‘To go north and missionize’

The Holy Spirit and the Eagle Feather: the Struggle for Indigenous Pentecostalism in Canada

by Aaron A.M. Ross

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023

$39.95 / 9780228017660

Reviewed by Richard Butler

*

John Updike’s first rule for book reviewing is as follows:

Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.

Or in other words, don’t review the book you wished the author had written.

I confess that when I first looked into Aaron Ross’s The Holy Spirit and the Eagle Feather, I had my hopes up. Was this to be another book like Susan Neylan’s The Heavens Are Changing, a marvelous history of nineteenth-century protestant missions and Tsimshian Christianity1, an account of inter-cultural spiritual first contact, exchange and amalgamation, but involving Pentecostal missionizing of northern Indigenous people?

It was not.

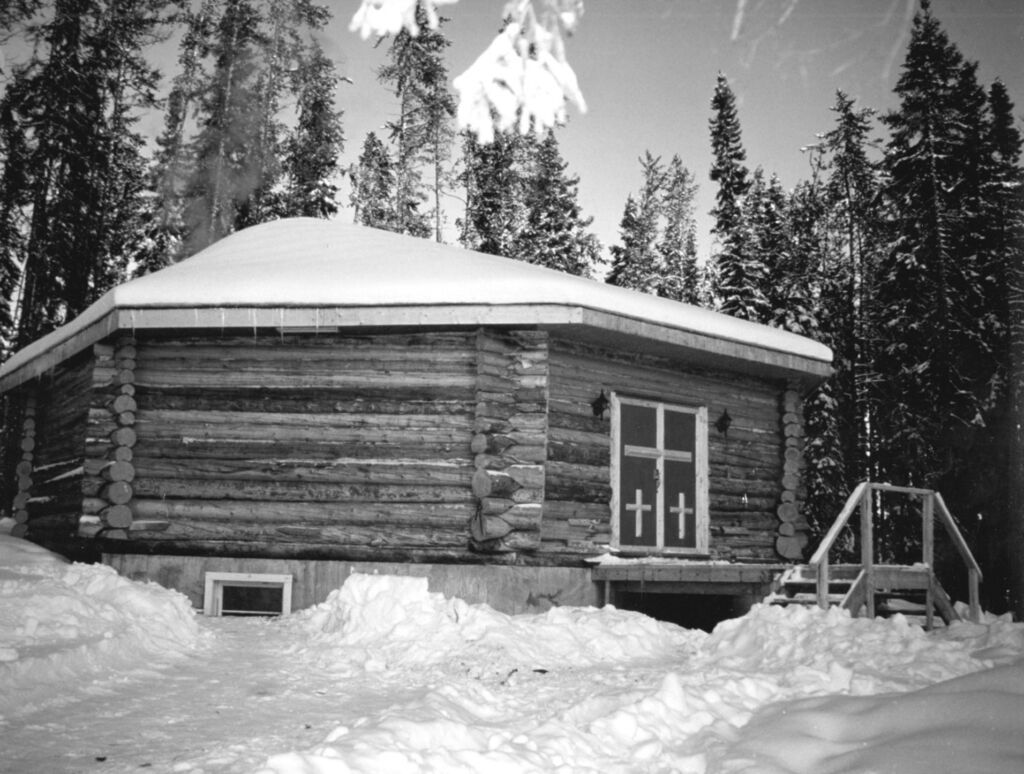

Ross’s book deals instead with a decidedly post-contact series of encounters, beginning in and around the 1950s, when Pentecostal missionary James Spillenaar felt a call to go north and missionize:

Spillenaar’s passion to travel north equaled his passion for evangelism in general. It was as though the more cold, northerly, and remote, the more attractive the destination became for Spillenaar. His desire was not focused on any particular group of people. …. At this time, his was a geographic vocation rather than a demographic one.

Part of the geographic challenge became how to missionize beyond where the roads ended. By the 1940s and ‘50s, Ross tells us, missionary aviation was developing elsewhere in the world. Spillenaar numbered among the vanguard in its development, affording him a broad denominational celebrity: his aircraft was popularly referred to as “the Wings of the Gospel.” It is true that the further north he travelled, the more likely he was to encounter Indigenous people. But that was not the original impetus, as it had been with William Duncan and the founding of Metlakatla, as told in Susan Neylan’s book.

Nor is The Holy Spirit and the Eagle Feather a social history, exploring what must have been the deplorable conditions of northern Indigenous Peoples as the Pentecostal missionaries found them.

The main reason for Ross’s lack of social commentary is likely that, by the 1950s and ‘60s, and even for northern Peoples, the fundamental harm had been done. But there is little sense of what life was like for those folks.

