Much more than field research

The Wild Horses of the Chilcotin: Their History and Future

by Wayne McCrory

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2023

$39.95 / 9781990776366

Reviewed by Kenneth Favrholdt

*

Marilyn Baptiste, former chief of the Xeni Gwet’in First Nation in the Chilcotin region of British Columbia, opens this remarkable book by stating, “Wayne (McCrory) takes you into the secret world of our Tsilhqot’in people’s wild horses, what we call qiyus or cayuse.” Indeed, McCrory through his well-researched and superbly illustrated book, takes us on a journey through time that combines dreams, legends, and history. “The name Chilcotin comes from the Tsilhqot’in language meaning ‘People of the River or Ochre River,’ referring to the base for paint.” The Tsilhqot’in Nation is home to 450 Dene (Athabascan)-speaking people.

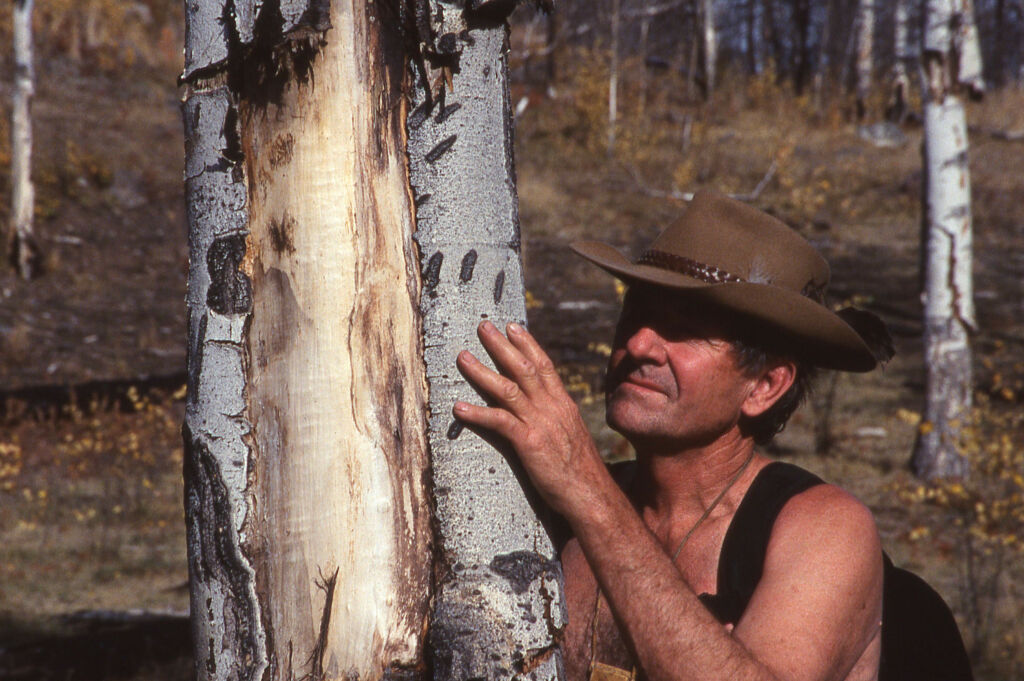

Graduating from the University of British Columbia in 1966 in zoology, McCrory became a wildlife biologist, first studying grizzly bear habitat threatened by clear-cut logging. His work to save the wild horses followed — involving two decades of research. In that span of time, McCrory has published more that 90 scientific reports on wildlife and conservation.

McCrory researched grizzly bears and other wildlife to try to help the Xeni Gwet’in to halt or modify the logging planned for their 770,000-hectare Aboriginal Preserve established in 1989. It is still largely an intact wilderness because of its remoteness. He describes the vast Brittany Triangle, part of the Chilcotin Plateau known as Tach’elach’ed, which was destined for logging up to 62,000 truckloads of lodgepole pine forest.

The Triangle also had a healthy population of “fine-looking wild horses that appeared to have integrated into the natural ecosystem.” This became the focus of McCrory’s interest in the wild horses. In June 2001, while researching grizzly bears in the Brittany Triangle, he dreamt about a magical stone horse.

David Williams, a retired professor who lived in a log cabin in a new provincial park, ran an organization with his wife called Friends of Nemaiah Valley, helping McCrory and Marty Williams conduct field research. At a public meeting, McCrory recommended that the Brittany Triangle be fully protected as Western Canada’s first wild-horse preserve. There were an estimated 1,000 wild horses left in the West Chilcotin in the year 2002, today 3,800.

McCrory argues that the horses, known in Tsilhqot’in culture as qiyus,are “a resilient part of the area’s balanced prey-predator ecosystem that predates the arrival of Europeans to the region.” In 1999, 2,800 wild horses remained in the West Chilcotin area. In 2014, The Supreme Court of Canada confirmed the existence of Aboriginal Title over a portion of Tsilhqot’in territory including part of the wild-horse preserve. That year also saw the rejection of Canada’s largest open-pit mine, Taseko Mines, which would have drained Fish Lake (Teztan Biny). Chief Marilyn Baptiste helped rally support to stop the mine and establish the Indigenous Protection Conservation Area Tribal Park which incorporates a large portion of the wild-horse preserve.

