Nature in an ‘epoch permeated by hopelessness’

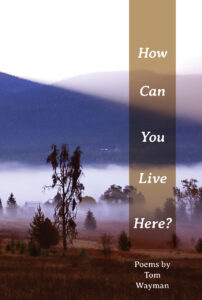

How Can You Live Here?

by Tom Wayman

Okotoks: Frontenac House, 2024

$19.95 / 9781989466698

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

*

When I was first coming into consciousness as a poet in the 1990s, I spent a lot of time around Vancouver’s infamous Commercial Drive, hanging out with cultural creators like Jay Hamburger, Ernest Hekkanen, Maurice Spira, and other movers and shakers who were friends of my much-older-than-me ex-husband.

Around this group of “draft dodgers” and grassroots visionaries, talk of work poetry and work poets swirled regularly and we attended a few readings in 1993 at La Quena Coffee House featuring poets like Tom Wayman, the initiator of the work poetry scene, which included poets like Kate Braid, Sandy Shreve, and a teacher of mine, Calvin Wharton. Their poetry was concerned with acknowledging blue collar jobs, the importance of unions, labour conditions, and other essential facets of holding down employment while still creating art.

Being retired, Wayman (The Order in Which We Do Things) is less compelled by paid work in How Can You Live Here?, and more with focussed on the exigencies, geographies, and mysteries of the remote BC locale in the Selkirk Mountains, where he has lived in for over thirty years.

Each of the book’s five sections—Directions to my House, Terrain Music, The Speed of Time, Contagion in the Countryside, and These Days—are prefaced by an italicized prose piece that attempts to explicate reasons behind the inclusion of the poems within that part. Are these necessary? I wondered at times, as the gathering of pieces is either self-explanatory or the prose summation cannot help but to strain towards inclusivity or consistency where it perhaps doesn’t exist. For instance, the first segment commences by saying it aims to gather, “poems about aspects of a daily life immersed in a natural environment that I find mystifying, enigmatic.” Yet, this statement could very well sum up many of the poems in the book (and certainly much of the subsequent section, Terrain Music.)

I understand the need for division as a form of focus and shaping, but the explications can feel strained or inessential. Conversely, I think I would have loved actual thematic essays between the poems, rather than just these brief prose interludes.

At any rate, Wayman begins by delving into the wind, blooms, snows, birds, stars, and other natural facets of this unyielding environment. Nature poetry is traditionally non-problematized, but Wayman writes an ecological poetry in which knowledge of loss, death, illness, and human impact is prevalent. In “The Bridge,” for instance, he speaks of the continual news of another “friend’s body / sending forth death’s tentative projections / that form, are dissolved for a time, then constitute again / a pitiless crossing into the cold.” Even when writing of the daffodils in the next section, Wayman sees them through a lens not of the innocent but of the ancient, as they return in an “anthem / of bereavement / and resurgence.”

Throughout Why Do You Live Here? Wayman directs our attention to a world that seems familiar and strange too, as with Christine Lowther’s poems that invite us to witness the oceanic and forested realms around her house boat. It’s terrain we are not accustomed to: silences, isolation, distances. The pieces are strongest when the form is thoughtfully considered, as in “Three for the Southern Selkirks” or “Cusp” (and many others) where stanzas or couplets arc down the page in taut tributaries of sound such as within the sliding lines: “forces the high country / at last to lie flat and slow as sand,” or “the storm’s sudden granules of sleet / freezing tight.” I lingered on the image of “first rumours of / ice” from “Return,” the auralities of the “wide / and silent sea” in “Neural Music” (though why isn’t this piece in the Terrain Music section with “Easter Music” rather than in the next segment called The Speed of Time? You see, the prose dividers both explicate and make one question!) and the concept of one’s possessions outliving one in “Clothespins, Books, Teapot.”

Wayman’s collection grows on you. On first reading one might dismiss some of the poems as dull or pedantic due to how they treat of the quotidian aspects of having a house, say (an issue I also face in readings of my new book Moving to Delilah), but on subsequent enterings, one finds the subject matter deepens. Wayman’s poetry is about the real, whether in work or in nature or, as with the fourth section, the pandemic; its aim isn’t fireworks but the slow burn of truth telling. One could become jaded by the urban Covid poem but these pieces are about what it was like in a rural community, again a unique perspective.

Even when in a shopping area, the desolation is more rupturing, as in “Town,” where—

Nobody is entering or leaving the stores

from the empty sidewalks along block after block

of deserted streets. In one gutter,

a rabbit, fur mottled between white and

brownish-grey, sniffs momentarily at

a small mound of a crumpled paper cup

and other debris. The animal, in slow leaping hops,

angles across the pavement toward

an intersection, then

around a building’s corner.

Traffic lights signal to nobody.

While the line break enjambments may be awkward (why end on “and” or “at” or “of” ever?), the subject matter is haunting—the emptiness even more marked by the inclusion of the rabbit that advances towards human detritus and then departs without it signifying much of anything anymore.

Wayman’s repetitions in the final sections are especially resonant: the “I want” in “Quarantine,” “What was it like?” in the imagined interview of “Survey” and the “screen is a mouth” in “The Mouth.” Wayman contrasts, in his final prose preface, the days of yore where many believed that their writing could lead to a “richer life” with today, “an epoch permeated by hopelessness.”

Although I would agree that it seems the arts have more of a struggle than ever to impact on the sorrows and horrors—and to change them for the better—I still think that poets continue to speak and be heard, and that feminist (say, Room) and environmental publications (like The Goose) keep publishing pieces concerned with social justice. How Can You Live Here? is accessible, literal, and often essential writing in lyrical form about the value of living in remote areas, the vitality of other species, and a vision for a more aware and rooted future.

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and published at eleven—a short story in a Catholic school’s writing contest chapbook. She gave public poetry readings in her teens; Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction, and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven and Locations of Grief. She also runs Marrow Reviews, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen, and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props, and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. [Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Chris Walter, Andrea Warner, Aaron Chapman, Emelia Symington-Fedy, Sean Kelly, Jason Schreurs, and Adrienne Fitzpatrick for BCR.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “Nature in an ‘epoch permeated by hopelessness’”