‘To the possibilities and pitfalls’

Leaning Out of Windows: An Art and Physics Collaboration

edited by Randy Lee Cutler and Ingrid Koenig

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2023

$45 / 9781773272177

Reviewed by John O’Brian

*

What can art do for science, and what can science do for art? Do shared values exist between the two fields? Is the use of metaphor in the former, for example, comparable to the use of it in the latter? To address these questions, Randy Lee Cutler and Ingrid Koenig, two respected professors at Emily Carr University, received a major research grant to work with scientists at TRIUMF, Canada’s principal centre for particle physics research. Emily Carr is British Columbia’s primary institution for teaching art and design; TRIUMF, located at the University of British Columbia, focuses on searching for the smallest particles in the universe and then developing new technologies from the discoveries.

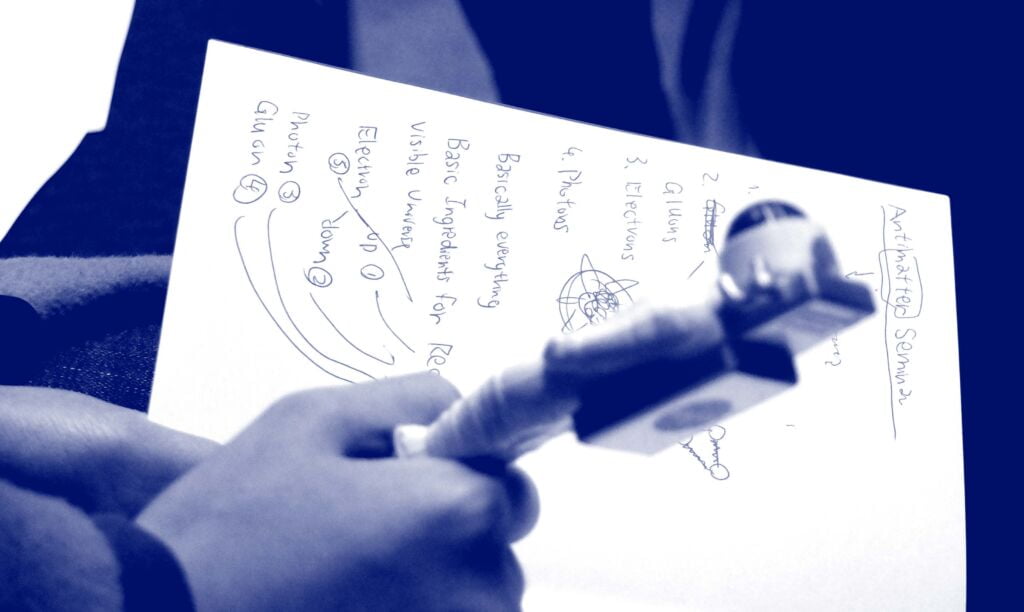

The book Leaning Out of Windows – a publication that is as fascinating as it is ambitious – is the result of a collaboration between Vancouver physicists, artists, and scholars that began in 2016 and extended over six years. Cutler and Koenig initiated the project with senior staff at TRIUMF, and then enlisted artists interested in science who were willing to engage with physicists and scholars. They were grouped into streams, teams, and pairings. The venture involved field trips, seminars, lectures, panel discussions, art exhibitions, numerous meetings, and much else besides. I participated as a panelist on antimatter, with only a vague notion of what the term meant. (I discovered that antimatter is the same as regular matter, except that the particles comprising it have the opposite charge.) As an art historian, I was asked to think about parallel symmetries in the aesthetic realm.

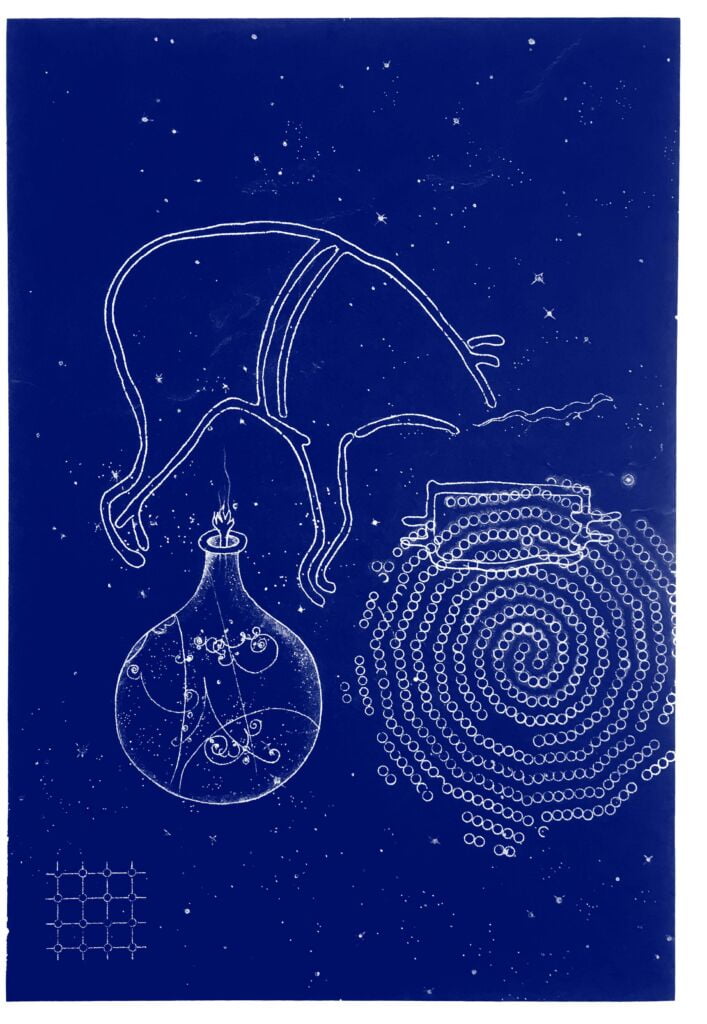

One of the artists selected to participate in the collaboration was Scott Massey, who has worked throughout his career to imagine, as he puts it, the “in-between-ness” of matter in visual terms. “The explanation of physics principles always inspires visualization,” he states in a passage in the book, “and the actual apparatus of physics experimentation look to me like artworks.” One of his works, Beacon, a structure made of birch ply, custom electronics, and a subwoofer driver that is illustrated in the volume, was developed in collaboration with physicists and then displayed in an exhibition at Emily Carr. It is an elegantly compelling work constructed in layers. It would not look out of place – this is meant as a high compliment – as an instrument on the shop floor at TRIUMF.

The title of the book is taken from the German, aus dem Fenster lehnen, a phrase that refers to the possibilities and pitfalls of undertaking interdisciplinary research. In the collaboration, Cutler and Koenig did not ask scientists to make art, nor did they ask artists to become scientists. Instead, they asked what might be gained (or lost) from engaging in such an unlikely collaboration. In particular, they wanted to know if working across the different languages employed by artists and scientists might generate new insights in both fields. In a stroke of genius, Cutler and Koenig invited the physicists to come up with the topics for discussion. I cannot imagine how the collaboration could have proceeded otherwise. It takes a physicist to appreciate the pivotal role that visualization plays in scientific inquiry.

collaboration with TRIUMF physicist Brian Kootte

Djuna Croon, who specializes in dark matter, argues in the book that physicists need to make better use of visualization to convey their ideas persuasively. “We’re still stuck in this very rigid way of representing information,” she states. “And in that sense, we could learn from artists.” As a theoretical physicist, she recognizes the difficulty of trying to analyze and explain what cannot be seen. She also recognizes that artists, who deal constantly with issues of representation and abstraction, are uniquely placed to assist with the problem. Neils Bohr, the Danish physicist who developed the first model of the atom in the early twentieth century, was of a similar mind to Croon. To understand the behaviour of electrons without resorting to mathematical equations, he said, metaphor is required. Poetics, and by extension art, are needed to visualize what is otherwise abstract and inaccessible.

The book contains texts by more than a dozen contributors. Cutler and Koenig set an exacting tone with several cogent essays of introduction and explication; Sanen Güvenç examines riddles and contradictions that gather around the words “emergence” and “void”; Jeff Derksen investigates the intersection of ideas used to explain capitalism by Marx and Engels, such as “creative destruction,” and those of science, such as matter and antimatter particles that annihilate one another when they come into contact; Sadira Rodrigues writes about “a boring berm of dirt” at TRIUMF, where she found that plant life flourishes in irradiated soil; and Mimi Gellman, an artist and scholar with an Ojibwe/Métis worldview, addresses resonances she finds between indigenous knowledge, art, and science. Gellman quotes the Potowatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer on mushrooms: “The makers of this word [mushrooms] understood a world of being, full of unseen energies that animate everything.” The universe and everything in it – art, science, botany – are engaged in the same marvelous dance.

