The way we were

Essay: The Way We Were: Two Friends, Two Historians

by Robin Fisher

*

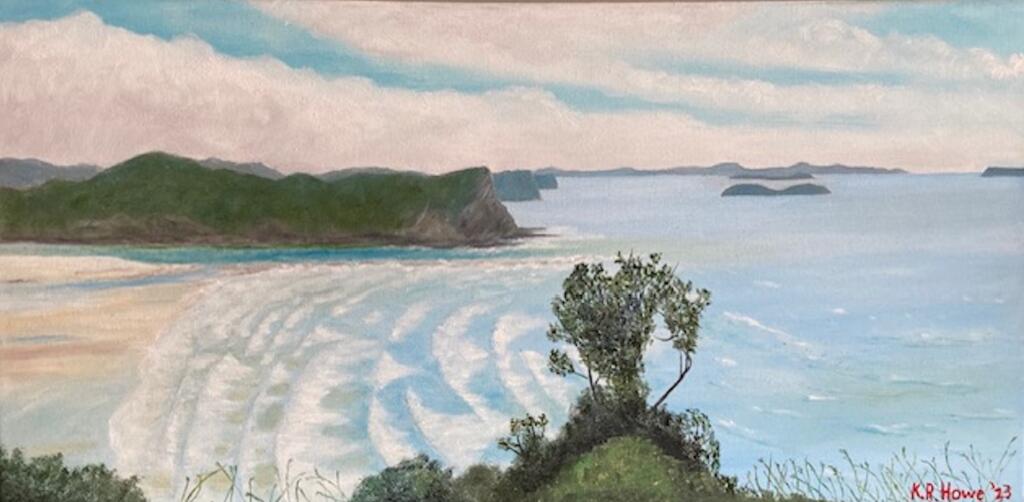

Earlier this year I flew down to New Zealand to spend a few days with my lifelong friend and gifted historian Kerry (K.R.) Howe. It was springtime in British Columbia but winter was coming in New Zealand. We both knew that it would be our last time spent together. It was a tough but affirming few days as we reflected on our lives as historians spent living mostly at either ends of the Pacific. During those precious last few days, we walked some beaches just as we had done many times around the Pacific. I will never forget that last time at Wenderholm Regional Park north of Auckland. In his last days Kerry, drawing on another of his many talents, sent me a painting of Wenderholm that he had done at my request. It arrived on my doorstep just a few days before he left us. It features a very Pacific image of the timeless waves rolling into shore.

Kerry Howe is gone now, at least from this world if not from my life. When we were younger, we were both fond of James K. Baxter, the New Zealand poet and prophet who lived in Jerusalem, up the Whanganui River. As I took those high-altitude flights across the Pacific, I thought more than once of the simple lines of one of Baxter’s early poems about where to find refuge from one’s anger at the arbitrariness of life and death. It is called “High Country Weather”:

Alone we are born

And die alone;

Yet see the red-gold cirrus

Over snow-mountain shine.

I first met Kerry Howe in 1968 in the creaky, colonial house that was then home to the History Department at the University of Auckland. The university was not the oldest but it was the largest and consistently ranked as the best university in the country. Kerry had grown up in the big city of Auckland but close to Narrow Neck Beach, and the beaches and bays of the Hauraki Gulf and north were his natural habitat. I was from the smaller, inland provincial city of Palmerston North with an undergraduate degree from Massey, an agricultural college that became a full scope university in 1964, the year that I started there. I was new to the much larger city and university. We had some differences but we grew to have a lot in common. I remember starting up the stairs to his flat in Ponsonby and seeing a large image of John Lennon peering down at me: I was more of a McCartney fan. Still, we became friends as we worked on our Masters degrees.

The History Department resided in an old house, but there was nothing creaky or colonial about history that we learned. The New Zealand history that we studied then was very much the history of relations between Māori and pakeha, and we were taught by some of the leading exponents of that history like Keith Sinclair and M. P. K. Sorrenson. We both wrote MA theses on missionaries to the Māori under the supervision of Judith Binney, a rising star who had just published a wonderful, innovative book on another early missionary named Thomas Kendall.2 We were thinking about issues that we then called “culture contact” and “race relations”. Our teachers expected us to have ideas and develop interpretations, but they had better be our own ideas and not theirs. And, furthermore, they had to be firmly grounded in evidence. We were given clear directions to the archives. Kerry and I spent weeks in the back rooms of the Auckland Museum where many of the missionary records were housed. And when it came to writing, Judith Binney guided us on the craft of history: as well as being insistent on good, clear writing she drilled us on the importance of impeccable footnotes that would show others the sources of our thinking. We learned so much from our demanding supervisor that Kerry recently remarked that we are both “Binney trained and operated.”

