Chainsaw memories

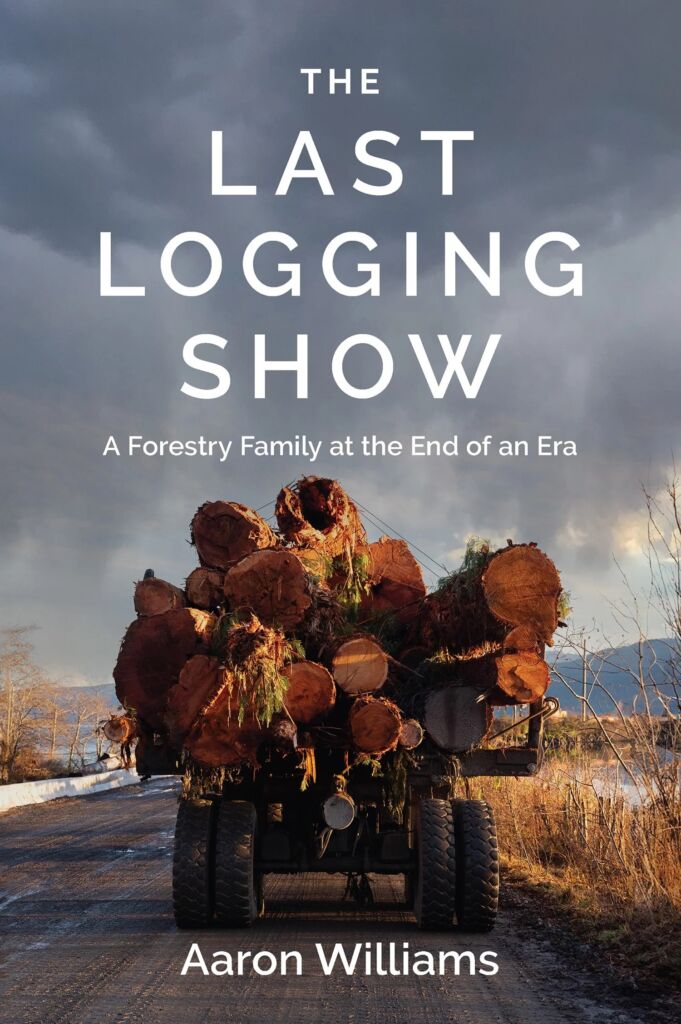

The Last Logging Show: A Forestry Family at the End of an Era

by Aaron Williams

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2024

$24.95 / 9781990776618

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Memoirs seem to proliferate these days with detailed stories of growing up in remote regions of BC, of hiking wilderness trails, fishing the high seas, or scaling old-growth trees, chainsaw in hand. One wonders if marketing specialists have advised publishers that memoirs are “in.”

The good news is that the memoirs are not all about famous people. In fact, this one is about a working-class kid who is grappling with the forestry industry’s contradictions as he traces his family’s involvement and his own questioning of the sustainability of logging the forests of Haida Gwaii, the islands above Vancouver Island.

Aaron Williams was raised in logging camps in BC with an old-time logger for a father and a supportive mother and logging Grandmother Joy doing the raising. He makes good use of his youthful memories to tell us in first-person present tense the workings of various operations that make up the industry.

His years away from the logging world have given him new skills as a writer and he effectively describes the many workplaces that make up logging on Haida Gwaii. He also bears witness to the land debates at public forums between the white logging firms and the Haida First Nation.

Williams, who visits his parents in between stints at high school and later university on the east coast, takes us on his travels to the different work crews performing special tasks to get the logs to market. These are tough jobs, requiring skills without which a worker may not make it safely to the end of a shift.

He has a literary bent that makes the text come alive at times. Some turns of phrase and his unerring definition of terms are helpful. Planes “grope for pavement.” “The sea has a strange chocolate milk hue.” “An eagle near the end of the runway tears at the carcass of something.”

Then there’s this: “A young deer approaches the creek, nibbling at the ground. At first I have an inexplicably strong desire to see it drink . . . The fawn continues down the creek draw with that frustrating lack of urgency wild animals have. I stay hidden. The snapping branches get closer. As they do, a new thought takes shape: I could spear tackle this fawn. Kill it. Eat it. The thought, rooted in some primitive survival instinct, is a less savoury manifestation of oneness with nature.” This suggests Williams’s dilemma in Haida Gwaii: natural beauty over his family’s survival.

Williams also lends his writing talent to the more mundane. A log “processor,” “grapple yarder,” “landing bucker,” “hoe chucker,” and “designated faller” all have stories attached to them. The operators that populate Williams’s account add colour to the forest workplace.

There’s Jarvis Jarvis, the processor operator. He instructs Williams on processing “saw logs” and identifying which logs will go to which markets. Then there’s Dave Unsworth. He runs a log-barged tug that used to be called Captain Bob. “I step onto the Captain Bob and feel some ancient longing fulfilled,” Williams recalls. As with other remembrances, he brings a personal feel to the various encounters.

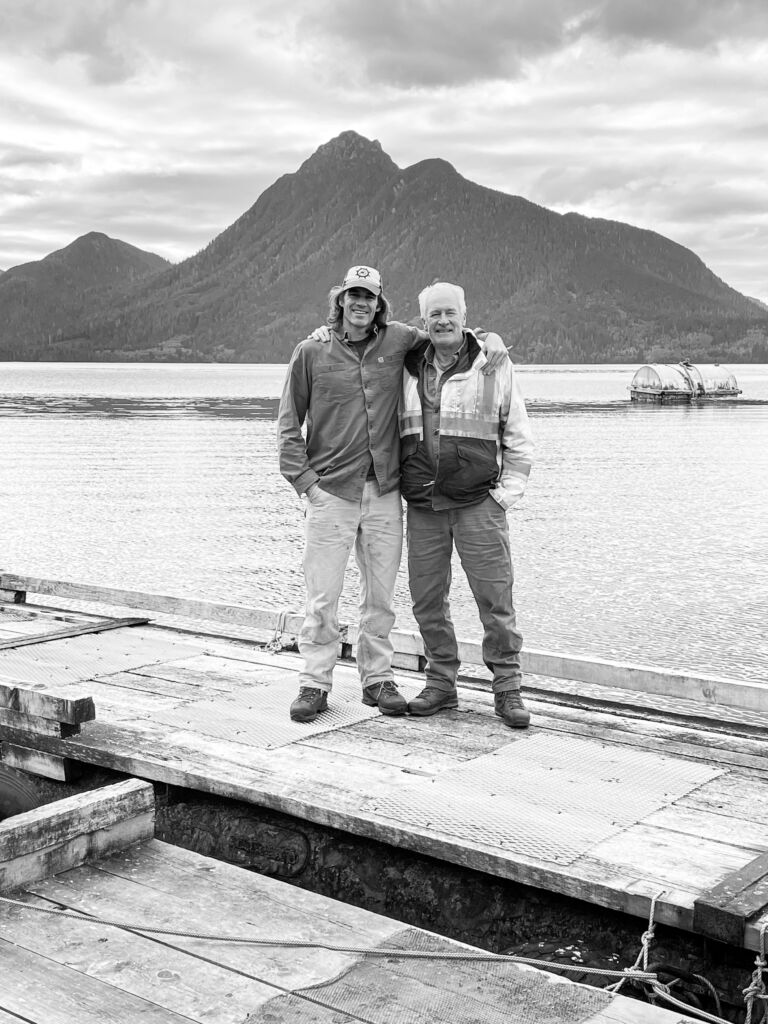

Finally, among the many personalities we meet is Kelly Williams, father of the author. He was a faller employed by Husby Forest Products, one of the logging firms on the islands. His experience in the forest is widely respected. He is also caught between logging as an industry and the objections of the Haida First Nation.

“Dad’s use of the term ‘indigenous rights’ is curious too. In our evolution of language around these events – ‘land protection’ not ‘cutting down trees’ – Dad has a funny way of internalizing and regurgitating such phrases,” he notes. “He knows them all and uses them interchangeably, pairing the modern with the archaic.”

If there is an arc to this story, it peaks around the Haida “Blockades” when the Haida dug in to prevent logging of forests that the indigenous people deemed historically and culturally important. Old-growth cedar, for example, was used for tribal totems and canoes. The eventual result was the creation of Gwaii Haanas National Park and the preserving of Moresby Island.

Williams is careful here to explain the details of the blockades and future confrontations without expressing a strong bias. In fact, he shows an understanding of both sides – the loggers wanting to make a living and the Haida wanting control of their land and its uses. But the blockades spell the end of his family’s way of life and he weighs the plusses and minuses of its demise.

He helpfully adds his observations of the Haida belief system, the spiritual idea that everything is connected. As he notes, “It took only fifteen minutes of lonely running in the deep woods to go from a secular Western understanding of the world to making an easy peace with my cosmic insignificance.” He inserts several historical descriptions of the land, the implements, the disputes, and the history of the industry and these fill out this record of his very personal journey. Also of interest is his tracking of the technological changes that have influenced logging.

I’m tempted to characterize Williams’s book as a cross between Roderick Haig-Brown’s 1940s novel Timber: A Novel of Pacific Coast Loggers and Ken Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion. Elements of both can be found here, but this is not in the same league nor does it pretend to be. It is not a novel, although Williams is clearly capable to writing one with his creative non-fiction writing education.

This is a work about everyday incidents on and off the job that takes readers to the sawdust and woodchip heart of wilderness logging. Further, Williams delivers much to ponder about the destruction of the natural paradise that is Haida Gwaii. There’s analysis of the industry tucked into the day-to-day travels of the writer on whichever vehicle he allows the reader to join him.

The smells, the sights, the attitudes, the arguments, and the dreams all surface as Williams plays his fly-on-the-wall role as a recorder of life on the edge of both a remote corner of civilization and the changing nature of the industry that provided his family’s living. He is grateful and yet questioning of what that industry will mean to future generations.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer and historian. He has never set foot in a logging camp but did work on a sawmill green chain in his youth. He has recently reviewed books by Michel Drouin, Hetxw’ms Gyetxw (Brett D. Huson), Haley Healey, Keith G. Powell, Geoff Mynett, and John Farrow for The British Columbia Review; he also contributed an essay about trade unionist Harvey Murphy.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “Chainsaw memories”