‘Rich, provocative, awakening’

Numinous Seditions: Interiority and Climate Change

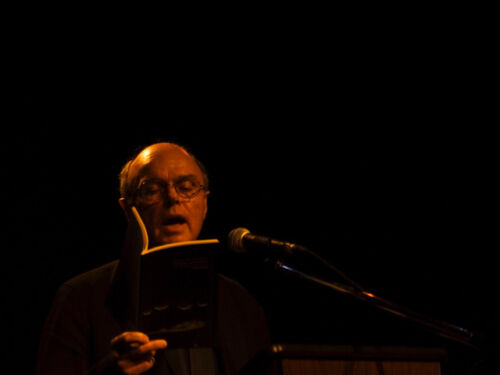

by Tim Lilburn

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2023

$29.99 / 9781772127102

Reviewed by Steven Ross Smith

*

The first semantic gesture one encounters on this book’s arrival – Tim Lilburn’s fourth collection of essays – is, of course the title. It aptly sets up and challenges our comprehension. Numinous, an adjective, means arousing spiritual or religious emotion; mysterious or awe-inspiring; or appealing to aesthetic sensibility. Sedition, a noun, names overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order.

Lilburn, a gentle, intelligent, rebel-combatant brings these two seemingly disparate terms together to set the stage for his complex contemplation of spirituality (a broader scope than simply ‘religion’) and interiority, set alongside and within climate, ecology, politics, “[c]apitalism and colonial hauteur”.

In his preface he writes: “We are entering a new time, a changed climatic and cultural surround, and we don’t, at the moment, know how to move in it […] where to go to learn how to be […] most of us locked in a stasis of stunned amazement.” Indeed, when we hear ‘the news’ and begin to list – pandemic, weather extremes, ocean acidification, accelerated species extinction, collapse of fish stocks, drought, wildfires, heat spikes, flooding, war, and infrastructure collapse – the bewilderment –helplessness, anxiety, and dread sets in.

Lilburn says he is “not a scholar […] but as I like to think, a panic-struck citizen who happens to have a library card.” Some library. Lilburn lists his readings in the endnotes, citing over one hundred texts – Addas to Zwicky. To “learn how to be” he reaches, through that wide reading and meditative contemplation, as the back-note says, to “Platonic, Islamic, Christian, and Zoharic forms” – to teachers, mystics, philosophers, thinkers, and religious figures – from Teresa of Avila, Thomas Aquinas, to Hegel, Hannah Arendt, Thomas Merton, and many more. These provoke a creative and original weave of connections wherein Lilburn posits a path.

He moves from Plato’s Athens Academy in 529 to his own dreams in Covid’s onset in early 2020 and touches on indigenous modes and the exposure of residential school trauma in Canada. He recalls formative conversations as a teenager, with his mother, whom he acknowledges several times, though does not name.

A reader, such as I, not deeply familiar with theological or philosophical vocabulary will flip to the book’s glossary, Google, dictionaries, or contextuality, to comprehend terms such as autochthonicity (indigeneity), catanyxis (shock, piercing), and haecceitas (thisness). However, despite the reader’s semantic learning curve, to Lilburn’s credit, the logic of his exposition, and his ‘argument’ comes clear, and for the engaged reader, it will be, I think, effective and deeply convincing.

In twelve diverse chapters and a coda, Lilburn ranges through and within a varied landscape of contemplation. He creates an argument for beingness that has the possibility of healing humankind’s current dissociation from intuition, knowledge, spirit, self, and nature. However, he notes: “The interiority appropriate to a catastrophe of such magnitude does not lie within the bounds of our current imagination.” So, he becomes our guide, searching for the new, grounding, authentic habitude. The path is individual, and, though it seems impossible, if adopted universally, might offer a way to navigate in and on the hurtling, combusting vehicle we ride.

The first chapters address the shocks we are facing, and whether it is even possible to respond. He considers artmaking, prayer, academia, technology, and capital. Lilburn seeks – his sedition – a “refusal to engage with such meta-worlds, [faith in technological advance, economic evolutionism, etc.] which are ways of evading the full novel sorrow arising from extinctions and extreme weather.” He imagines “an extensive maieutics, [teaching principles and methods] coming from the ancient and the medieval world, a rich part of the Western sapiential tradition, that can help us take up the spirito-political work ahead.”

If I may simplify Lilburn’s argument – in a sense offered as conversations – it is that through interiority – which may embrace meditation, prayer, mindfulness, alertness, attending, absorbing, understanding (and I’ll add ‘humility’) – we can discover, on an instinctive level, our true connection to ‘nature’, a seeing and being seen (even naming “nature” here seems to me to separate); nature, as Lilburn observes, is us. “Here is where the expanding, retrieved, apokatastatic soul, hastened by a variety of maieutic gestures, turns to the world as home and terminus of care.” The basis for his hypothesis and its development is set. Indeed, a home requires care in all its meanings.