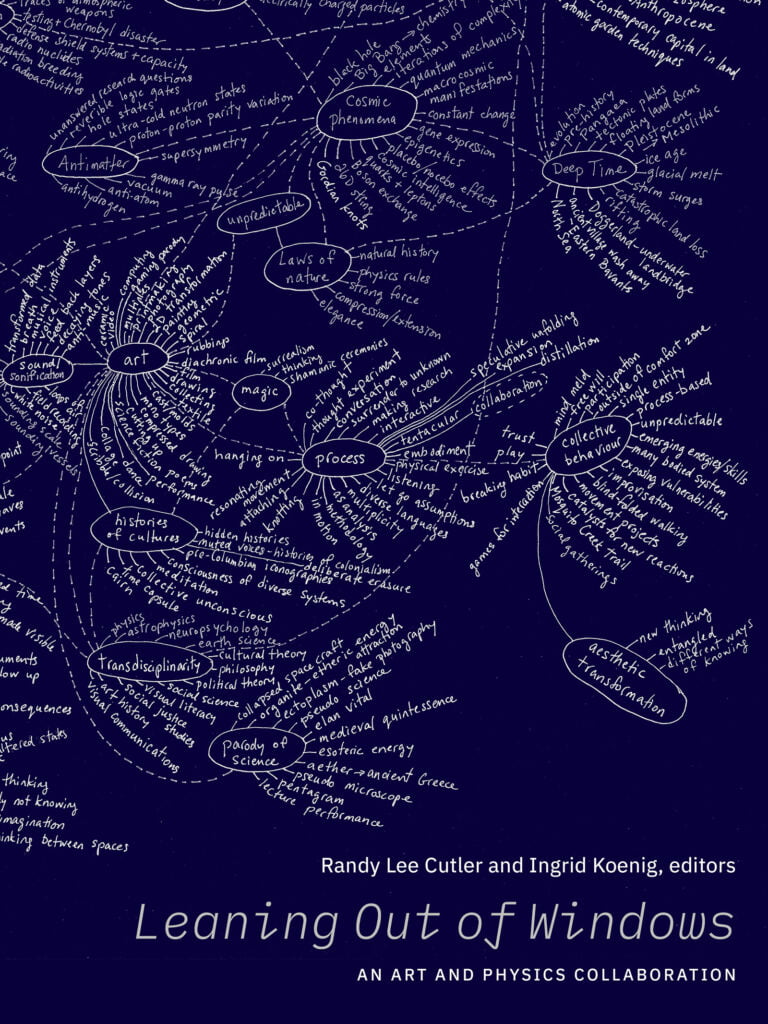

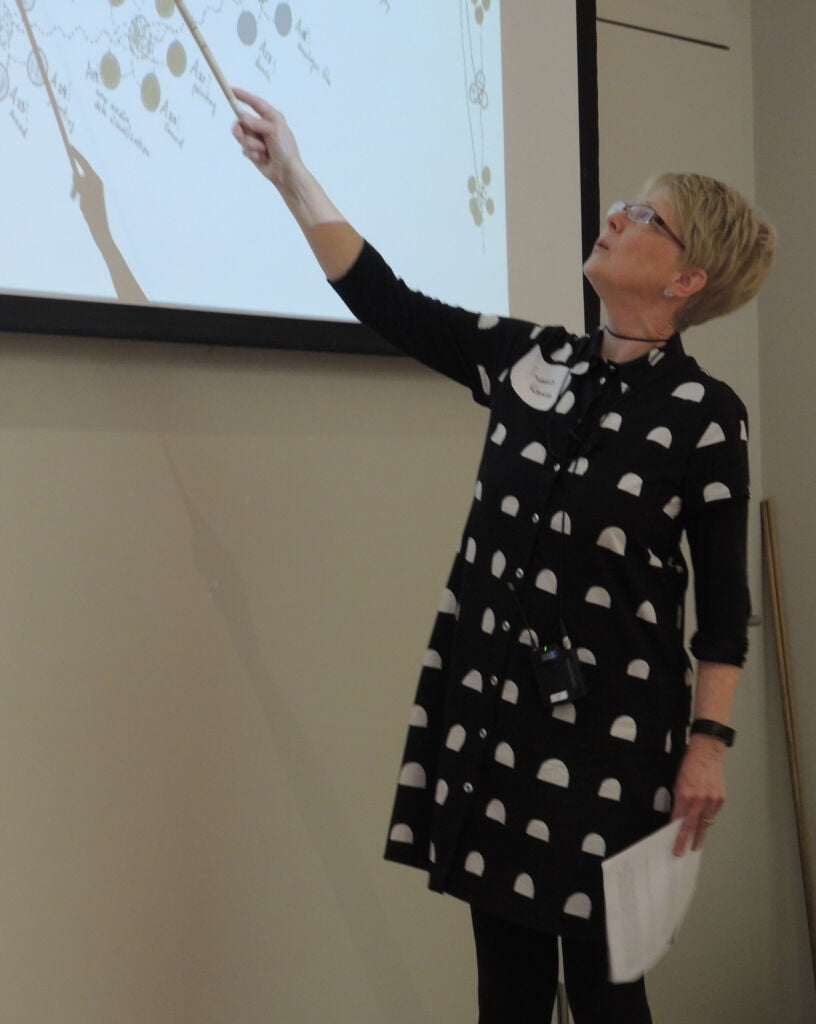

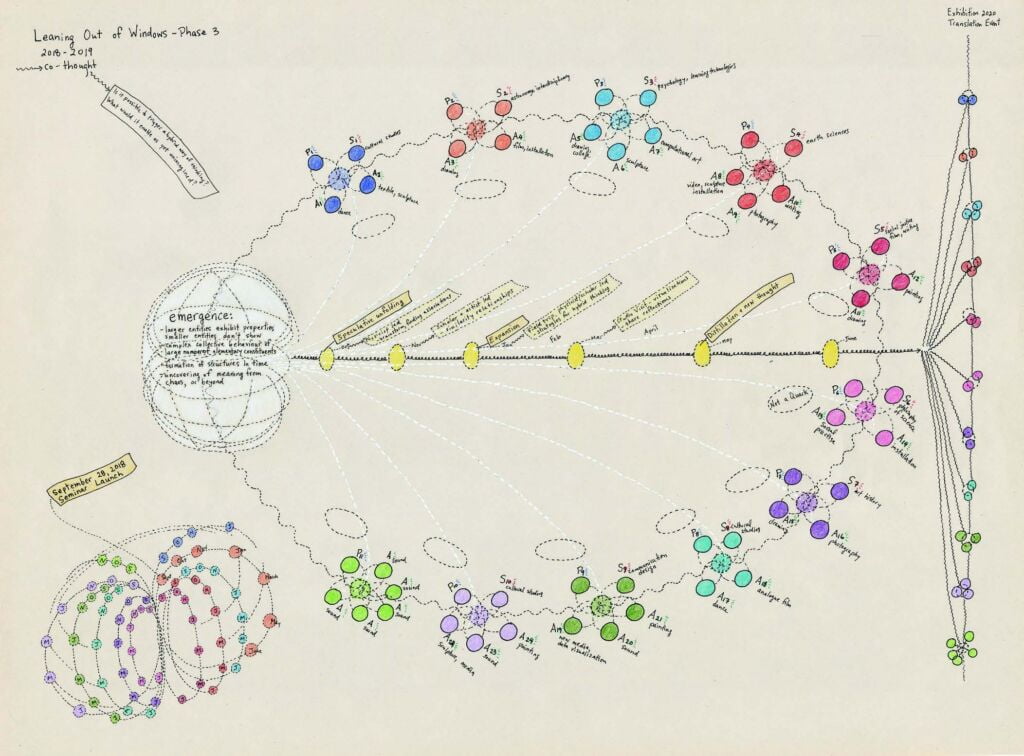

Leaning Out of Windows is beautifully illustrated with works of art, charts, and diagrams. Every artist participating in the collaboration is represented by at least one work, but what really holds the book together are Koenig’s extraordinary hand-produced diagrams that run throughout. They are mesmerizing, a sequence of coloured charts that map the whole enterprise. Initially used as a tool to chart the activities of the collaboration, they seem to have morphed into conceptual artworks over the course of the project. I have spent hours pouring over them, marvelling at their attention to detail and visual sophistication. They belong on the same wall as Joseph Beuys’ blackboard drawings on direct democracy from the 1970s and Mark Lombardi’s conspiratorial diagrams on global finance from the 1990s. Like sociograms used in social network analysis, Koenig started with facts – she must have used thousands of post-it notes to construct her diagrams – and then transcended them. The complex paths of exchange that she traces between physicists, artists, and scholars are a remarkable visual legacy of Leaning Out of Windows.

*

John O’Brian’s latest books are The Bomb in the Wilderness: Photography and the Nuclear Era in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2020) and, co-edited with Claudette Lauzon, Through Post-Atomic Eyes (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020). His next two books, Delirium and John Scott: Firestorm, are in press.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster