Pop cultural analytics

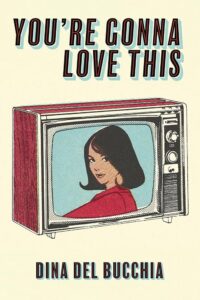

You’re Gonna Love This

by Dina Del Bucchia

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2024

$19.95 / 9781772016123

Jump Scare

by Daniel Zomparelli

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2024

$19.95 / 9781772016109

Reviewed by Carellin Brooks

*

Poets have spun gold out of the meanest dross.

Arleen Paré’s Paper Trail is the paradigmatic example, an examination in verse of the narrator’s despair and boredom as she repeatedly recalculates her projected retirement income, wondering if she’s yet amassed enough to quit, while marooned in a series of incredibly uninteresting meetings.

Vancouver’s Dina Del Bucchia has a similar bent. In the book-length poem You’re Gonna Love This, she makes meaning out of quotidian entertainments: the shows we watch, discuss later, and as the title describes, recommend to our friends as a way to connect.

The subject matter could feel glib, but in Del Bucchia’s capable hands it turns out anything but. Reflecting on a past relationship, the speaker observes:

We were different. Except we both wanted

other people to do as we said,

what we told them to do, but that’s not

what people do. Even if you love them.

In another section, the poet remarks on the absurdity of failed entertainment, linking it to other failures—

…Not that we always

Have to like what we’re watching. We’re trained

to be around people we dislike all the time.

That’s work, every day, go in, make money,

work enough hours to retain benefits.

In this poem, the speaker yearns for an alternative to being around people she dislikes, for money. Best would be a space as clear, as sharp as the worlds inhabited by the protagonists of these stories, with their exaggerated outfits and situations. “It would be a dream to walk around without an umbrella,” she thinks, looking out the window at an uninspiring rainy view, “but a bigger dream would be to live in some kind of alternate reality.”

This is why we watch, Del Bucchia’s poem suggests. TV shows, despite being ordinary, become meaningful because of how they overlap, and don’t, with our lives. The possibility of that meaning ensures our return to the screen over and over, despite the likelihood of disappointment. As the speaker explains, “I just want something that brings/genuine human feeling and also numbs/the parts of me I am not in the mood for.”

(Who doesn’t? There’s a reason I rush home after every workday, whether exhausting or mundane, to watch Selling Sunset, a purported reality show about female Los Angeles realtors wearing tiny outfits and six-inch stilettos. You’re gonna love it!)

Del Bucchia’s speaker’s reality includes not-so-exciting jobs and a chronically ill partner. In defence, she dreams of fun: cocktails, shopping trips, entertainment provided by or for her. She isn’t particular. How does she fit into the narrative? What character will she inhabit today? What outfit will make it all happen, catapult her into the life of excitement she consumes onscreen?

Daniel Zomparelli’s Jump Scare gestures towards many of the same pop-culture tropes as You’re Gonna Love This, but his book is even darker than the half sunny-side-up latter. The two collaborated on a book and podcast and are published by the same press, and their writing also shares a love of online minutiae. But former Vancouver author Zomparelli’s poetry is written specifically to explore additional tough topics like his sister and mother’s death, his anxiety and autism, and the ways in which gay culture has mutated online in response to capitalism, increasing triviality, and surrounding toxic homophobia.

That’s not to say this book isn’t clever, too. Zomparelli makes good use of the review feature in Word, annotating his own found poem, “Frankenstein’s Monster VS. Dracula (VS. Me).” The annotations create a second shadow poem, one that hints at the events surrounding “Frankenstein’s”: “you jumped in a car and drove through the night because she was in the hospital again.” The monster in the official poem, evoked by lines from Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley’s novels, is deliberately juxtaposed with the monstrosity of the relative’s situation. “I must destroy the monster.” So ends “Frankenstein’s,” and so does everyone feel when rendered utterly helpless in the face of a loved one’s disastrous medical news. The futility of that wish–the impossibility of destroying the monster–is the truly terrifying thing, so much more than the vampire or the doctor’s patched-together creation.

The monster becomes a convenient way to visualize cancer in “He Drags Her Body, / or Working Backwards”: “The monster, burned to black ash, was waiting for me inside his cage. / I told you he would get out, but you were certain he was trapped. / When you looked away, he escaped.” The anxious speaker, conjuring dreams or nightmares, is the only one who understands everything that has gone or could go wrong. If only the “you” of the poem could perceive her peril! In vain, the narrator lists medications, procedures, symptoms. It’s already clear: nothing will stop the worst from happening. The dead will visit in dreams, shop for groceries or call on the way to the car crash, oblivious to their fates, but never again be alive.

Each inside cover of Jump Scare is printed with a red balloon, the only colour aside from the cover. “Give me a red balloon // let me float”: so the narrator implores in the titular poem. The red balloon: hope for something beyond, like del Bucchia’s speaker dreams of in You’re Gonna Love This: “Selfishly I pine for entertainment, crave experiences / that might hurt others, for flickers of fun / a surge of joy, serotonin rising.”

But the red balloon doesn’t just symbolize a surge of joy. It is also the lure carried by the bad clown, the pretend toy tempting children to their doom in a horror movie, the balloon string like a thread: “I think so much about the thread / how it connects us, when one of / us pulls away, a tear.” This must be the first time anyone’s ever visualized Freddy Krueger as a gay pin-up, caught unawares.

“He flips around onto his belly, kicks his legs up / puts his finger to his lip, cuts it a little.” Hilarious, and horrific: Zomparelli’s calling card.

It’s to our lasting benefit that we have these two astute chroniclers of pop culture to explore the fun and the monstrosity of our everyday entertainments. Perhaps next time we cue up the latest must see-show we’ll pause to ponder its deeper meaning? Unlikely, but no matter. Zomparelli and Del Bucchia will do the thinking for us.

[Editor’s note: alongside Andrea Warner, Dina Del Bucchia and Daniel Zomparelli will read April 28 during a Triple Treat Book Launch (hosted by Jen Sookfong Lee) in Vancouver that begins at 7:00pm.]

*

Carellin Brooks is the author of the poetry collection Learned (Book*hug, 2022) and four other books. She lives in Vancouver. [Editor’s note: Learned (Book*hug, 2022), a poetry collection about Brooks’ time at Oxford and in the fleshpots of London, was reviewed in BCR by Linda Rogers. Brooks has reviewed Mx. Sly, Debbie Bateman, Michael V. Smith, Buffy Cram and Maryanna Gabriel for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster