‘Relentless human demands’

River Notes: Drought and the Twilight of the American West – A Natural and Human History of the Colorado (Revised Edition)

by Wade Davis

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2023

$22.95 / 9781778401428

Reviewed by Steve Koerner

*

Roman Polanski’s 1974 film Chinatown1 describes a plot involving a sinister cabal of businessmen and land developers who are out to subvert the supply of scarce public water in the Los Angeles area for their own nefarious purposes.

There are no similar instances of the criminality and violence depicted in the Polanski film to be found inside River Notes: Drought and the Twilight of the American West. However, author Wade Davis, amongst other things a UBC professor of Anthropology and former National Geographic Society Explorer-in-Residence, does address the theme of water, its use and misuse and, more particularly in this case, how the Colorado River has been changed, much for the worse, by human activity.

The book was originally published back in 2012 but has now reappeared together with a new introduction prepared by Davis to update the earlier edition.

This isn’t the first time Davis has written about a river, having done so over twenty-five years ago with One River2 which focuses on the Amazon and, more recently, Magdalena3, also set in South America. Davis has a long-time familiarity with the Colorado, dating back to 1967 when he first visited it as a teenager. Even then the Colorado’s path was already interrupted by a series of dams created in order to make the deserts bloom, enabling both population growth and large-scale agriculture.

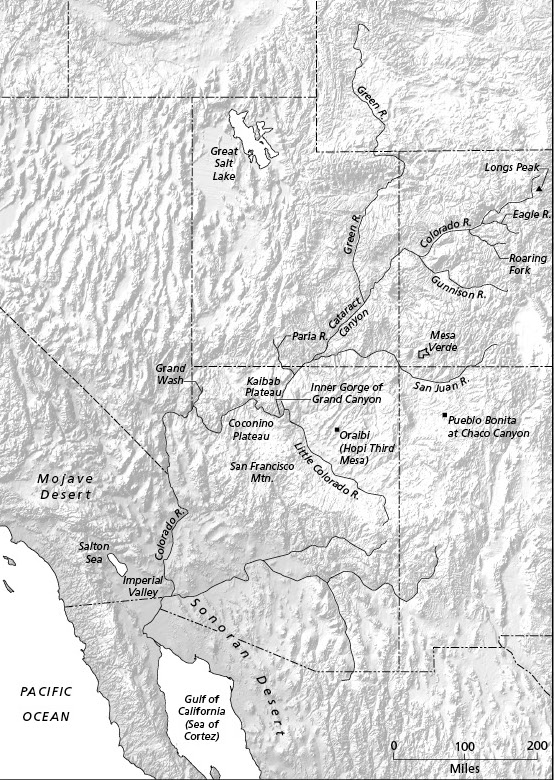

Davis presents a melancholy account of the despoliation of the Colorado, which he calls “The American Nile” and “The River of Life.” Relentless human demands upon it, especially those caused by the dams, have leeched off such vast amounts of water that, by the time the Colorado finally reaches the Gulf of California in Mexico, all that remains is “a shadow upon the sand, its delta dry and deserted, its flow a toxic trickle seeping into the sea.”

That represents only part of the damage caused by these massive water storage and power generation projects. Sites of extraordinary natural beauty, not least Glen Canyon, a spot, in Davis’ words, “so exquisite that its loss would be mourned for generations,” have been submerged by reservoir waters. Even though the dam builders promised that these reservoirs, when completed, would offer a wide range of recreational opportunities, Davis calls them a “featureless sheet of water.”

Yet at first this dam building strategy seemed to have been a spectacular success. The population living within the mostly arid southwestern United States region traversed by the Colorado has dramatically increased. Cities such as Las Vegas, Tucson, Phoenix, and Albuquerque grew in size by two, three-fold and more from the 1940s onwards. Agricultural production, thanks to irrigation projects largely reliant on the Colorado River’s water, reached the point where it is feeding a substantial number of people living in the western US and Canada.

Fortunately, during this era, especially in the 1980s, there was also abundant precipitation, keeping reservoirs like ‘Lakes’ Mead and Powell full or close to it. Starting around 2010 that changed. Rain and snowfall has decreased, leading to a multi-year drought which continues to this day.

All of which has had a major impact on the dam system. Water levels at ‘Lake’ Meade, for example, the gigantic reservoir created by the Hoover dam, have significantly dropped. Macabre sights, such as human remains, often those of the victims of gangland murders in nearby Las Vegas, are now being revealed as they become uncovered by the receding reservoir.

Hence a dilemma now needs to be addressed: water demand in the south-west US now exceeds the total natural flow of the Colorado. In order to make up the difference water has been steadily shunted away from the reservoirs causing their levels to further drop. That in turn has impaired the dams’ power generating capacity.

Agriculture is also under pressure. Certain crops, especially almond trees, are notoriously thirsty. Irrigation not only sustains crops used for human consumption but also fodder, grown in large volumes in order to feed cattle. As Davis observes, “I found it unsettling to learn that the entire water crisis in the American west comes down to cows eating alfalfa in a landscape where neither belongs.”

So, the future of the entire Colorado River area seems bleak, despite periodic bouts of winter rain and snowfall. Can it remain America’s foremost agriculture producer, able to sustain the millions of people that live around the southwest and beyond? If the flow of the Colorado River continues to fall off, where will the water necessary for power and irrigation come from?

Davis concludes that the answers aren’t and won’t be easy to find.

Still, even if he doesn’t mention it anywhere in River Notes, this ongoing water crisis in the American southwest has ominous implications for British Columbia and western Canada in our comparatively near future.

The more immediate concern is food security. If the American drought persists, as seems likely, then how can Canadians, especially here in British Columbia, expect to rely on future imports of the produce from the southwest and California that fills up such a large proportion of our supermarket shelves? Equally worrying will be the pressure that could be put on Canada by some future American government to gain access to our fresh water in order to replenish their diminishing rivers and keep the irrigation canals flowing.

This is not an imaginary or hypothetical threat. Back in the 1960s, the American engineering firm Parsons conducted extensive survey work around British Columbia to investigate the feasibility of diverting Canadian river waters southwards to the US. The diversion concept became known as the North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA) and quickly attracted controversy in both Canada and the USA.

Critics claimed it would result in widespread environmental damage throughout northcentral British Columbia and the southern Yukon Territory. There would be extensive flooding, very possibly leading to the inundation of population centres such as Prince George.

Fortunately, so far Canadian governments have successfully resisted NAWAPA. But for how much longer if the drought and the Colorado River water crisis lingers on? That might well cause more determined political and economic pressure from south of the border to be put on Canada and force acceptance of NAWAPA. If so, this monstrous project would inflict damage to Canadian rivers and our landscape and environment on a scale far beyond anything Davis, or even Polanski and his Hollywood scriptwriters, could possibly describe.

*

Steve Koerner has a BA (Honours) in History from the University of Victoria and a PhD in Social History from Warwick University in the UK. He is the author of The Strange Death of the British Motor Cycle Industry (Lancaster UK: Carnegie Publishing, 2012). Koerner lives in Victoria B.C.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes: