‘The healing nature of writing’

Permission to Land: A Memoir of Loss, Discovery, and Identity

by Judy LeBlanc

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2024

$24.95 / 9781773861357

Reviewed by Mary Ann Moore

*

Judy LeBlanc has written a courageous memoir through interconnected pieces of prose that honour her Scottish and Coast Salish matrilineal heritage. As she researched and discovered her family history, rarely referred to by family members, LeBlanc realized “that not knowing was a coping strategy my family used for two generations.”

The words Louise B. Halfe, Sky Dancer, writes in her poem “āniskōstēw – connecting” which is used as an epigraph to the memoir, help to describe LeBlanc’s writing journey in tribute to the women in her family as a “backward walk.”

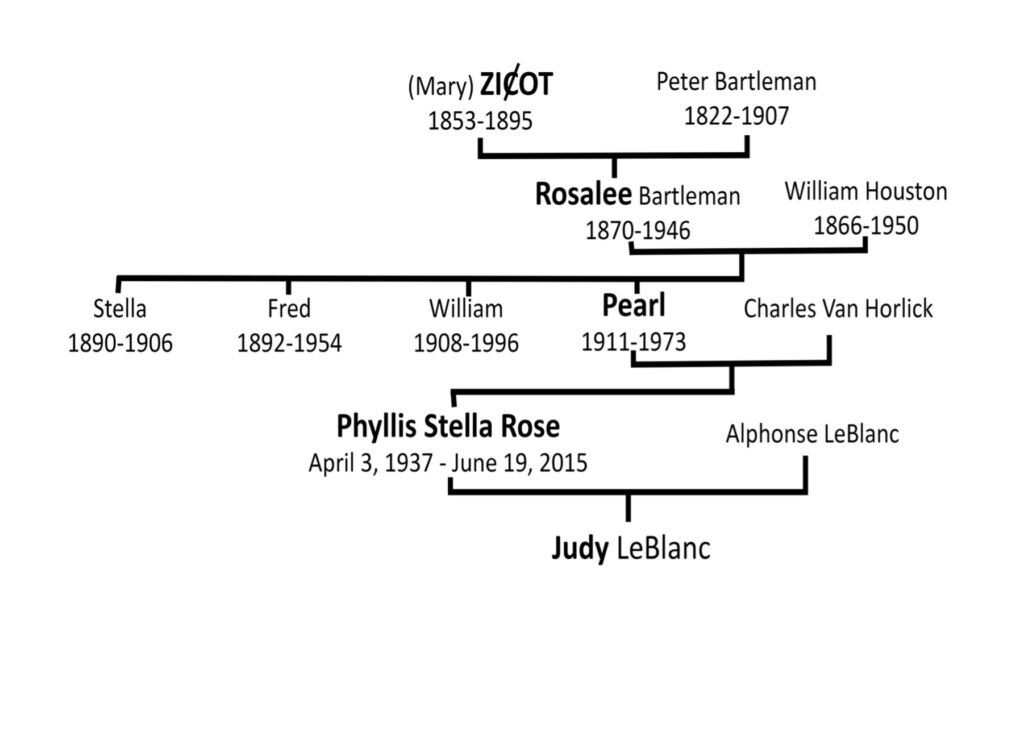

LeBlanc’s great-great grandmother was (Mary) ZIȻOT of the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation who married a Scot named Peter Bartleman. Their daughter, Rosalie, married William Houston “whose mother came from either the Suquamish tribe in Washington or the Tsleil-Waututh Nation from Burrard Inlet in British Columbia.” Rosalie and William’s youngest child of eight was Pearl who with Charles Van Horlick had six children including Phyllis Stella Rose who went by Rose, Judy LeBlanc’s mother. (The cover photograph is one of Rose LeBlanc taken by her husband, the author’s father, Alphonse LeBlanc.)

That’s a lot of names at first but throughout the book, readers will get to know more about these family members through an unfolding story of many parts.