McCrory devotes chapters to stories of the Chilko wildfire and its impact on the horse population, and the ancient relationship between wolves and wild horses and their other predators, mountain lions and bears. Wild horses were an important component of the gray wolf diet but not the other carnivores.

As well as wildfire — and the Tsilqot’ins’ controlled burns — winter was a serious threat to the wild horses. But over four centuries, the Chilcotin wild horse, McCrory states, “has been able to roam free and thrive within a fully functioning predator-prey system.” The horse was a special being, known as nen.

But with the arrival of cattle during the period of the Cariboo gold rush in the late 1850s, ranches took over the grasslands and competition between cattle and wild horses ensued. It is estimated that over 21,000 cattle crossed the American border into B.C. between 1859 and 1868. By 1863, many cattle drovers had discovered the Chilcotin grasslands and white ranchers “had started scapegoating Indigenous horses to cover up range degradation caused largely by their own cattle.” Indian reserves were kept small and consequently the number of wild horses was low. In 1896 the “Act for the Eradication of Wild Horses” made it lawful to kill unbranded wild stallions running at large on public lands.

By 1915, there were 100 ranches and 20,000 head of cattle in the Cariboo-Chilcotin region. An estimated 15,000 wild horses were scattered across the region by 1926. But in the next two decades 10,000 wild horses were killed. By the mid-1960s, McCrory reports, a newly-formed Canadian Wild Horse Society recommended that wild-horse preserves should be established in B.C.

McCrory mentions an article in the Vancouver Sun newspaper by author Terry Glavin who reported on a controversial cull in the winter of 1987-1988. Glavin described how the wild horses were run down by mounted cowboys through the snow that winter. The government’s population estimate of wild horses was contradicted by McCrory’s own assessment that there was no convincing evidence of overpopulation of wild horses. Except for the West Chilcotin, the century-long bounty hunts had finally achieved the government’s goal of wild-horse eradication from B.C. ranges.

After the establishment in 2002 of the new wild-horse preserve, McCrory recounts a speaking engagement which elicited tales from old-time ranchers, mustangers as they were called. “Their stories also brought a human dimension to the cruel history of the Canadian wild-horse bounty-hunt era.” The intersection of Indigenous and settler societies is a discussion McCrory, however, avoids.

The final chapters in McCrory’s book deal with the origins of the Chilcotin wild horse. In 2003, with the Friends of the Nemaiah Valley, a genetic study was launched with the help of Dr. E. Gus Gothran, one of the world’s foremost equine genetic experts of the University of Kentucky. “Genetic studies,” McCrory states, “show two distinct horse populations in the wild-horse preserve. Brittany Triangle horses have Canadian Horse and East Russian (Yakut) ancestry, with some Spanish bloodlines. The rest of the Chilcotin wild horses are descended from Spanish Iberian horses brought to the Americas in the 1500s by the conquistadores.”

McCrory summarizes the theories about the origins of the Chilcotin wild horse: “Horses that escaped from various European and American domestic breeds brought in during the 1858 gold rush followed by early white cattle ranchers; escapee horses from the first European horses brought to the Americas by explorers, primarily the Spanish, then spread by Indigenous tribes across the interior of North America; and survivors of the late Pleistocene Ice Age horses that may have been domesticated long ago by some Indigenous cultures.

The last theory suggest that the Yukon horses (Equus lambei) went extinct about 5,000 years ago but evolved in North America and crossed the Beringia land bridge to Eurasia developing into the horses that then were brought back to North America in the 1600s: that is, the return to North America of a native species.

McCrory admits more research is needed. But First Nations believe in the early appearance of horses since “time immemorial.” Their oral history in combination with genetic science and historical research is the key to the answer of McCrory’s dream.

McCrory states that “the province has yet to recognize the wild-horse preserve created by the Xeni Gwet’in.” He ends the book by stating …” if we destroy the remainder, our society will lose something of the wild spirit that exists in all of us.”

There are several pages of acknowledgements, a list of wild horse groups in Canada, endnotes to the book’s 34 chapters and 300 pages, and an index.

McCrory’s book is a wonderful collage of stories and images. The photographs, both back and white and colour, are exceptional, with captions that provide important descriptions and details. My only complaint, as a geographer, is the map which straddles two pages (248 and 249) doesn’t do justice to the spread of the horse across North America.

McCrory’s best-selling chronicle has won the Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize for Outstanding Scholarly Book on British Columbia for 2024. It is a must-read for anyone interested in horses, of course, and the history of the Indigenous people and their relationship to nature in British Columbia. “The last 2,000 wild horses sill roaming free in the West Chilcotin wilderness and those maintained by First Nations on scattered Indian reserves in BC are cultural reminders of the rich Indigenous equestrian past.”

*

Kenneth Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer, and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, four at the Osoyoos Museum, and he is now Archivist of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press, and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartographica, Cartouche, and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and a commemorative history for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken has undertaken research for several Interior First Nations and is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold rush journal of John Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. He lives in Kamloops. [Editor’s note: Kenneth Favrholdt has recently reviewed books by Michael Hood & Tom Jenkins, Rueben George with Michael Simpson, Jo Chrona, Marc G. Stevenson, George H. S. Duddy, and Terrance N. James for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Much more than field research”