Earhart: poet, go-getter, everywoman

Lady Bird

by Kerry Gilbert

Holstein: Exile Editions, 2023

$19.95 / 9781990773105

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

The book is about flying. You start in a whiteout, with a blank page. Let’s call it heavy cloud. You can’t see through to find a place to land. The plane has to fly on. It had better not run out of fuel.

The original plane was pioneer pilot and early feminist Amelia Earhart’s Elektra. It ran out of fuel on July 2, 1937 and vanished in the middle of the Pacific. People have been telling stories about her bones ever since.

Traditionally, stories have a line, that gets sparked by something, then thrusts on to a rising action, a crisis, and a resolution.

Okanagan poet Kerry Gilbert (Little Red) uses different technology. Her book is carefully folded this way and then that way, lifted up and set down, turned then folded again, and again and, look, you have a plane. You hold it in your hands. It holds you, and its cargo.

I asked Gilbert if a folded airplane was an appropriate image for the book. She said it was. So, I asked if it were appropriate to look at Lady Bird as the story of a girl called Kerry, holding a toy plane and running around, imagining she was flying. “I did that a lot,” she said. Plus: “It’s hard being a woman. There are so many pressures on you. I feel so thin. Stretched out.” As Gilbert writes in lines that embody well the feeling of getting knocked about in turbulence:

flying is so much about balance, and

that’s it, really. that feeling that at

any moment i could fall out of this sky

woman/mother/writer/teacher, particles of

debris and it forces acids from my stomach up.

Lady Bird contains explanations of the balance that is flight, how the plane creates a downward push that lifts it up. In the image above, the process goes along well for four lines and then is reversed. A crash threatens.

It is averted by the writing of this book, which pushes down on… just the air that Earhart vanished into. That’s all. It is enough.

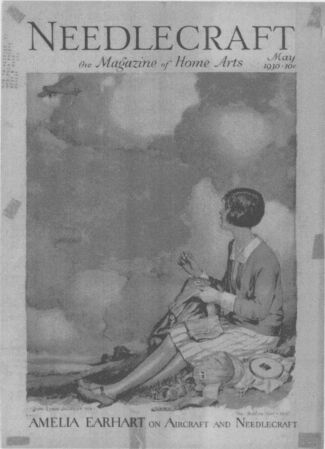

I love the irony of of Gilbert’s curated image to the left: what was (perhaps) presented as a daydream to watch while sewing has in the last 94 years become a map of how far North American women have come.

Earhart’s bones are foundational in Lady Bird. The book documents many stories about them, “all 99% certain that they have solved the mystery,” Gilbert told me. “I don’t believe in any of them,” she also added, “but they keep me grounded.”

That’s quite a statement for a book created from a series of file folders (paper wings, surely), each opening with Earhart’s own long-suppressed poetry, Gilbert’s found poems about early feminist aeronauts (in balloons) and the story of Kerry and Amelia talking to each other late at night.

In the process, Gilbert navigates into life as a woman after the age of forty, the age when Earhart was lost and Gilbert feared she would be too. As she writes,

they say in hollywood women disappear

after fifty—can only play stock roles

to well-aging men

Even her punctuation brings her feminist point home, setting most marks in the centres of sentences, and only at the ends in lines that continue on. The method folds material in.

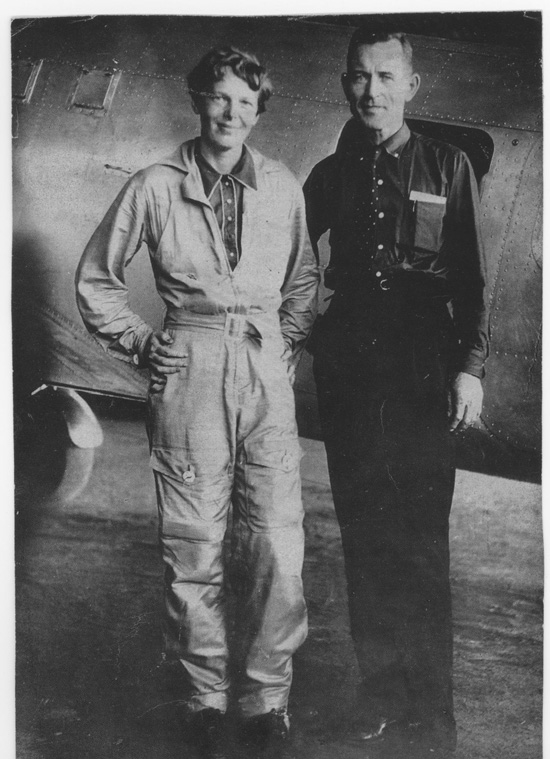

As for turbulence, Earhart had to balance considerable challenges. It wasn’t enough to be an aviator. She had to be an All-American woman, too.

At the time of the supposed crash of Earhart’s plane over the Pacific on July 2, 1937 (she was accompanied by her navigator, Fred Noonan), all the pair had to do was find Howland, a tiny island in the middle of a vast sea, and land on it to refuel. What punctuation! Looking further:

marshall islanders’ legend goes

that fishermen saw the plane go down

and two caucasian fliers emerge

This plane is a woman’s body!

This is uncharted territory. Earhart, searching for Howland Island, suspecting that no one hears her transmissions, whistles into her microphone, hoping that someone will hear. There are no maps for that, just guts.

Gilbert presents a vision that a trade wind turned Earhart’s plane around, that she glided to Papua New Guinea, where children give Earhart garlands of flowers. As this image (equally Gilbert and Earhart now), she then tells young girls stories at night around a fire, about “places / you have been…books / you wrote, about birth control and / the vote. you teach them how to fly.”

Only here at the end of the book does Gilbert gently reveal that the ‘you’ the book addresses is less Gilbert speaking rhetorically to an Earhart who can’t hear than girls, to give them something more feminine than an image of bones.

For sure. The book is not a coffin, after all, but a vehicle built to honour Earhart as a woman instead of the object often confused with one and which could perhaps best be called a media image. It keeps Earhart alive, but bittersweetly only in a new image placed into the imagination. To be clear, this feminist story is not a gendered one. Its structures of inclusion can open just as well within boys.

As Gilbert points out, many pilots never saw planes from a woman’s point of view. Another early female pilot, Helen Richey, for example, “beat out seven male competitors for a position / as co-pilot on central airways,” but quit a year later because “pilots were unhappy about a female / invading the male bastion / of the cockpit,” resulting in a directive forbidding women to fly while menstruating. Those are dismissive images, including that ridiculous cockpit.

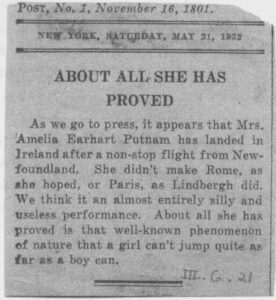

It gets worse. Bones and even aircraft aluminum found near the alleged crash site have been measured, subjected to DNA analysis and bombarded with neutron scans, all to prove that Earhart landed, or crashed, in one place or another, or to prove technique—but never to show her character. Here’s an example of Earhart’s social body instead, unearthed by the archaeologist-poet Kerry Gilbert:

What a non-sequitur.

“What,” I asked Gilbert, “if you were to print the book on sheets of paper, fold them into airplanes, take them up on the mountain above town with your friends, launch them together into the sky and let the wind take them?”

“I’d like that a lot,” she replied.

“The whole ocean is terrible,” she said as well, “it is all these women, all women, millions of women, staring up. They are the sea that Amelia has crashed into.”

Terrible it may be, but it is one of those images that centres the book. In one of her stories about Earhart, Gilbert presents another: balloons rising from the deep sea, each lifting a woman towards the surface. At another time, Gilbert presents Earhart flying on without even a plane around her. We don’t know for how long, but it is an image with more hope than media images of Earhart flying while smiling for the camera at the same time.