That brings me to a turning point in this review of The Holy Spirit and the Eagle Feather. Ross was not trying to write a book like Susan Neylan’s. He has instead written an institutional history of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada (PAOC) and its mission to the lands around Hudson’s Bay through its subsidiary, the Northland Mission (NLM).

Ross has produced a work of considerable scholarship, involving extensive archival research and almost 100 pages of endnotes and bibliography. It is for the most part very well-written. I have only two quibbles in that regard:

- First, in places, Ross’s book devolves into a bare recitation of which individuals did what and where without giving any sense of who those people were, what setting up a mission involved, or even telling us where in Ontario and elsewhere those places were located or what they were like. At those points, which are fortunately few, the book reads more like a record for posterity than a narrative of the development of Pentecostalism in Canada.

- Second, and this really is a picky point, I do wish Ross hadn’t used the academic and somewhat pretentious word “monograph” where “book” would do.

The Holy Spirit and the Eagle Feather is also a labour of love—and not only because it became, as Ross says, a “constant companion” in the life of the author’s family over the span of a decade.

Ross’s book had its genesis in the 2012 letter of apology, forgiveness and reconciliation issued by the leadership of the PAOC and responded to by its Aboriginal Ministries Guiding Group (successor to the NLM).2 Ross says he found that the 2012 apology and statement

…sent me along a path of intrigue and interest. What is more, I was not the only one unaware of the issues addressed in 2012. Now, over a decade later, it is my hope that these pages shed some light on aspects of that story, as well as its present-day outcomes.

In this present book, Ross has himself embarked on a mission, in the Christian sense. It has been a mission of love in which he engages in re-missionizing his own denomination to a better understanding of its historical relations with the Indigenous people whom the Northland Mission set out to reach. The book he has written addresses most if not all the points of apology by fleshing out what really happened, what was done wrong, and why it was done the way it was.

Therein lies both the importance of this book and Aaron Ross’s courage in writing it.

Courage because what we have here is a British Columbia pastor speaking truth to the power of institutional memory about the Northland Mission in central Canada. The need to establish objective distance thus accounts for all the scholarly apparatus. Ross needs his book to be seen as a monograph.

Importance because, in principle, when we apologize, we should really know—and fully engage with—what it is we are apologizing for.

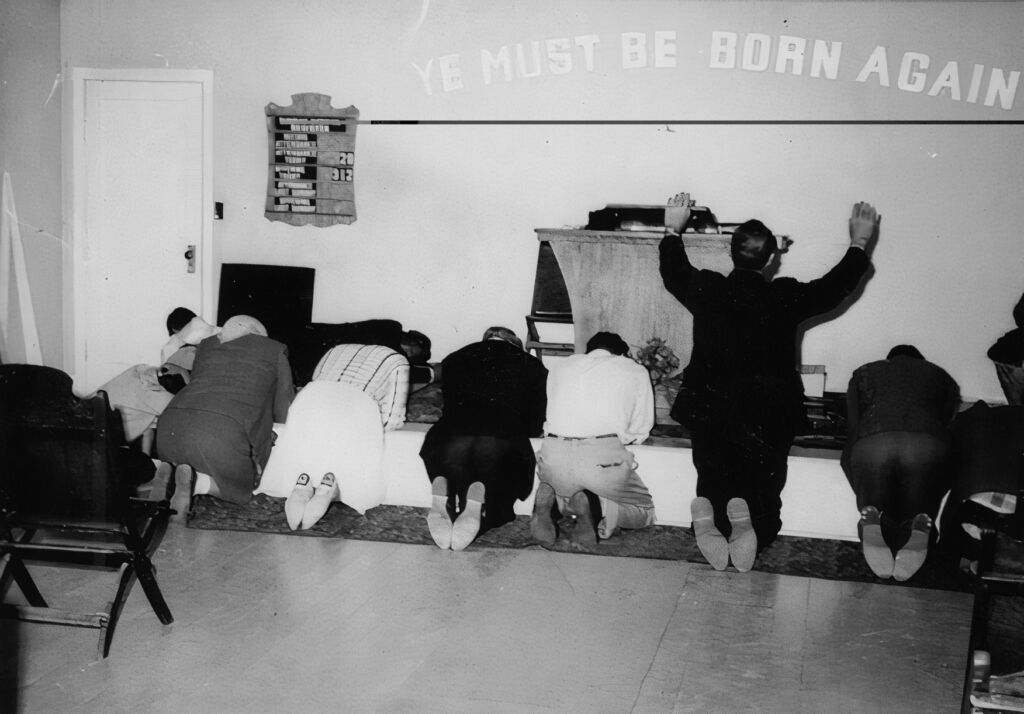

In his introduction, Ross sets out the core issue for us. One of the most important features of the Northland Mission was that the first wave of Indigenous adherents was to be trained to replace Euro-Canadian itinerant missionaries and create a self-perpetuating Indigenous church. Indigenous culture was to be viewed as equally valid. This was the so-called “indigenous principle.” Yet

[t]hroughout most of the NLM’s existence, its Euro-Canadian leadership claimed to support the indigenous principle but subtly undermined it, doubting and ignoring Indigenous ministers and opposing the integration of Indigenous culture with Pentecostalism. ….In the Pentecostal missionary historical record, the indigenous principle readily morphs into inculturation. Rather than accepting Indigenous culture as equally valid to Euro-Canadian culture, PAOC missionaries often opposed Indigenous culture and advocated their own, demonstrating colonial and paternalistic behaviors.

Ross’s book strives to “uncover assumptions, biases and sentiments behind various parties’ motivations,” including from both what was said and what was left unsaid.

In Chapter 1, Ross describes, among other things, Pentecostalism and its origins. He also gives a brief summary of Christian missionizing in what is now Canada. Both are needed as context.

One of the most interesting aspects of this chapter is Ross’s succinct and powerful description of the shortcomings of what he terms the longer-established churches in their historical dealings with Indigenous people. He speaks of a joint socioeconomic and spiritual colonizing on the part of the government and those churches, toward the mutual objective of assimilation.

The Pentecostalists—themselves on the margins of established Christianity in Canada—are implied to have lacked as much of an assimilating objective. Ross says that “while the PAOC may not have been innocent of attempting to assimilate Indigenous mission participants, it did have an advantage [of] not represent[ing] as much of the pre-existing cultural assimilative history….” Maybe so, but we must wait until later in the book to engage the idea that conversion itself is a possible instance of spiritual assimilation.

Ross suggests it was Indigenous peoples’ dissatisfaction with the shortcomings of Christianity as offered by the longer-established churches that made those people so attracted to the new, simple form offer by Pentecostalists. As proof, Ross reports, they converted in droves. One of the troubling features about this book for a non-Pentecostal like myself is the denomination’s unabashed objective of trying to convert as many people as possible.

During Chapter 2, Ross is pretty gentle in his criticisms. Or perhaps circumspect is a better word, for that chapter deals with the Spillenaar era: the “Heavens Become a Highway.” Aviation allowed greater missionary reach but at the same time diminished missionary depth of engagement. Here today and gone tomorrow. Spillenaar’s personal brand of missionizing was well suited to that approach, but there were inherent problems in terms of continuity. Jim Spillenaar was not going to be the hero of this institutional history.

In Chapter 3, Ross goes on to describe the development of a series of Bible colleges for Indigenous people drawn to missionizing (the NLMBC). These had only mixed success. There are reports of inspired students made ready to go forth; but also reports of lack of funding, resulting in poor standards in accommodation and food, requiring support by student labour. Now where have we heard that before? Yet the NLM Bible College initiative started in the 1950s and ‘60s, just as government and the longer-established churches were starting the long process of winding up the residential school system.

A college was first established in one remote place, then moved to another and then to another. Students were discouraged by the difficulty of obtaining sufficient accreditation to qualify for paid missionary positions, most of which, by default, went to better accredited Euro-Canadians. Ross’s thoughtful summary runs as follows:

The NLMBC, and potentially the PAOC’s understanding of the indigenous principle altogether, was more about pragmatism than about indigenization. ….[U]ltimately the NLMBC became known as a Euro-Canadian acculturating institution…. If indeed the NLMBC’s goal was to meet [Indigenous peoples’] needs, then a resulting administrative and moral obligation would have been the provision of accessible, affordable, effective, practical, and applicable ministerial education….

In Chapter 4, Ross’s critique really hit its stride. That chapter goes to the heart of the matter—what properly constitutes the indigenous principle.

Ross says the NLM records show that “its Euro-Canadian leadership claimed to support the indigenous principle, yet subtly undermined it by not fully trusting Indigenous minister.” What is most interesting, is that the lack of trust was not only pragmatic or financial but also doctrinal. Ross describes it thus:

[C]ontextualization [is a] process of framing the gospel message culturally … so that it makes sense to people on the ground where they live every day…. Rather than accommodate by contextualizing the message, Euro-Canadian leadership instead opposed Indigenous cultural norms, the integration of which they believed could result in something they called syncretism (the fusion of religious markers)….

