Memories of ‘gentle not-quite-back-to-the-landers’

Commune

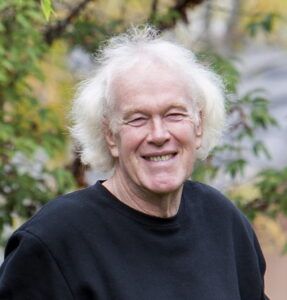

by Des Kennedy

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2023

$24.95 / 9781990776519

Reviewed by Amy Whitmore

*

Commune is an energetic, engaging swing through the ideological and physical dilemmas faced by a group of young adults who shared a farmhouse and land—called Figurative Farm—on Conception Island on the southern coast of British Columbia.

The story is told through segments of memoir written by the last of the farm’s participants, now in his late seventies, at the behest of a young woman searching for meaning in her new life on the same island. Shorter, whose memoir it is, shows segments to Rosalie every Friday. In turn, she gives him her moral take on them.

Shorter and his warrior-woman girlfriend Jess first visit the island on a spur of the moment whim, planning only to stay the afternoon. “In memory, at least,” he recalls, “it was a brilliant morning of sunshine and rainbows and glittering water.” Their ride? A “classic old VW microbus … painted … in wildly psychedelic patterns.”

Then living in Vancouver, Shorter is writing his Master’s thesis in English; Jess works in an outdoor clothing shop. Neither have plans to be back-to-the-landers, despite eschewing the capitalist-consumer society.

Their outlooks change when they visit the island, fall in love with its beauty, and return to look at properties. They find a big old farmhouse with a large pond, old tree stand, some hens, goats, and dogs. Plus, an old-timer willing to sell to the right folks, people who will respect the trees, the land, and his dogs.

With no strings attached, Jess’ wealthy father provides the purchase money. Jess remains close to her father despite rejecting the ways and means by which her father’s money is made.

Six young adults are the initial and most enduring inhabitants of the “commune,” which in fact feels more like a family farm. In the late 1960s they are the first back-to-the-landers on this very rural island. There are some tensions amongst them before they even arrive on the farm, but somehow everyone manages to pull together, for a few years anyway.

In the meantime, wanderers come and go and play walk-on parts in the story.

Shorter’s memoir focuses on moments in the farm’s history, such as the first time the back-to-the-landers came up against the conservative islanders who were determined to stop their nude swimming at a secluded beach.

There are episodes of logging protest against clear cut logging; of aiming to preserve the islands in a nature trust; trying to stop developers who in fact merely want to flip the land. The memoir is fair in presenting the immediate cost to the community when it struggles to implement sustainable logging and preservation practices.

Interspersed within these bigger dilemmas are big moments on the farm itself: do they breed the goats, and if so, what do they do with offspring? How do they constructively get through the oppressive months of damp and rain? Should they go into pig farming, or even get a pig? Should they be a vegan farm?

Kennedy (Heart & Soil) composes knowledgeable and picturesque images of nature:

By late summer, clusters of blackberries hung thick and richly purple. …we’d see some industrious islander gathering buckets of berries destined for jam-making or the wine cellar. In autumn the hedgerow leaves splashed a fine line of colour against the dull, cut hayfields beyond. And after the first frosts, bright red rosehips glistened beside clusters of white snowberry….

The other strength in the Denman Island author’s writing is the development of Shorter’s character in particular. This is rare when writing in first person, where narrators often feel distant, one-dimensional or mere spectators. Which begs the question: why is Rosalie even part of the novel? We learn very little about her other than that she was a cellphone addict who, in a grand gesture, threw her cellphone into Vancouver’s Lost Lagoon and left her PR job for life on the island.

Soon bored, she feels that finding old-timers to write about the back-to-the-land movement on the island will make her feel more engaged with island life. After several false starts, she locates Shorter and talks him into writing the farm’s memoir. He is far more articulate than she anticipates; and before the work is finished she decides it has to be published in a big way, which is not Shorter’s intention.

