On the ragged edge

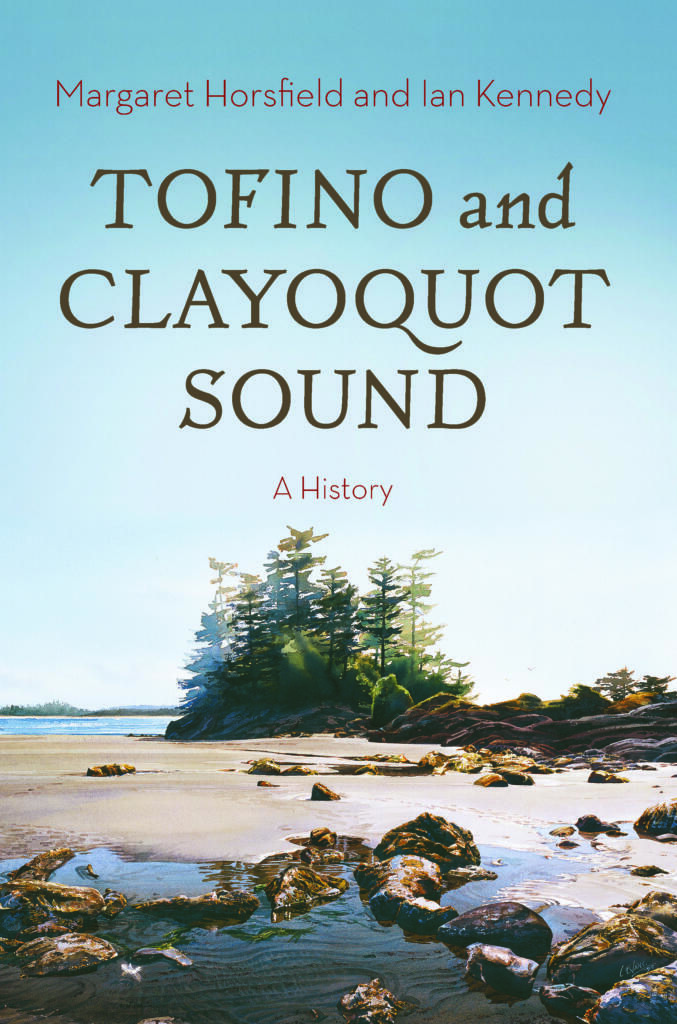

Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History

by Margaret Horsfield and Ian Kennedy

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2023

$34.95 / 9781990776601

Reviewed by Robin Fisher

*

This is a history of life on the fringe. About a place on the ragged edge of the British Columbia coast. An edgy place. If British Columbia is the edge of Canada, then Tofino and its surrounding waters and islands are the outer limits. Most of the themes that make up the mix of British Columbia history played out in Tofino with, at least for recent arrivals, the added ingredient of distance and isolation. For the Nuu-Chah-nulth people this place remained what it has always been: their home.

That is where the authors start the human history of Clayoquot Sound: with thousands of years of First Nations life on this border between sea and land. New arrivals began in the late eighteenth century with the maritime fur trade. It was not a good start. The authors emphasise the violence rather than the reciprocity of the fur trade. The destruction of the trading vessel Tonquin and the people killed on both sides of the encounter brought an end to the fur trade in Clayoquot Sound. There was a lull in outside contact through the first half of the nineteenth century before the storms that followed.

From then on newcomers arrived in waves, borne in by the Pacific that was the highway before a road was built. They came to exploit the resources of the Sound and, in time, some became settlers. The resources of the sea (fishing, whaling, sealing) and the land (lumbering, gold mining, farming) were all the object of hopes and dreams from afar that then encountered the local reality. As people came and endured, trading posts and shops and other services sprang up. Tofino grew slowly while other settlements flourished for a time and then, like Clayoquot on Stubbs Island, faded away.

Renewed newcomer interest in the area began as the fur trade had ended: with a violent encounter. Royal Navy vessels shelled several Ahousaht villages in 1864. The villages were destroyed and people killed because it was said that some Ahousats had murdered the crew of a trading boat. For the next one hundred years colonists took over the area with, as was typical in British Columbia, little regard for First Nations interests and ownership. The treatment of Indigenous people over land and resources was as high handed here as anywhere in the province. Some newcomers, rather than building their own dwelling, actually took up residence in First Nations houses vacated by the seasonal round. Apparently, it was okay for newcomers to have a second seasonal home in the Tofino area but not the original owners. Missionaries came and set up their residential schools to wean children away from the culture of their ancestors. The impact of colonisation on the Nuu-chah-nulth of Clayoquot Sound was not attenuated by distance and isolation.

