This is a worrying book

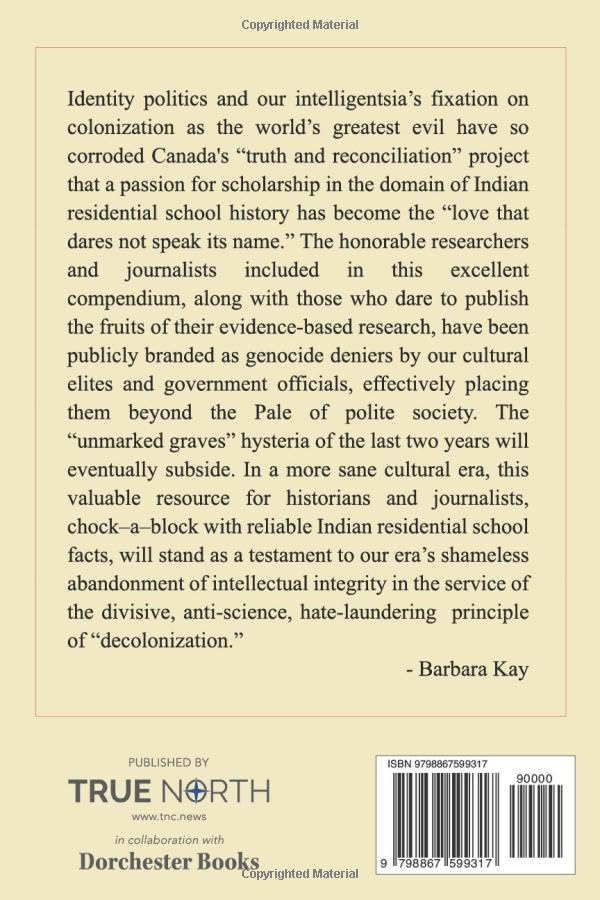

Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us (and the Truth about Residential Schools)

by C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan (eds.)

Ottawa: True North/Dorchester Books, 2023

$21.00 / 9798867599317

Reviewed by Richard Butler

[Editor’s Note: Recently, a controversy has emerged in the City of Quesnel, with a book at the centre of it. The British Columbia Review decided to look at the title which has caused so much debate and dissent within the community’s city council. Author and retired government lawyer Richard Butler reviews Grave Error.]

*

We live in an age of competing truths, of narratives, and counter narratives.

Grave Error sets out to counter the narrative that the historical and ongoing treatment of Indigenous people in Canada constitutes genocide; and that the residential school system was at the heart of it. There are points made which I agree with, but it is not for a reviewer to take sides.

In this book’s Introduction, the editors say the following:

Canada … is already very far down the path not just of accepting, but of legally entrenching, a narrative for which no serious evidence has been proffered. [It is a narrative of tortures and murders, secret burials, coverups and politicians blocking the truth from coming out.] This book is an attempt to appeal for rationality and truth amid a moral panic of stories about Canada that are so implausible that they should not be believed without convincing evidence.

Publication in book format [of the various contributors’ articles and podcasts] will make it easier for readers to appreciate that these questions are not just isolated queries or knee-jerk dismissals—but constitute a powerful, research- and facts-based indictment of the moral panic over residential schools … [an indictment which deserves] a degree of permanence [and availability] for future readers.

The editors admit that there is a certain amount of repetition from chapter to chapter, as might be expected in such a collection. Repetition is indeed a constant feature. It makes the book increasingly tedious to read. The book would have worked much better had the articles been edited with reference to one another, removing the repetition and emphasizing the various unique points.

The myriad of repetitions also presents a challenge for any reviewer. It is simply not possible to treat the chapters one by one or include all the issues raised. The best I can do in the space available here is provide a guide to general themes, focusing on points in select chapters of greatest potential controversy or interest.1

One final note by way of introduction. Unfortunately, this book is riddled with innuendo. The general thrust is that unmarked graves are a knowing falsehood and a money grab by Indigenous people. At law, such innuendo would be presumed false and malicious. As an authorial strategy, such innuendo is pernicious. It does not advance a reader’s knowledge of the truth of the matter, but rather builds on what he or she is thought to be capable of believing. In a book like this, on such an important subject, that is particularly unhelpful.

Jacques Rouillard, “In Kamloops, Not One Body has been Found”

Chapter 1 is a compendious version of our other authors’ telling of the counter narrative. A point-form review will illustrate what readers can expect to be repeated in other chapters.

In Chapter 1, Professor Rouillard describes:

- the announcement of the discovery of supposed graves of missing children at the former Kamloops Residential School;

- the panicked reaction by politicians and protestors without any actual evidence sufficient to prompt official investigations;

- the response of the RCMP, who are damned for intruding in the Tk’emlups matter and then damned for later backing off;

- the spate of official apologies and the international reactions to Canada’s having made them;

- the limits of ground penetrating radar and alternative explanations for the findings in the Kamloops orchard and elsewhere;

- the truth about the residential schools experience.

Rouillard continues by suggesting that the stories of missing and murdered children were simply made up:

Chief Casimir asserts that a certain gnostic ‘knowledge” of the alleged presence of children’s remains has been present within the community for an extended period—in spite of the fact that such “knowing” has nowhere been mentioned until the past couple of years.

He suggests, based on Frances Widdowson’s article (now Chapter 5 in this book), that the ultimate source of those stories was defrocked clergyman Kevin Annett2, saying:

[w]hether or not he was the first to invent the story … Annett either planted or reinforced in the “memory” of Indigenous people around Kamloops the belief that numerous childrens’ bodies were clandestinely buried in an orchard.

Rouillard thus joins with Widdowson, albeit by innuendo, in suggesting that the Tk’emlups graves announcement was and remains a cynical money grab. That same baseless innuendo is made repeatedly throughout this book.

The History of the Kamloops Apple Orchard

Chapter 2 provides a refreshing contrast. It sets out the several phases of the Kamloops orchard’s historical past, to contextualize and provide a reasoned basis for questioning the findings of anthropologist Dr. Sarah Beaulieu of possible children’s graves.

It is a detailed, fascinating, and balanced account of the history of use and excavations in the orchard.

One cannot help but wish that the Tk’emlups leadership had had access to this history when they engaged Dr. Beaulieu; because once they had done so, received her preliminary report and made their initial announcement, events were set in motion which have become increasingly difficult to reverse.3

How Media Fomented Moral Panic and Then Failed to Correct the Record

As a further refreshing contrast to conclusions based on innuendo, Chapters 6 and 11, by journalist Jonathan Kay, are notable for their balanced telling of the so-called ‘legacy media’s’ role in generating and maintaining the moral panic arising from the Tk’emlups graves announcement.

In the media’s defence, Kay notes that they reasonably expected hard evidence would soon be to hand. But none was forthcoming.

He then describes the “perverse incentive structure … whereby no media outlet had any interest in walking back … misinformation … [and thereby taking a] gratuitous reputational hit … when all your competitors are staying mum.”

In Chapter 7, James Pew, an online journalist, adds the following apt conclusion to the media piece:

Even if every one of the thousands of graves they find turn out to be children from residential schools, the fact will remain that the legacy media rushed to condemn the Canadian government and the Catholic Church for an assumed genocide—well before a proper investigation was possible. Is it wrong to think that Canadians deserve better?

What it Takes to Prove a Genocide

In chapter 3, retired professor Hymie Rubenstein sets out to rebut the charge of a Canadian genocide made manifest by graves at the residential schools.

As he notes, quoting Irwin Cotler, chair of the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, “If we say everything is a genocide, then nothing is a genocide.”

The best part of Rubenstein’s chapter is its treatment of allegations of the forcible transfer of Indigenous children to residential schools. Any such forcible transfer would fulfill the fifth element of the United Nations 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.

He begins by quoting from the Convention’s formal post-1948 commentary:

To constitute genocide, there must be a proven intent on the part of the perpetrators to physically destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group. Cultural destruction does not suffice.

He then demonstrates (as others have) that at no time did even close to a majority of Indigenous children ever attend the residential schools, as would seem to be a prerequisite to achieving genocide in fact.

But even more compelling is Rubenstein’s treatment of the required mental intent with respect to forcible transfer. He refers to the legislative history of the Indian Act, showing that attendance at residential school per se was never legally compulsory. Lack of legislative compulsion is key in demonstrating the government’s lack of an intention to cause genocide through forced removal of children. In fact, it is a complete answer. That remains true even if geography, poverty, family malfunction or truancy may, in fact, have compelled attendance in many individual cases.

In Chapter 8, Michael Melanson builds on Rubenstein’s earlier chapter with a helpful analysis of what formal (i.e. unqualified) genocide actually entails under the 1948 UN Convention.

Melanson deals one by one with the various headings of genocide as described by the Convention: homicide; causing serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately causing physical destruction, forced sterilization, and forcible transfer of children. I only wish space allowed for a description of his arguments. The points he makes are quite compelling.

I think Rubenstein is better on the forcible transfer point, but let’s allow Melanson the last word overall: “Canada [he says] has brought into the world the concept of non-criminal, uncorroborated genocide” and is threatening to criminalize those who deny that characterization of what happened. Strange indeed.

Residential Schools Were Really Not That Bad

One of the arguments of fact made by our authors against the charge of genocide is that residential schools were actually a good experience for a great many of the children who attended, and in addition they produced many success stories.

Chapter 12 by the pseudonymous Pim Wiebel is a veritable panegyric on the benefits of attending residential school. The chapter draws heavily on the positive points made in the annual reports of the Department of Indian Affairs—hardly an independent and disinterested source.

Chapter 14, by Professor Ian Gentles, follows much the same lines. He asserts that residential schools “were actually in the forefront of the battle to reduce childhood mortality” and to combat TB brought in by the children from the reserves. He takes issue with allegations of poor food and inadequate nutrition. He points to little or no drug and alcohol abuse at the schools, unlike back on the reserves. [280-282] He argues that the frequency of sexual abuse has been overstated. He then reports on the benefits of extracurricular activities, under headings like “The Fun We Had at Treaty Time;” “Sledding;” “A Long Sleigh Ride;” Hockey and Skating;” “The New Radio and Record Player in the Girls’ Room;” “Hunting with Sling Shots.”4

Some or all of Gentles’s points may well be literally true, but he surely cannot think they tell the whole story.

Then there are the testimonials from eminent graduates. These are also quoted in various other chapters in this book, with a testimonial from Rodney A. Clifton comprising its entire final chapter.

As described by Wiebel and Gentles and in the testimonials, it all sounds quite idyllic: much better than life on the reserves, better than life of local non-Indigenous children, better than it was at my own private boarding school in the early 1970s. One wonders why anyone ever ran away from the residential schools.

On reflection, it is a mistake to treat the residential school experience monolithically—to suggest it was essentially the same for everyone, at every school, down through the years. Both the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report and this book make that mistake. Of course, there were success stories. Also, for many students, the schools were not completely bad. Yet undeniably, for many others, it was a shattering experience. Incidents of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse were well documented. There were disappearances and there were deaths.

History is never simple and nor is the truth. The sooner everyone steps away from the rhetoric of genocide on the one hand and benign paternalism on the other, the better in terms of healing those who feel they need it, and their reconciliation with those whom they feel were responsible. Saying that intergenerational trauma does not exist—that it has no real basis to exist—does not make it simply go away.

Following the Science

Chapter 13, entitled “Everybody’s Favorite Dead White Male,” describes the background and personality of Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, the supposed government whistleblower on health care issues at the early residential schools.

As chapter author Greg Piasetzki demonstrates, Bryce was very much a man of his times and motivated by his own preoccupations. What Bryce really thought and did makes him an unlikely hero in the residential school story for those who would at the same time tear down the reputations and statues of others like John A. Macdonald or Egerton Ryerson.

We also have Chapter 16, entitled “The Tainted Milk Mystery,” persuasively debunking the narrative of government experiments with the health of select residential school students.

At issue were double blind studies in which select children got extra vitamins and others did not. That is hardly in the realm of Dr. Mengele, even given the lack of Indigenous parents’ informed consent to their children’s participation.

I hazard that the real reason for the studies was quite mundane, but nevertheless troubling. They were likely an attempt by the Department of Indian Affairs to protect its annual budget by not wasting money on the health of the children in giving them extra vitamins unless and until doing so had been proven worthwhile.

The Knowledge Keepers Have an Agenda

Dr. Frances Widdowson’s Chapter 5 relates the various elements of the counter narrative, with specific focus on an alleged lack of credibility in the “tellings” of the Tk’emlups Knowledge Keepers.

In fairness, her coverage of those elements is more persuasive than elsewhere in this book.

As for her specific focus, she says that the Knowledge Keepers “pretend to believe things that are highly unlikely to be true.”

She says their doing so is “part of the wider rent-seeking efforts that rely upon characterizing Canada as a perpetuator of genocide.” [emphasis added]

She further suggests that the Knowledge Keepers and their friends and relations have shaped the narrative for personal gain:

…[that] funding billions of dollars [based] on the allegations of unmarked graves … only benefits a tiny elite of Indigenous and non-Indigenous rent-seekers to the detriment of ordinary Indigenous people.

Widdowson thus makes it personal. She does so based in part on some of the Knowledge Keepers having the same last name as one of Kevin Annett’s informants respecting the supposed murders; and in part through other circumstantial innuendo.

At law, there is a presumption of regularity in the administration of public affairs. Allegations of bad faith must be supported by irrefutable evidence. The lack of irrefutable evidence here makes Widdowson’s allegations irresponsible and offensive. It also tends to discredit the rest of her arguments, as well as the arguments of those who ride with her. It is clearly she and her fellow travellers who have the agenda.

*

Conrad Black supplied the preface to this book. He calls it “profoundly needed for the restoration of sobriety in public discourse ….”

Black is a Canadian patriot in the American sense of the word. He is entitled to his views as such, and he very much enjoys expressing them.

Lord Black has a particular fondness for adjectives. Never use one where three will do. The more provocative the better.

That habit is hardly conducive to sober public discourse.

But more pertinent to the book under review, Black also evidently fails to appreciate that piling on adjectives only persuades readers who are already persuaded.

A reader’s appreciation of this book will depend largely on what he or she wants to take from it:

- Readers who already embrace the counter narrative will be glad to have a compendium of points to use in persuading their friends: “See, I told you so.”

- Readers who cling to what Paulette Regan terms the Canadian “peacemaker myth”5 in its historical relations with Indigenous people will find some comfort here.

- Readers who have wondered about specific aspects of the narrative, such as the history of the Kamloops orchard, the media backstory, Dr. Bryce or the alleged experiments with tainted milk, will appreciate the care and balance with which those issues are explored in this book.

- Survivors of residential school trauma will be confused and saddened by this profoundly different version of what the schools were really like and what those who attended them really experienced.

- Friends and family of survivors will be enraged on their behalf.

- So will those who brand anyone with anything good to say about residential schools as “genocide deniers.”

However—like Lord Black’s adjectives—this book is not going to change anyone’s mind about anything. Rather, it will only harden positions.

In the final analysis, Grave Error adds nothing to an understanding of truth and stands directly in the way of widespread reconciliation.6 It primarily serves as a warning of the collateral damage that can be done in the war between narrative and counter-narrative. All of which is such a pity in an area of public discourse where, as Lord Black says with unconscious irony, restored sobriety and greater balance are both so sorely needed.

*

Richard Butler is a latter-day settler living on the traditional territory of the lekwungen-speaking Peoples, a retired lawyer and sometime law professor, and more recently a writer on various Indigenous subjects. He is the author of Taking Reconciliation Personally & I Dare Say… Conversations with Indigeneity, published through A & R Publishing, and recently reviewed the published work of Aaron A.M. Ross for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

- A more fulsome version of this review will be included in my forthcoming book Things that Needed Saying at the Time which, when completed, will be published on Amazon. ↩︎

- As Widdowson notes, Annett also once asserted that Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip visited the Kamloops Indian Residential School in the 1960s and took some children on a picnic—who never returned from it and have not been seen since. ↩︎

- The Tk’emlups leadership now seems to have taken a first step in that regard. It remains to be seen whether other Indigenous leaders will follow. See Terry Glavin, June, 2024 https://nationalpost.com/opinion/terry-glavin-kamloops-first-nation-puts-even-more-distance-from-mass-grave-claim ↩︎

- The TRC report may indeed have only provided one side of the story; but have these folks not read Shingwauk’s Vision, J.R. Miller’s balanced and harrowing account of life at the residential schools? ↩︎

- See Paulette Regan, Unsettling the Settler Within: Indian Residential Schools, Truth Telling, and Reconciliation in Canada, UBC Press 2010. ↩︎

- The same can be said of books like Michelle Good’s Truth Telling: Seven Conversations about Indigenous Life in Canada, reviewed recently in BC Review. Good’s book makes bold assertions of genocide without any evidence supporting genocidal intent. ↩︎

19 comments on “This is a worrying book”

Mr. Butler tells us that he is worried that the book is not perfect and that disturbs him because he suggests that it may be used in a negative fashion..

However, this book is in response to a purely irresponsible action which was to make a large public announcement with the scantiest of proofs, then to prevent a proper examination and finally to take a large sum of money and not provide any further information. The feeling of the people who worked in these schools, many of them indigenous have had their feelings completely ignored.

About $12 million public dollars have been poured in to the Kamloops leadership with absolutely no reports coming back.

Maybe Mr. Butler is correct that the book won’t change anyone’s mind. I am not as cynical as him as I have some hope that some readers may even be provoked to learn more about the subject.

However, it certainly provides a warning for our weasily politicians and media not to go crazy at what is basically a rumor. The flag at half mast for months, our international reputation besmirched, loss of trust in governments who start forcing false history in schools, the list goes on.

“Grave Error adds nothing to an understanding of truth and stands directly in the way of widespread reconciliation”

just one example of you contradicting yourself

“On reflection, it is a mistake to treat the residential school experience monolithically—to suggest it was essentially the same for everyone, at every school, down through the years.”

When I saw the cover of the book I saw my cousins and friends, and I wondered if they had granted permission to have their pictures on the cover of such a book? They were students at KIRS. I want to know if they were contacted. I know some of them are deceased. Please inform me. I must say I’m very disgusted by all the lawyers, authors, etc., making big bucks from our pain. Gowling law firm got 56 million for overseeing Indian Day School settlement. I got a cheque of $10,000 sent by Deloitte Touche. Stop making money from our pain! You all have no idea that your research is from your head, not from your spirit. I am a very angry elder. I am hurt more by all these authors, journalists, the Pope, and First Nation chiefs saying they are making things better. They just profit from the pain of colonization. I was hurt very very badly and just want to forget it. Stop making money and granting Indigenous degrees about my pain and that of others who are not here to speak. Giving millions to lawyers for legal fees doesn’t fix it. They get rich and I stay poor and am supposed to feel better cuz I got 10,000?

Tom Flanagan, Widdowson, Black books and newspapers bonfire will take place on September 30.

Before then see MP Leah Gazan’s Private Member’s Bill ~~ focus: federal Indian Residential School deniers.

Waving from Treaty Six in Saskatoon Saskatchewan.

The deniers all seem to be on your side. We just seek the truth while you engage in evidence destruction and book burning. Isn’t that a fascist tactic?

Perhaps Frances Widdowson should enjoy her 15 minutes of fame, as she apparently did not get enough attention when she was fired from Mount Royal University. Butler’s review of her chapter concluded that she provides little more than innuendo herself. Read this again:

“Allegations of bad faith must be supported by irrefutable evidence. The lack of irrefutable evidence here makes Widdowson’s allegations irresponsible and offensive. It also tends to discredit the rest of her arguments, as well as the arguments of those who ride with her. It is clearly she and her fellow travellers who have the agenda.”