The chapter “Contemplative Practices, Contemplative Pedagogies” takes a practical tack and is based on Lilburn’s lecture series presented at Middlebury College in Vermont in 2018, where he also team-taught for a semester. It imparts his vision of the way post-secondary teachers can use a contemplative approach, begun in themselves, then passed to students, to enhance what he calls “transformative learning.” It matters to Lilburn that young, forming minds be stirred. He has long been an instructor of creative writing in universities in Saskatoon and region and in Victoria, where he’s been a knowing and insightful inhabitant of classrooms, with a deeply mindful understanding of the process of animating students or at the very least, endeavouring to do so. He offers plausible scenarios of teacher-student interaction, to demonstrate the way contemplative or meditational practices can enhance learning; he even suggests exercises that can be offered to students, a lectio notebook, a reading-writing practice,to shape a deepening self-connection and eros – which Lilburn describes as a force that “manifests itself as a distinctive voice, an idiosyncratic emotional tone and a signature way of using language.” His proposals are grounded in references from Socrates to the indigenous WSÁNEĆ people of the islands in the Salish Sea.

Through the midsection of the book, the author, a notable poet himself, draws our attention more thoroughly to points raised and to closer examination of the poets, mystics, and thinkers – humans who have sought, in their various ways and disciplines, a deeper intimacy with self and with our blue and browning planet, with ways of treating our “disabling loneliness” or our “outpourings of rage.” A whole chapter is given to the contemplation of poetry’s engagement with philosophy. There and throughout he cites and quotes poets – Rumi, Blake, Anne Szumigalski, Don Domanski, Peter O’Leary, among others. One whole chapter is a reflection on the writing of 13th century mystic-philosopher Ibn ‘Arabi.

As I read through, it seems to me that every page deserves response, and in my copy so many sentences and sections are underlined that there is a temptation just to keep citing and quoting, but of course transcribing the book is not appropriate, nor is it a ‘review’. I must leave discoveries to the reader.

I admire the way Lilburn has woven modes – density to porosity, abstract to concrete, philosophical to personal. Speaking of personal, Lilburn looks inward to confess his own disquiet: “I’ve tasted too acedia’s daily blunting frenzy: who am I; how shall I be in this turmoil and defeat?” Acedia – listlessness, torpor, which he calls “the engine room mood of consumer life” – is a propellant to distractive, escapist behaviour. He sees its manifestations everywhere – social media, professional sports, and popular culture. I also think of bucket lists, stock market speculation, and retail excursions.

A reader might expect proselytizing, and that philosophy, theology, and environment will be dry and perhaps abstract; I found the personal and descriptive matter to be fresh and vivid. For example, Lilburn posits a consideration of Francis of Assisi’s “Poverty in all its forms […] Francis’s poverty is emotional and epistemological as well as material.” It is a way “to know and be nourished.” To illustrate this, Lilburn becomes cinematic: “The small band of the earliest friars made their way to the valley of Spoleto; as night fell, they found themselves in an isolated spot. They realized they had no food with them when ‘suddenly a man appeared carrying bread in his hand…’”. Through such scene-setting, a technique Lilburn uses elsewhere in the book, the reader becomes intimately and presently engaged.

Not only might dwelling inward and recognizing our place on this wondrous globe help us face and deal with our often buried or blurred anxiety, fear, and sorrow, it might help us find some faith and right action; Lilburn suggests it may show us the divine. He is after all a seeker of the spiritual, symbolized as God, but also as divine light. Lilburn proclaims the need to be selfless, to be with, to “feed yourself to the practice of noticing, of being drawn to essential light in things […] what is wild speaks, what is outside speaks, voice angled, under certain ascetical conditions, to our release and benefit. […] This is the political spectacle of contemplative virtues surfacing in the world as communion. Such behavior is our deepest loyalty.” And might I add, our necessity.

Numinous Seditions is rich, provocative, awakening, and it lingers, its light brightening and shadowing engaged readers’ thoughts and emotions, perhaps shifting our attentions, our behaviours, our very essence, and hence our hope. Lilburn adds a distinct voice to the many calling us to truly awaken.

*

Steven Ross Smith, Banff Poet Laureate, 2018-21, loves music, walks on beaches, and is fascinated by moss. His work often juxtaposes disparate threads, as in his poetic seven-book series fluttertongue. He’s been effective too as a literary activist, on behalf of writers—speaking, teaching, organizing, collaborating, editing, presenting, and writing journalistic pieces on literary and visual art. His fourteenth book is Glimmer: Short Fictions, from Radiant Press, 2022. He recently published two chapbooks with Saskatchewan’s Jackpine Press. Newest to appear, in 2024, is The Green Rose, a collaboration with Phil Hall, as a chapbook from above/ground press in Ottawa. Over many years Smith has migrated westward from Toronto and now lives and writes in Victoria, BC.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “‘Rich, provocative, awakening’”

I wasn’t really interested in this book— OMG — what does the title mean????

However Steven Ross Smith’s review is outstanding and sparked my interest — Now a definite read!