Puzzles of the past

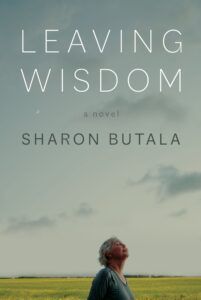

Leaving Wisdom

by Sharon Butala

Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 2023

$24.95 / 9781771872362

Reviewed by Amy Whitmore

*

In 2022 19% of Canada’s population was 65 and older. Retirement age. Who are these people? Wise elders garnering unquestioning respect? People well past their best before date? Humans still stumbling towards self-understanding?

Retirement can mean a new life. The oil and gas guy who becomes a nature conservationist. The guy who finally allows an affectionate woman into his life. The woman who leaves her husband after forty years. The mother who looks back with regret at how she raised her children. An aging child who still struggles in their relationships with aging parents.

In the case of Leaving Wisdom, the fourteenth work of fiction by Sharon Butala (Season of Fury and Wonder), retirement is anything but easygoing. In fact, on her way to her retirement party Judith slips on ice, falls, cracks her skull, and cracks open her life.

When Judith, inflicted by migraines and nausea and barely comprehending the world around her, is released from the hospital, her lover of several years, whom she thinks is going to marry her, tells her he is returning to his wife.

There is a disconnect in Judith’s life, seemingly triggered by her concussion and retirement. She cannot afford to keep her Calgary condo and suffers shouting in her mind whose origin she doesn’t understand. Judith wonders about her running away from her rural Saskatchewan home at 15, never to return. And she wonders why her family never looked for her nor asked her to come home:

‘Sure…,’ Judith said slowly, because behind the tongue and teeth making the words, as she wiped away saliva dribbling minutely from one corner of her mouth, the pieces of an idea were flowing and perfectly together. Thinking of Giles and his real life, she knew now where she would go.

She sells her condo and buys a tiny, decrepit house in her hometown of Wisdom. Not that she wants to be there, but that she feels she must to understand what on earth her life was about. She knows she has to find out who shouted in the night, what kind of a failure as a mother and wife she was.

Memory stabilized, Judith remembers that it was her father who shouted in the night, lashing out and hitting his wife. None of this, nor any emotional states, were discussed as the family that raised her prayed and went to church and scrabbled out a hard living on rocky Prairie soil and prayed some more and did not speak.

Judith must confront her uber-respectable sister and successful farmer brother whom she has not seen in fifty years. The reunion is fraught and rocky:

Back in Wisdom Judith of course cannot avoid bumping into her siblings. But what does this mean to her?

But with her mother and father both dead, what was there to recover? Sam and Abbie had lived their lives; she hadn’t been a part of that. Did she honestly care about the intervening years she had missed? No, not really, she told herself. Just the same old, same old, she told herself…. Her birthright? What the hell was that, anyway? Poverty, ignorance. Parents who, like down-trodden old-country peasants, clasped a god to their bosoms, filled their mouths with Him, He who cared nothing at all for them or they wouldn’t have been so poor and so strange.

Wanting to understand why her father’s shouts, Judith does some hardcore–as in deeply local–research into Prairie border soldiers to unearth her father’s pre-marital life. She comes across little known but true realities of the end of WWII and Alliance soldiers entering a Nazi concentration camp that was her father’s. (This particularly intrigued me, as my father was one of those soldiers but never, ever mentioned it until one night when I was 27, ironing while visiting and he was fairly drunk, but my mother made him stop talking before he told me much).

Ultimately there is so much more than just her father’s story in what Judith reluctantly learns, which traces back to war and the liberation of a concentration camp.

There is a stranger in the park in her hometown with whom Judith briefly bonds, a Jewish man who was tormented out of town by an eviscerated hare hung from his tree, the town still insisting it was just a prank, or outsiders, causes Judith to question yet more aspects of her responses. To question her own lack of action. To deepen her understanding of the reverberations from the Holocaust:

“Good morning. I am Saul Richter. Don’t I know you?”

Had she somewhere heard this name?

“I’m Judith. I used to be a Clemenson.”

“Ahhh,” he said. “I’ve heard the name. You have been here a long time. We are new here, my wife and I.”

Judith knew then who he was: half of the old couple who had had a swastika painted on their fence.

Judith has four daughters, has had two husbands, but has been mostly single for years (excepting most recently her love affair with Giles). Butala reveals this mother’s guilt over how she raised her daughters but also see how she imposes the familial silence and judgement on those daughters.

And how that silence never lets us understand what happened with her husbands. They both left because they “couldn’t take it anymore,” but couldn’t take what? Judith worked full time as a social services worker and came home to cook, clean, iron and help her daughters—what couldn’t those men take anymore?

Her daughters, at least three of four, do not blame Judith for their upbringing the way Judith blames herself. How many of us, our children now gone from home, question, regret, blame ourselves for whatever damage we cause as mothers or fathers?

After Judith learns about her father and the concentration camp—which she does not, in the silent family tradition, find herself able to tell her siblings or children—she hears from her sister that her father is still alive.

Judith must come to terms with what she has been told about her father. She must come to terms with the anger at her sister’s vengeful act of letting her believe their father was long dead. She tries to understand why her religious sister will not fulfill one of their religious mother’s dreams and come to Jerusalem with her while she visits her youngest daughter.

Through the course of the multi-threaded novel Judith’s daughters surprise her. Only her oldest, the most religious, remains the most emotionally remote, possibly even shallow. One she appreciates for her deeply caring and live and let live self. Another with her deeply caring, efficient get-it-done self. The youngest, the most difficult and always troublesome, finally, Judith begins to understand, has come into her own very best self.

An odd, incomplete thread in the novel is the story of what is going on in the house beside her in her hometown. Butala reveals glimpses, and Judith struggled about letting it go or alerting to the police, but the plot is never really developed.

In the end Judith leaves Wisdom, gains wisdom, and cannot again turn her back on her siblings, hard as the new relationships are. Her daughters make painful, joyful decisions that Judith lets herself trust. She lets herself trust the moment with a decision of her own regarding Giles.

While the story, not the language, keeps one reading, nonetheless it is the seemingly plain and effortless language that keeps the story moving and illuminates the insights revealed:

As she drove slowly down the road…she began to relax, although every once in a while she had to wipe her eyes with the back of a hand. After a while, a rare tenderness began to creep through her body. It felt like the sweet flow of warm creek water in summer…..Her father, that terrifying patriarch who never spoke, except in the night when he fell into darkness, had once been a normal man.

*

Amy Whitmore: Creative non-fiction published in Black Dog Review, NB Reader, Vancouver Sun and on CBC Radio Saint John. Summer radio play commissioned by CBC Saint John. Co-winner of Atlantic Film Festival’s Script Development competition, feature category. Mary Walsh chose to read the most eccentric character. Recipient of UBC’s Jacob Zilbur Scholarship for Most Promising Screenwriter and Maxine Sevack Memorial Scholarship in Creative Non-fiction. Currently working on short stories and a novel. Master gardener student, experienced hot air balloon crew, roamer by bike of Calgary’s pathways and byways. [Editor’s note: Amy has reviewed fiction by Ron Base & Prudence Emery, W.O. Mitchell and Lenore Rowntree for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Puzzles of the past”