Enough said.

Mr. Butler’s review has not refuted the claim repeated in several articles that there are no hidden grave discoveries. His accusations of author innuendo distract us from the evidence and inconvenient facts provided as counter arguments to the desire that there are unmarked graves. Shouldn’t incontrovertible truth based on verifiable facts be the main goal? The history of residential schools is another story that might be called the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Is history without political intervention possible?

“Unmarked graves” indeed carries the innuendo of death by foul play. The best response is to point out the complete lack of evidence of graves or murders. This book does so unrelentingly.

Yet there is equally no evidence that Indigenous leaders “desire” for graves to be found stems not from the need for answers but from “rent seeking” for personal gain. That counter innuendo is rightly considered false and malicious until clear evidence of malfeasance is forthcoming. This book provides no such evidence.

Except, of course when referencing a Hollywood film for the sake of emphasis-be careful. This entire debacle is about the evidence(physical and oral), the bad and the ugly. There is no good in any of this history apart from learning from our mistakes.

This is a decent review although I disagree with the author that no viewpoints will be changed by it. I know of a few cases already that suggest otherwise. But I think the book very much provides the documentation that is required at this moment. I don’t agree with everything everyone writes in the collection, and I agree that some contrary views would have been useful (confirming the “wickedness” of the schools, perhaps?). But I disagree that too many here deal with innuendo and insufficient evidence. We know that huge sums of money had flowed with virtually no strings attached. Still, what are the motivations of those telling tall tales, even now at this late date, without evidence of graves? Money, falling in line with an ideology, solidarity? I tracked the references to bad things that did go on in the Indian Residential Schools and found over 30 separate segments in Grave Error. Almost all the authors made such comments. So this wasn’t a love-fest for Indian Residential Schools. We won’t have the full story until the excavations happen. We should expect a severe public reaction then, and one I would guess that is consistent with what is written in this book.

A superb point-by-point review, mostly complimentary to the authors of the various essays, and then ruined by the final paragraph which says, “…Grave Error adds nothing to the understanding of truth…”. That’s the whole point of the book! And yes, perhaps there is some innuendo in the essays, but that is counter to the vast excess of innuendo about unmarked graves and missing children. One example of innuendo on the part of the various authors is a reference to “100 Christian churches burned to the ground or vandalized,” or words to that effect. OK — how many were burnt to the ground and how many had one rock thrown through a window?

In “The History of the Kamloops Apple Orchard” Mr. Butler refers to “the findings of anthropologist Dr. Sarah Beaulieu of possible children’s graves.” There is at least one quote from her in the book where she refers to the disturbed ground as “probable graves.” Now this may have been a one-time slip on her part — there’s no real context for the quote — but no responsible researcher, with the information she had available, would have used any term other than “possible” (and even then may have added an “unlikely”).

Anyway, I will recommend to friends that they read this review — it provides a good summary of the content of the various articles.

Right. I recall thinking “nothing” should be amended to “little” but somehow that didn’t make it into the final version of this.

A courageous review of a political hot potato that is unlikely to please either side. Identity politics, like people in uniforms and red caps are not interested in democracy and tolerance. This is a breath of fresh air in stifling times.

My father, a lawyer who made every dinner table conversation into an episode in the family court of public opinion, regularly reminded us to “consider the source.”

Seems a convenient partisan way to not consider the contents.

Judging by the writer’s bio is all that’s need to understand how this review will be handled. He’s already conceded ownership of his own piece land. Laughable.

Wow. Hats off to Richard Butler for tackling what must have been a very challenging review. He left this reader with the impression that his treatment of this highly partisan account of a brutally divisive issue has, somehow, been remarkably even-handed. Oh dear, too many adjectives (and adverbs). Thank you.

PS: What’s a “latter day settler”? Sounds almost like an offshoot of the Mormons. — Howard Stewart, Denman Island