‘Different, and set apart’

Standing at the Back Door of Happiness: And How I Unlocked It

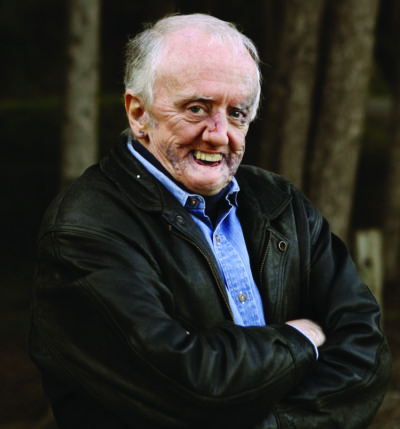

by David Roche

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2024

$22.95 / 9781990776762

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

*

When I was a kid, I had too many teeth. By the time I got braces at eleven, the dentist had removed a whack of them, including one that was growing out of the roof of my mouth. Plus, I had pushed out the front two from sucking on my finger backwards (just couldn’t suck your thumb like a normal kid, could you now?) and they had grown in awkwardly with a gap and one longer than the other.

Which is just to say that although I had nothing like the facial disfigurement that author David Roche has experienced since birth, I can certainly relate to feeling ugly, different, and set apart by my appearance for some years of my life, although my perceived hideousness was eventually rectified by the dental industry and time. David Roche was born with facial vascular malformation which caused his veins to proliferate in an out of control fashion on the left side of his face. Furthermore, he had his “lower lip removed” when he was “fifteen months old” in 1945. As Roche himself describes his book, it is a definite mish-mash of “stories, essays, memoirettes, letters” and other occasional pieces. Although this structural style can feel a bit slap-dash, its willingness to leap between times, moods, and tones ends up being its strength. Reminiscent of Lucy Grealy’s memoir Autobiography of a Face, on her own journey with identity and love after suffering from jaw cancer and its subsequent disfigurements, Roche focuses more on how he found his “incredible gift” for narrative and tangible locations of beauty and joy.

Being born into a large, Catholic, and wholly accepting family indubitably gave him the essential foundation for his later ability to find love, relatability, and transcendence. Roche addresses his childhood, his seminary study, his dozen years of devoted travail for the Democratic Worker’s Party and his discovery he was an alcoholic in semi-linear fashion during the three titular chapters, divided in numbered parts. His single fatherhood is also lovingly described, especially during the chapter called “Camping with Amy” although the reader isn’t told who the mother was nor how Roche became a solo parent. Somehow knowing all the details doesn’t matter so much because the core images are so vivid. For instance, his accounts of holding a job in a dildo factory during the “neodildoic age” when the toys were only the colour of “Bazooka bubble gum,” of his ministry with AIDS patients in which he never shrinks from either the details of their sex lives “strapped in a harness” nor their dying, wearing diapers as big “as something you would see in a cartoon” or of his falling further in love with his wife Marlena during dinner at a Thai restaurant as the “fog [was] rolling in over Twin Peaks.”

Roche has a deep facility with inviting aurality. His voice beckons the reader in, even as they may doubt if they want to even hear about religious perspectives or classroom motivational workshops or his days on a film set or his compulsion to eat fudge.

The most engaging sub-genre for me is Roche’s diaristic chapters. In “How I spent my Christmas Vacation, 2001” he details the days of his prep, surgery, and recovery after a sclerotherapy procedure. He veers between gratitude for seeing loved ones at his bedside and regular morphine doses, and allowing himself distaste for the “metallic” Jell-O and his own “fetid aroma.” In “Love you to Death and How That Works” we are presented with the moving and startling account of a friend’s MAID-assisted demise as people weep and sing Van Morrison songs. All of Roche’s stories are threaded through with compassion, for self and others, as he navigates the always-challenging terrain of coming to terms with love, fear, judgment, mortality, and all the emotional paths a human must walk down.

Although Roche has had to constantly encounter resistance to his own appearance by those who consider him initially repellant, it is this very impasse that enables him to teach and learn and develop more immense layers of empathy. And every time my own cynicism as a reader rose, and I began to find his tone treacly or sentimental, he switched to a seamier descriptor of the underside or slipped in a joke.

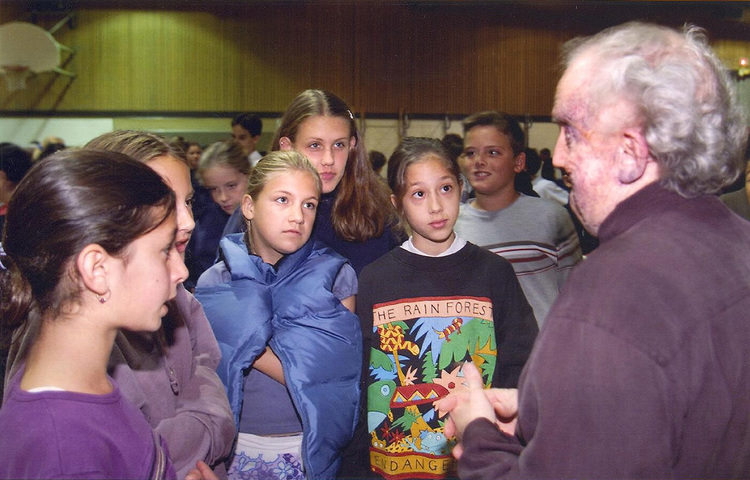

The central emphasis throughout is how storytelling, whether at the Carnegie Center in the DTES or at a Grade Six classroom or even at the White House, is the core of connection, transformation, confidence, and healing. His own list of New Year’s resolutions reminds us that being silly, as in the imperative, “Wear yoga pants that enhance my body parts” as well as simple, like the order to “Sit in the Gumboot café and write” are both essential to being real with efforts towards living the life one truly desires and needs. Roche doesn’t end on a “happily ever after” note but on a short chapter, “Picasso,” where he acknowledges his own momentary difficulty he experienced when he truly looked closely at his appearance for this first time and saw: “A crooked mouth, bulging left cheek, eye too large.” And then, through his own fierce determination to be honest, and within the love of others, how he was thus able to increase his bond with humanity, allowing this reader to stand at her own back door to happiness by putting all forms of disfigurement in perspective and rising above the waste of energy in shame.

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and published at eleven—a short story in a Catholic school’s writing contest chapbook. She gave public poetry readings in her teens; Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction, and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven and Locations of Grief. She also runs Marrow Reviews, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen, and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props, and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. [Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Tom Wayman, Chris Walter, Andrea Warner, Aaron Chapman, Emelia Symington-Fedy, and Sean Kelly for BCR.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “‘Different, and set apart’”

David is our friend, neighbour and inspiration on the Sunshine Coast. Thank you for this beautiful review.

Catherine, I love your reviews! Please keep writing them. You are a natural writer, and your honesty shines on through. I’m now gonna get this book and also source down your writing. More power to you,