Those who came and stayed in Tofino and area were not immune from outside interests either and they were often ambivalent about them. The sea was the main route in and out until the mid-twentieth century. The first big change was the establishment of an RCAF air base during the Second World War. Tofino was open to the world in completely new way. The Japanese shelling of Estevan Point brought a distant war close to home and in more ways than one. The Japanese citizens who were kicked out during the Second World War were told in no uncertain terms that they would not welcome back when the war was over.

Tofino interests had been pushing for a road from Port Alberni to the coast for years by the time it was finally opened in 1959. It was rough and ready, but it was the road that really connected Tofino to the outside. Few travellers who faced long delays on Highway 4 last summer would have realised that they were reliving history. The road was built by a partnership between the Provincial Government and forestry companies and initially logging took precedence over tourism. For the first five years the road was closed to all but logging trucks during the day. Day or night, when it first opened, the road was a hairy driving experience. The local doctor noticed an increase in the demand for tranquilizers. If the residents were scared of the road itself, many were also worried about the impact that it would have on their community: and well they might. The road would change Tofino from a small coastal resource village into one of Canada’s tourist meccas. Just like the first visitors, the maritime fur traders, tourists came and saw and left. Along with thousands of tourists there were other newcomers, first the hippy tribe came to drop out, and then the surfers to ride the waves. Old residents felt that Tofino was becoming a town of strangers. New arrivals brought new thinking, particularly about how to care for the environment. Clayoquot Sound became a battle ground between clear cutters and those who wanted to preserve the forests. The First Nations of the area and the more recent arrivals sometimes had similar views on environmental and resource management. It had taken a century of living in the same place for the newcomers to recognize that First Nations people, who had been there for thousands of years, might know something about the stewardship of the environment.

This history of Tofino and Clayoquot Sound is a republication of the 2014 hardcover edition and it is great to have it in this format. The authors have done a tremendous amount of research and written a really detailed history of the area. That is all good and for many readers it will be enough.

There are two things that could have been added. The academic historian in me regrets that there are no footnotes. I know that most will not care too much about that and the authors do often provide detailed citations in the text, but referencing a quote to The British Colonist does not make it easy for other researchers to follow up. More substantively, I think that the authors could have written more about what all the detail adds up too. What are the overarching themes in the history of Tofino and Clayoquot Sound? The impact of colonization on the Nuu-chah-nulth is made plain enough. Newcomers also keenly felt the influence of outside interests. Did it cross the minds of First Nations people that it was poetic justice when new owners were forced the leave their homes when the Pacific Rim National Park was established by the Federal Government? The interplay between insiders and outsiders is a constant theme. There is also a sense that, for many, this part of the coast was a boulevard of broken dreams: “On the borderline/Of the edge” as the song goes. “The Hopeful Coast” (p.205) often did not meet expectations. To survive here people had to expect, and cope with, change. As the authors put it in their last sentence: “Here on the west coast, another wave is always about to break.”

I learned a lot from this book and what more could be said of it? For to learn its history is to appreciate a place more fully. So, next time I visit Tofino, I will look at it with fresh, more informed, eyes. When I stand to admire the big Eik landing cedar, with its iron collar and struts to hold it up, I will know that it was saved from being cut down by protesters who lodged themselves in its high branches for twenty-eight days. Environmental activists also tried, but failed, to stop the adjacent condo development. I will stay there again, but with the understanding that the place has other costs besides a few days rent. Standing on a deck at Eik Landing you can look across Clayoquot Sound with its mix of natural environment and commercial activity, from Tofino to Opitsaht, and watch the boats running back and forth connecting those two different communities.

*

Robin Fisher taught and wrote history as a faculty member at Simon Fraser University before he moved into university administration and contributed to the establishment of two new universities: the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George and Mount Royal University in Calgary. His books include Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (UBC Press, 1977; second edition, 1992) and Duff Pattullo of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 1991). He was the 2022 Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing for Wilson Duff: Coming Back, A Life. Editor’s note: Robin Fisher has reviewed books by Gordon Miller, Art Downs, Richard Boyer, William Frame & Laura Walker, Michael Layland, and Peter Cook, Neil Vallance, John Lutz, Graham Brazier, & Hamar Foster for The British Columbia Review, and contributed two popular essays, The Way We Were: Two Friends, Two Historians and “The Noise of Time” and the Removal of History?

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “On the ragged edge”