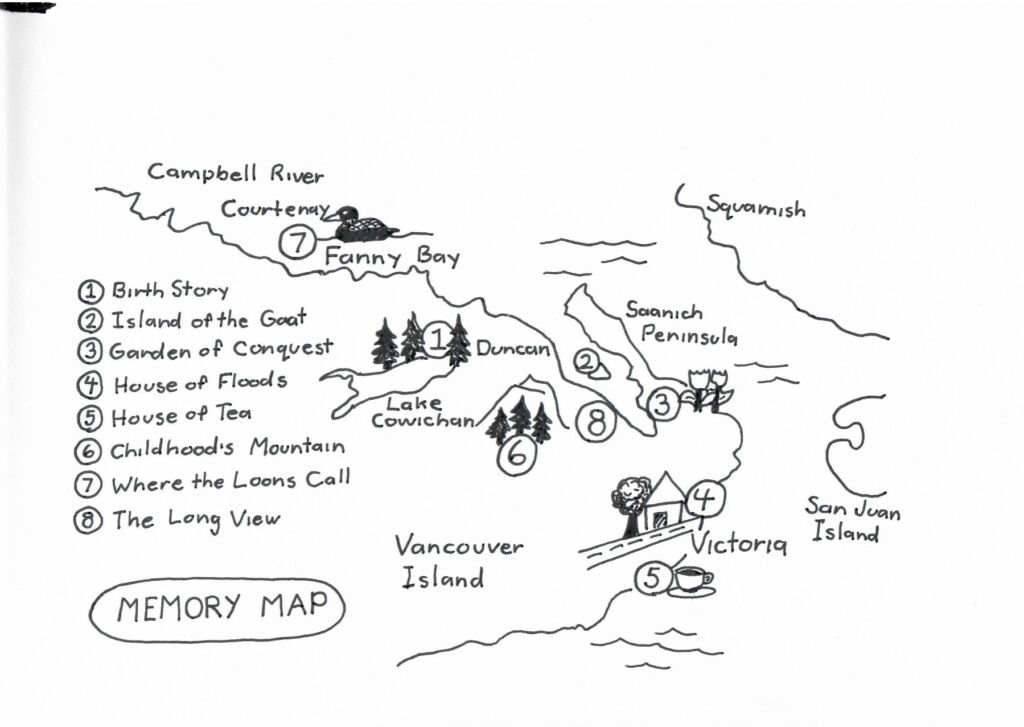

“From Where I Write” opens with a drawing called “Memory Map” of eight places of meaning to LeBlanc including “Birth Story,” (Duncan, where LeBlanc was born); “Island of the Goat,” (in Brentwood Bay, in the Saanich Peninsula, near Victoria); “Where the Loons Call” (Fanny Bay); and “The Long View” (The Malahat).

Short essays, in sub-sections, describe each location such as Island of the Goat which poet Philip Kevin Paul told LeBlanc is SEN,NI,NES (Senanus) in SENĆOŦEN, the language of the Saanich people. In English the name means chest raised up. “Chest in this context means both landable and where the mind is. Therefore, to land is to know from the heart where you are, to have that bond between heart and place.”

LeBlanc spent at least two childhood summers on SEN,NI,NES, her family knowing it was an ancient burial ground for local First Nations people. “Philip Kevin Paul described an additional meaning for chest as pain.”

When she was a child, LeBlanc’s family “didn’t call the First Nations across the water by their SENĆOŦEN, name, nor did we call them First Nations. We called them the ‘Indians on the reserve.’ The reserve we were speaking of is Tsartlip, or W̱JOȽEȽP, meaning in English where the maples grow. Even though my great-grandmother came from W̱JOȽEȽP, this isn’t knowledge that has been passed down to me. I know it only because I’ve googled Saanich place names, which led me to Dave Elliott Senior’s book Saltwater People.”

In the sub-section, “Where the Loons Call,” LeBlanc describes loons as “old souls. They are the oldest living birds having an ancestry dating back thirty to fifty million years.” The loons, who drift close yet “never close that gap between them,” reminds LeBlanc of a lack of communication with her mother. “My interests were not hers. But when she was my age, she transformed a patch of alders and thistle into a garden. I take my family history and transform it into narrative.”

“The Long View” includes a description of a trip LeBlanc took via ferry from Brentwood Bay to Mill Bay and the Tsartlip First Nation. She visits Brenda Bartleman with whom she “shared great-grandparents; her grandfather and my grandmother were siblings.” Bartleman says to LeBlanc: “You are of the ZIȻOT lineage.” LeBlanc repeats the name of her great-great-grandmother until she gets the pronunciation right.

A section of the book of several essays is devoted to Rose LeBlanc, the author’s mother. In the first, “Advice as Bread,” written five years after Rose died, her daughter wrote: “She was brown-skinned, angular, not tall, brown-eyed, with a thick mass of black hair that she kept short . . . People, feeling it necessary to name, said Italian descent, Greek maybe. Possibly Cuban. Never Coast Salish. She rarely spoke of her mother, never her grandmothers on her mother’s side. Never Coast Salish.”

There are missing pieces in the family history as no one knows where Rose was born. “There’s a birth story here lost to my mother and to her daughters, a missed history. A mystery,” says Leblanc in her essay entitled “A Birthday Party.”

In “Election Day,” LeBlanc visits her eighty-five-year-old uncle in Squamish. It’s the first time she sees a photograph of her great-grandmother Rosalie who was born on San Juan Island.

LeBlanc’s grandmother Pearl would have been considered “a ‘half-breed’ with parents who also would have been considered the same. It was understood in the way it is in families that my grandmother folded the half we didn’t talk about into her shadow as if it were a dark-eyed, disgraced daughter.”

In “Place of Rupture,” as memoirists do, LeBlanc uses a combination of intuition and imagination to describe the early life of her great-grandmother Rosalie whose first born was Stella. LeBlanc and her husband visit San Juan Island where Rosalie and William Houston were married in 1889.

In a sub-section titled “Pivot,” LeBlanc writes of the death of Stella Houston, of Roche Harbor, at the age of “16 years, five months, and eleven days.” Stella had gone to an Indian boarding school in Chemawa, Oregon and there contracted consumption which we now know as tuberculosis.

“This wound has festered,” LeBlanc writes after reading the newspaper account online in the San Juan Islander dated August 4, 1906. “My body trembles like a rattle, as if a shadow enters.”

Chemawa is the oldest continually operating Indian boarding school in the United States. Edwin L. Chalcraft, who would have been the superintendent of Chemawa when Stella attended, wrote a memoir titled Assimiliation’s Agent.

In “Epistolary: File #2395,” are painful letters LeBlanc’s great-grandfather and great-grandmother wrote to the superintendent begging him to let their son Fred come home as their daughter Stella “is very low.”

On July 25, 2021, Judy LeBlanc writes her own letter to Edwin L. Chalcraft as if from her great-aunt Stella Houston. This is the healing nature of writing a family narrative: a voice is given to a young woman who was silenced, more than a century after her death.

In the final section of the book, “The Journey,” LeBlanc describes the Tribal Canoe Journeys in which she participated over three summers from 2017 to 2019.

Under No. 9 of “The Ten Rules of the Canoe” titled “A Good Teacher Allows the Student to Learn,” LeBlanc writes that in her third journey, she is invited to paddle “on the day we land at W̱SÁNEĆ, the home of my grandmothers. No one from my lineage or who otherwise knows me waits on the shore. Their absence, I begin to realize, is something I can live with.”

In the title essay, “Permission to Land,” LeBlanc is told by the skipper that she will ask for permission to land on the shore of the Tsawout First Nation. LeBlanc’s not sure what to say but she has been told to speak from her heart and does so. “My great-grandmother came from Saanich, and I’m happy to be here,” is part of her speaking from her heart.

While LeBlanc’s thoughtful memoir is non-linear, and there is much that remains hidden, she has brought her family history into the light. Rough notes may have described her early days of unravelling which then turned into beautifully insightful prose.

LeBlanc writes: “Writing this book has been a personal journey of truth and reconciliation with my Indigenous ancestral past and, at the same time, with my complicity in a colonialist system. Canadians are being called upon to do this work, and it necessary we do it in a way that reflects who we are.”

*

Mary Ann Moore is a poet, writer, and writing mentor who lives on the unceded lands of the Snuneymuxw First Nation in Nanaimo. Her full-length book of poetry is Fishing for Mermaids (Leaf Press, 2014) and she has a new chapbook of poems called Mending (house of appleton). Moore leads writing circles and has two writing resources: Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey (International Association for Journal Writing) and Writing Home: A Whole Life Practice (Flying Mermaids Studio). She writes a blog here. [Editor’s note: Mary Ann Moore has also reviewed books by Kayla Czaga, Christine Lowther, Jude Neale and Nicholas Jennings, Yvonne Blomer and DC Reid, Marita Dachsel and Nancy Lee (eds.) Lisa Ahier, with Susan Musgrave, Stephen Collis (ed.)for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “‘The healing nature of writing’”

Family memories and history can lead in many different directions !