whymper, who took part in the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition and would later establish his reputation as an artist and author of the Northwest). Infected by the lure of riches, maps and guidebooks were purchased, and they booked passage on a steamship to Vancouver Island.

Over a year in Britain’s far-flung colony and not once did Trent make it to the gold fields. Convinced by stories the pay dirt was ‘played out’, he travelled north into the Comox Valley, built a log cabin twelve-foot square, apparently acting out his boyhood fantasies. He quickly learned his hunting skills were insufficient to keep food on the table. He learned the Chinook jargon and survived by purchasing deer meat from local indigenous people. As a colonizer, Trent represents something of an ambivalent character. That he took for granted that he could settle indigenous lands places puts him in good company with prevailing colonial opinion. But at the same time, his ‘openness’ to indigenous peoples, his assessment of their ‘honest’ character (possibly influenced by befriending an Abenaki boy in his youth), in contrast to more typical settler views, also suggests a more ‘enlightened attitude.’

Failure to establish a sustainable toehold up island saw him drift south to the port of Victoria. Despite his privileged upbringing, lack of funds required him to look beneath his station. To get by, Trent reinvented himself as a ferryman: he acquired an old boat and earned his keep by rowing sailors to and from ships in the busy harbour. Here we see glimpses of the sort of pragmatism and social boundary blurring that characterised much of his middle age and later life.

Sixteen months in British Columbia sated Trent’s desire for adventure. In 1864 we see him pitch up at his family farm on the St Francis River with twin aims: to establish a family and to bolster his social position within the farming gentry. He would achieve his first goal, but at the cost of the second. Living in a French and Catholic majority area, Trent swam in a world dominated by linguistic and cultural institutions that could be at odds with British upper-middle class values. But having spent his formative years in the region, knowledge of French combined with the necessity to work across lines of custom and class, provided him with a degree of respect among the community, if not unreserved approval. A Catholic wedding, requiring permission by the bishop, saw Trent take the hand of the much younger Eliza Caya, daughter of French Canadian bourgeoisie. The marriage would ensure stronger local business connections but would also serve as a mark of marrying down, ultimately frustrating his aspirations of membership within the colonial gentry. The life they made together resulted a large brood (in 1882 there were seven girls plus an infant son, with more on the way). Nearly all the Trent offspring were baptised with a combination of French and English names, suggesting the household was probably bilingual. The increasing significance of French within the household is reflected at a family picnic held in the ‘Bois de Boulogne,’ a pine grove near the house, a stark contrast from the British imperial place names applied by Trent’s long dead father.

What stands our most about Trent’s later life is his unescapable descent into the middle rungs of farming society as seen through the lens of life on the farm. Unlike his father who relied on farm servants, we see the Trent family having much more in common with their neighbours. Although they continued to live in the stone house and for a while had a small income from his father’s estate, day-to-day life was in synchronicity with his struggling neighbours shaped by the rhythms of the seasons. Much of Henry’s time was spent on the edge of a subsistence lifestyle, worry about their harvest of oats, potatoes and hay. Self-sufficiency was a high priority. They grew flax for the home production of linen and sold produce to neighbours ‘in kind’ for helping on their land. Eliza made soap and candles, and when the children were old enough, she threw her labour into farming. Some of the most frequent entries have Henry out in the woods cutting firewood or rails and pickets for fence lines. In this regard his life fell into place with the trope of the axe-toting settler from more popular narratives of pioneering. In his final diary entries in 1894 we read about Henry worrying about having enough wood to keep their large house warm over the winter. Somehow, they managed. He would live eight more years: his last breath was in 1906.

***

Histories of settler experience, all too often, draw tight lines between different categories of people. Identities of culture, class, and nation are often worn on the sleeve. Reading the Diaries of Henry Trent is valuable in showing contemporary readers that life’s choices have ways of kicking back against more expected plotlines. Trent’s life was full of boundary crossings, partly born from pragmatism, but also the fact that his life played out on the edges of institutional conformity (whether cultural, religious, or linguistic) where structural power was less suffocating, where rubbing up against other norms opened up possibilities. In this regard, Trent’s life was exceptional in negotiating the sets of relationships that served to create dividing lines between Englishness and French, Anglican and Catholic, or middle- and upper-class values. Aided by Little’s unfussy prose and capacity to put Trent’s life into the bigger picture, this book helps us to see, and to understand, how life histories are enmeshed within complex social and material worlds that condition and enable us to become different things.

*

Jeff Oliver is a landscape archaeologist with an interest in the recent past. He writes on material histories of colonization and the cultural and environmental strategies of settlers in both Western Canada and Scotland. He is the author of Landscapes and Social Transformations on the Northwest Coast: Colonial Encounters in the Fraser Valley (University of Arizona Press, 2010, paperback 2022 and e-book 2023). Originally from the Lower Mainland, he once took J. I. Little’s 4th year history course on New France up at SFU in the late ’90s. He is currently Head of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. [Editor’s Note: Jeff Oliver has previously reviewed books by Lauren Beck and Chad Reimer for The British Columbia Review]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Colonial diary for historical context”