Chapter 4 describes first the nuances and then the instances and evolution of this conflict from Spillenaar forward. It makes fascinating reading—for me, the most compelling part of the whole book.

Most telling are the following two quotations.

The first comes from Dale Cummins, director of PAOC from 1976 to 1981. Ross reports that the start of Cummins’s directorship showed promise for the indigenous principle, but later turned against it. Contrary to the premise that “Native Christians give authority to biblical witness because … there is something that ‘finds them’ where they live their lives,” Cummins interpreted Indigenous Pentecostal’s spiritual instruction as incorrect and he became troubled by the teachers’ inability to speak English. In that attitude, Ross says, Cummins missed a precious opportunity to advance the indigenous principle.

Here, in a 1979 letter to NLM supporters, is the quotation which best captures the problem:

Perhaps, like me, you hadn’t realized how traditional spirits completely permeated all of life for them. Although outwardly broken, the ancient system still exerts amazing strength. …. Old ideals and beliefs have often been adapted and adopted, even within the Christian church [and] unless we replace [them] with the ideals, goals and purpose of true Christianity, and we demonstrate the Holy Spirit as a beautiful and effective inner control, we leave our Indian brethren in dire circumstances.

The second quotation comes from Rodger Cree, an Indigenous person recruited by Spillenaar. Ross tells of Cree’s background and work. He reports that Cree maintained that “being Indigenous and being Pentecostal were not mutually exclusive. From Cree’s perspective, Indigenous culture was not solely the domain of Indigenous traditional spiritualities.” Embedded in Cree’s attitude is the basic notion that culture does not remain static. That notion is both undeniable correct and vital in considering all aspects of Canada’s so-called “Indian problem” down through the years.

Here is the quotation:

Spreading the Pentecostal message throughout the Indian communities is our highest priority. It not only provides power to save souls, but it is also the power of deliverance for our people from alcoholism, drug abuse, suicide, broken homes, child abuse, teenage pregnancy and a myriad of problems that plague Indian tribes and communities … We believe that the Pentecostal message has the power to set our people free. Further, we believe it is only through an outpouring of the Holy Spirit that there will be real healing throughout our reservations and communities.

That remarkable statement was published in a letter from 1987, decades before the current focus on residential schools and the media coinage of compendious Indigenous “intergenerational trauma.” As noted above, I am not a Pentecostal and elsewhere I have written of my deep antipathy toward organized religion generally; but the idea of the Holy Spirit working in that way person by person and community by community seems to have real hope for beneficial change for Indigenous people and for Canada.

In chapter 5, Ross’s coverage of the story of the NLM continues through to its dissolution and rebirth as the Aboriginal Pentecostal Ministries—which has had increasingly Indigenous leadership. The title of this chapter, “Standing at the Shoreline,” reflects that Indigenous people are still waiting for the full fruition of the indigenous principle in Canadian Pentecostalism. This chapter covers a more compressed time period and is imbued with institutional politics. Accordingly, the narrative is more scattered and sometimes a little difficult to follow.

In the final chapter of The Holy Spirit and the Eagle Feather, Ross returns to the matter of apologies, and to the coming to pass of the 2012 PAOC apology and Aboriginal Pentecostal Ministries’ response. He also provides some reflections on the Pentecostal Assemblies’road forward to reconciliation. In keeping with Updike’s fourth rule of book reviewing, I will not give away the ending but leave it for interested readers to consider for themselves.

But who, then, is the intended audience of Ross’s remarkable monograph? It is not, I think, for general readers: not the easiest book to get through. On the other hand, it emphatically is a book for the present institutional leadership of the PAOC to examine closely and objectively—precisely because it is not easy to get through.

Finally, and perhaps most important, it is a book to give hope to Indigenous Pentecostals, present and future, that Ross has cared enough about them and their call to faith to give the errors of the past and possible pathway to the future the attention they deserve.

- Neylan, The Heavens are Changing 2003 McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal and Kingston, London, Ithaca NY ↩︎

- Space does not allow me to set it out in full, but it is worth following the link to have a look: https://paoc.org/docs/default-source/paoc-family/letter-of-apology-between-the-paoc-and-its-aboriginal-leadership-final-gc2012.pdf?sfvrsn=9073f56a_0 ↩︎

*

Richard Butler is a latter-day settler living on the traditional territory of the lekwungen-speaking Peoples, a retired lawyer and sometime law professor, and more recently a writer on various Indigenous subjects. He is the author of Taking Reconciliation Personally and I Dare Say… Conversations with Indigeneity, published through A & R Publishing.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “‘To go north and missionize’”