In the meantime Rosalie makes demeaning, even angry, comments on the content, but not the quality, of his writing. They’re disruptive and obnoxious to the reader. These petty criticisms—“I don’t much care for the centrality of dogs in your narrative”; “Oh, I find this continual head-butting with the Waddington Foundation really rather distasteful”—are rooted in her personal beliefs and experiences, which we never learn, but are intense enough to make Shorter question whether or not he should tailor his content to her beliefs.

Fortunately, he knows doing so would not produce the truest memoir he can write.

Still, Shorter likes how Rosalie livens up his existence and challenges him, and by the end of the book Rosalie has talked Shorter into letting out an empty house on the property and has moved into the farmhouse herself.

Commune is the story of gentle not-quite-back-to-the-landers who farm. Some of them farm. Some of them talk. It is an elegy to the beauty of nature and the effect of that beauty on humans. For some humans, at least.

When reviewing books I read them at least twice, and while this one kept my attention during the first read, it did not upon re-reading.

What is missing from the book is the nitty-gritty decisions made by back-to-the-landers. To use electricity or kerosene? Or some other alternative energy? To wash laundry by hand with a tub and washboard or take laundry to the laundromat? To mow the fields with likely gas-guzzling old harvesters or use scythes? To do most of the work themselves or have work bees? What did this commune do with the fecal waste their composting toilet generated? The urine we know provided nitrogen for their prodigious garden, but where did the fecal waste go?

When Figurative’s farmers realized they couldn’t afford to replace the septic tank, and installed a composting toilet, did they also consider setting up a solar shower outdoors to ease the amount of water still going into the old system? What happened when that system was again overloaded?

Did Enzo’s pot crop really generate enough annual income on that little island where others also grew pot to keep them afloat when the sale of their eggs and vegetables did not generate sufficient cash? Shorter does mention at the end of the book that he became a substitute teacher, just as many back-to-the- landers discovered they needed some kind of work off the farm to finance their dreams.

How did they know how to build a decent dog run, and where did the money come from for the tools, lumber and supplies they needed? Did they actually eat any goat meat? Did they eat any of the chickens Lena so lovingly tended? Did they consider homeschooling for Josie?

While we read about meetings where big decisions are made—do we have pigs, do we go vegan—how were the day-to-day choices about how back-to-the-land to be, made by so many back-to-the-landers, finalized on Figurative Farm? Curious readers wish to know.

*

Amy Whitmore: Creative non-fiction published in Black Dog Review, NB Reader, Vancouver Sun and on CBC Radio Saint John. Summer radio play commissioned by CBC Saint John. Co-winner of Atlantic Film Festival’s Script Development competition, feature category. Mary Walsh chose to read the most eccentric character. Recipient of UBC’s Jacob Zilbur Scholarship for Most Promising Screenwriter and Maxine Sevack Memorial Scholarship in Creative Non-fiction. Currently working on short stories and a novel. Master gardener student, experienced hot air balloon crew, roamer by bike of Calgary’s pathways and byways. [Editor’s note: Amy has reviewed fiction by Sharon Butala, Ron Base & Prudence Emery, W.O. Mitchell and Lenore Rowntree for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Memories of ‘gentle not-quite-back-to-the-landers’”

Re; composting toilets

While initially off-putting, a composting toilet can work well, if properly managed. As emphasised in the novel, urine goes elsewhere. Much like garden composting, the “solid waste” is mixed with other agents (bulky sawdust works well) and needs time to compost (for example, in a sealed container). After two years, it looks very much like soil and has no odour. While most people would still not spread it on a vegetable garden, it’s easily disposed of in the forest. A property that measures 10 or more acres, with a low population density, allows lots of space to deal with composted solid matter.

As a list of subjects ‘missing’ from a work of fiction is infinite, the last five paragraphs of this review make it clear that the reviewer is better qualified to reviewing non-fiction where such a list would be relevant.