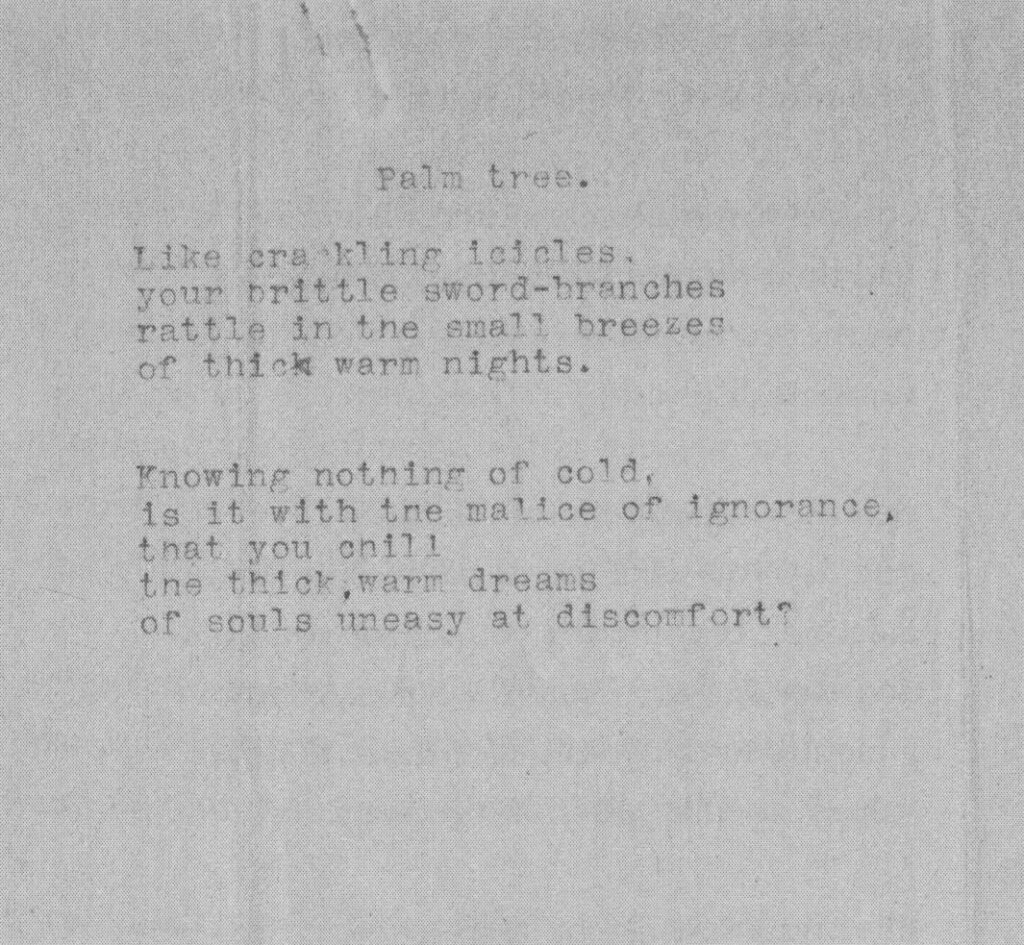

When Earhart relaxes her guard, she is Emil A. Harte, a poet writing on death, love, and mortality, in a kind of double code: first, to gain publishing access more readily granted to men, and second to write in a secret language to her sister, outside of prying eyes. Here’s some from Lady Bird:

Gilbert chose to honour this poetry as individual, displaying character (which it does), but it does have other backgrounds. Socially, it is an example of what the poet Ezra Pound called “Amygism,” a term he used to disparage the poet Amy Lowell, who softened the revolutionary poetics of the First World War period by being plain, direct, and emotional.

Pound created a well-known poetry of compression called “Imagism” in the name of modern mechanization. In it, emotion was buried in technique rather than openly expressed—a dismissal of early twentieth century verse written for and by women. Such modernism had many strengths. Its gendered dismissal was not one.

The counterrevolution lived on for decades before it grew into the tradition that Gilbert is still working at extending. Earhart stands as a pioneer in this group. Ironically, she mastered technology more than Pound ever did, even though her poems could have used a navigator—an editor.

Now she has one. A humble one. Perhaps overly so. Lady Bird’s ballooning threads are intricately worked as narratives of women breaking limitations at the cost of their own lives. The cloth the book is woven into, the one into which Gilbert brings rigour to Earhart’s unflinching expressions of character, is only lightly suggested.

“I have a responsibility of carrying it on and not letting the story go,” Gilbert told me. “I didn’t want her to be the bones.”

Look at that. Earhart is not flying solo now.

*

Harold Rhenisch’s grandmother Charlotte was a doctor while Earhart was flying. During WWII she flew solo: responsible for a regional hospital, 24,000 patients, a Ukrainian maid she rescued from a concentration camp, an escaped French resistance fighter (in the basement), an escaped Russian POW (in the attic) and her own 7 children, half the time as a single mother. She jumped farther than her husband Hans, also a doctor. He crashed. Harold has written thirty-four books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys, including the story of Hans and Charlotte. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as on The Bowron Lakes (2006), all published by Country Lights; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. His The Salmon Shanties: A Cascadian Song Cycle, a series of drum songs for the salmon in English and Chinook Wawa and honouring the poet Charles Lillard, is appearing this fall from Oskana Editions. Harold lives in an old Japanese orchard on unceded Syilx Territory above Canim Bay on Okanagan Lake. [Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has reviewed books by Robert Hilles, Sho Yamagushiku, Bradley Peters, Aaron Tucker, Dale Tracy, Dominique Bernier-Cormier, Selina Boan, Joseph Dandurand, Délani Valin, Robert Bringhurst, Rayya Liebich, Sarah de Leeuw, Roger Farr, Stephan Torre, Don Gayton, and Calvin White for BCR. His book Landings (Burton House, 2021) was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong; The Tree Whisperer (Gaspereau, 2021) was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “Earhart: poet, go-getter, everywoman”

Excellent review, Harold, and very encouraging for women today who long to fly.