A town named Redemption

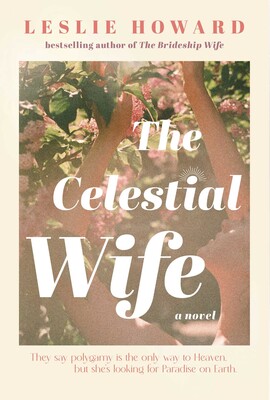

The Celestial Wife

by Leslie Howard

Toronto: Simon & Schuster, 2024

$24.99 / 9781982182403

Reviewed by Caitlin Hicks

*

Historical fiction appeals in particular to a Catholic sense of celestial credit: a good story told about the past, with meticulous attention to detail, so much so that readers ‘get credit’ for an entertaining history lesson. Is this a reason to lean towards, and to love, this genre?

Add a ‘woman scorned’ motif to the entertaining history lesson and you’ll land at The Celestial Wife, the second novel by Vancouver and Okanagan writer Leslie Howard (The Brideship Wife).

Howard’s novel describes Redemption, a community that mirrors the existing BC community of Bountiful. The latter, home of Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, made headlines when its leader was convicted of violating Section 293 of the Canadian Criminal Code, which defines the crime of polygamy.

And yet, justice is not guaranteed just because we think we live in a just society. The fictional community of Redemption is where religious dogma and the good, trusting nature of believers have been warped to form a closed society beyond recognition as any kind of democracy. Instead, thought control of this brand of religion means that every act, every thought, and every explanation of how the world works has been designed to crown its leader with control over the lives of all its men, women and children. In the name of God.

This is a story of personal rebellion against religious sexual slavery. It’s also an account of child trafficking and belief-based sexual abuse; and of the difficulty of enforcing the law when its abrogation is part of the society from which it evolves. The year is 1964.

“Plural marriage, hard work and motherhood are a woman’s greatest glory,” Daisy Shoemaker remembers during a bout of backstory about the Bishop’s unrequited marriage proposal to her mother and her subsequent banishment to a cottage on the outskirts of their community.

With this seemingly arbitrary decision made by the Bishop, Daisy has become an outsider with no agency except beauty and youth. Never mind that her name is Daisy, and that every other female character’s name is spring-pastel-flowery to the point where it’s difficult to imagine any of them as individuals—Brighten, Violet, Hyacinth, Lavender, Tulip, and Rose, to name a few. Whenever another woman enters the frame with one of those names, you imagine the below-the-knee dress, the hair swept up, and the demure obedience. When one addresses the other with “Keep sweet, Daisy,” the greeting underscores the ick factor of this community and so much of its acquiescence to ideas, rules, and regulations that ultimately entrap the women and many of its men for the glory and privilege of a few at the top.

The story begins with Daisy and Brighten, Daisy’s best friend since grade one, both of them sharing the unenviable status of daughters of ‘undeserving men.’ The young women examine, with trepidation, their looming Placement, a yearly event akin to a debutante ball, featuring formal gowns, eligible bachelors, and a chance to meet local royalty.

The big difference: in this polygamous outpost, Placement is a scripted mass wedding ceremony that parades beautiful, young women in the bloom of their youth to an audience of leering, aging men who will be matched up for marriage and all that this implies. The young women wear bridal gowns for their wedding day and will thereafter live in service to their new husbands (most who are not new at all). Men in this group have numerous wives already. And, lest we forget, so many children that they reside in family compounds and need wall charts to remember names, organize chores, meals, school hours, and conjugal visits. These visits consistently result in unreasonably large families sired by one man. Howard also depicts: bunk bed dormitories, huge dining halls, and ample jealousy and catty behaviour among the many wives—obedient breeders that the women have ostensibly agreed to be.

Daisy seems destined to have a more romantic go of this Placement; her crush, Tobias, in cosy favour with Bishop Thorsen, likes her in return. According to last-minute gossip, their coupling looks hopeful. Daisy accepts this choosing to become Tobias’ first wife. Not thinking of the day her first-wife status will be usurped by the next inevitable Placement in a year, Daisy pats Brighten’s hand with an optimistic “Everything’s going to work out fine.”

But of course, it doesn’t work out fine for any of the women, except Daisy’s arch rival Blossom, who in a last minute twist of the Bishop’s arbitrary whim, ends up as Tobias’ wife. When Daisy understands that she must be alone with and become the most recent sexual mate of the balding, pot-bellied Bishop Thorsen, her revulsion is so instant that she vomits in full view of the congregation. That attracts his ire at the ultimate humiliation.

Daisy escapes out a bathroom window with Brighten, who has been promised to the repulsive-sounding Brother Earl. Brighten doesn’t make it outside of Redemption. Howard describes the production line of conjugal visits to seal the wedding promises: rooms designated for the new couples, other sister-wives wiping down sticky surfaces with sanitizer, perfume spraying in preparation for the next couple waiting in line for the conjugal room. Readers will get the picture of mass incarceration for these young women, whose lives are now destined for rote sex at the whim of middle-aged men, pregnancy, child-rearing, and housework.

So, this born-into-slavery seems to be the meaning of this brand of polygamy, but it’s also sold as a spiritual practice. Although Section 293 technically could be argued to infringe on the right to Freedom of Religion under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, in Howard’s novel there is no doubt about the infringement of personal rights and freedoms for the women of the community.

When you acknowledge elements of the larger picture of the abuse of women around the world, it’s not news. But the premise of Redemption is so repulsive that some of the details of this story are almost unbearable, although not unbelievable. It’s a portrait of power and belief gone awry, of wishful thinking of men-as-gods, of the abuse of the idea of so-called religion, and the big and generous hearts of women who get sucked into the mire.

Of course Daisy cannot abandon the community in which she came to life, and after some of the peace, love, and rock ‘n roll events of the Sixties that she experiences on the outside, she goes back inside the community to free her mother. The risk of discovery creates the suspense of the final section of this engaging work of historical fiction.

*

Caitlin Hicks is a BC-based writer and performer. In addition to journalism and reviews, she’s written for stage, film, and radio; her novels include Kennedy Girl and A Theory of Expanded Love. Read more at www.caitlinhicks.com. [Editor’s note: This review is Caitlin’s first for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (nonfiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “A town named Redemption”