As we finished our Masters degrees we were already talking about where would we go next at a time when it was assumed that a PhD in history would mean going to another country. Going overseas, New Zealanders believed, would broaden the mind. We left for different parts of the Pacific and both soon learned, as the poet Allen Curnow wrote about the discovery of New Zealand:

Simply by sailing in a new direction

You could enlarge the world.3

And so we did. We went our different ways: he to the Australian National University in Canberra to work with the leading lights in Pacific Islands history and me to the University of British Columbia to begin the study of Canadian history. Kerry’s historiographical context was a shift from looking at Pacific Island history through the eyes of explorers and the agents of empires to looking at the experience of those who stood on the shore. A more, that is to say, Island-centred history. In British Columbia, I encountered a historiographical silence when it came to the Indigenous people of the province, as the work was being done by anthropologists rather than historians. We both absorbed these new places and contexts but the practice of history was not a foreign country. We applied the methods that we had already learned as we wrote PhD dissertations that then, to our great excitement, became first books both published in 1977. Our sub-titles reflected our approach to the history and the time in which we wrote. Kerry’s book was The Loyalty Islands: A History of Culture Contacts 1840-1900 and mine Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890.4 We both looked at both sides of the encounters of cultures and paid attention to the agency and actions of Indigenous peoples.

I gave Kerry a copy of my book when we were at a conference in Honolulu. He took it to his hotel at the other end of Waikiki in the evening and phoned me about midnight to tell me, in the spirit of Judith Binney, that he had already found a couple of typos. Meanwhile he had a second book published that same year. In Race Relations Australia and New Zealand he cut loose from doctoral detail and, in less than one hundred pages, compared one hundred years of very different history of cultural relations in the two countries.5 I would later try something similar by looking at Australia, New Zealand, and British Columbia and an article resulted.6 We both argued that the different histories had more to do with the indigenous cultures and responses in each country than it did with the policies and actions of the colonizers.

Our former teacher, M. P. K. Sorrenson, reviewed Kerry’s Race Relations and my Contact and Conflict in The New Zealand Journal of History. Kerry’s “post-doctoral romp” and my published dissertation were very different books yet he suggests that both owed more to Judith Binney than our subsequent doctoral work. The comment holds some truth but is also an exaggeration as both of us learned much from our doctoral mentors and the Australian and Canadian historiographies. Kerry from historians like Dorothy Shineberg and Peter Corris and I worked with Margaret Ormsby and Wilson Duff. Nonetheless, Sorrenson concluded that while Contact and Conflict created a bit of a stir in Canada, New Zealand historians “may not find much to surprise them…”7

By now it was clear that our careers would play out in different places. Kerry had returned home. Well, my home rather than his. He was appointed a lecturer, as junior faculty were then called, at my alma mater, Massey University in Palmerston North. As he frequently reminded me, Palmerston North was not Auckland. It was a smaller town that was not by the sea. Eventually, he would return to his hometown and live once again on his beloved Hauraki shores. I remained the immigrant: from one place and in another, but not quite of either. It would be about ten years before, on a flight back from New Zealand, descending into Vancouver, I finally said to myself “this is home.” I had arrived in Canada the first time without having read a single book in Canadian history, but by now I had done my apprenticeship in the field and in 1974 was fortunate enough to be given a faculty appointment at Simon Fraser University. Perhaps it was just as well that we were not working in the same place. As one of my colleagues at Simon Fraser wrote to Kerry: “How lucky for everybody that you and Robin are not in the same department. You sound identical and we can barely cope with him alone.”8 We began our careers as teachers and publishing historians. We taught in our respective general fields of Pacific and Canadian history and we both developed more specialized courses at more senior levels on inter-cultural relations. When Kerry taught courses on Māori history they were par for the course in New Zealand. When I developed a course on “Canadian Native History” it was the first time that the subject had been taught at Simon Fraser University. We both started thinking about next books and we both launched into different areas of history.

We were separated by the Pacific, but for us that massive ocean, as it did through history, connected as well as separated. I have sometimes wondered if our close friendship was nurtured by distance. We were always in touch: letters typed on aerograms were replaced by emails, we visited each other often and we gave invited talks at each other’s universities. Kerry did not forgive me until his very last email for once dropping him off, the day after he arrived from New Zealand, on the dock at the Tsawwassen ferry terminal at 5:00am on a bitter, wet and windy morning so that he could give a lecture at the University of Victoria. We also met at conferences in warmer places across the Pacific: Canada, New Zealand and Hawaii in between. We had a great moment together in Hawaii when, after a conference on O’ahu, we went across to the big Island for a day and, of course, drove to Kaelakekua Bay where James Cook had met his end. We got to the bottom of the road and realized that we were on the other side of the bay; the only way over to the Cook monument was by boat. Some kids were roaring around the bay, unaware of its dark significance, in what Kerry called a “fizz boat”. They agreed to take us across to spend a few minutes on Cook’s last shore. The Cook monument, along with his reputation, has suffered a fair amount of abuse over the years since but, for us, our time on that spot is a treasured memory. Kerry attended the Cook conference at Simon Fraser University in 1978 and gave a paper on the “The Intellectual Discovery and Exploration of Polynesia” at the Vancouver conference in 1992.9 A year earlier I presented at a conference in New Zealand on sovereignty and Indigenous rights.10 A few years later we both attended a conference in Canberra in honour of the work of the Australia art historian, Bernard Smith. We were big fans of his work. His European Vision in the South Pacific had a huge impact. Beginning with the Cook voyages, he looked through the history of art and ideas at the way Europeans saw the Pacific, its landscape, cultures, and people. He showed how artists tried hard to turn the Pacific into a reflection of Europe but did not quite succeed. We both enjoyed a moment at that conference when, amidst all the sententious academic discussion, Bernard Smith was asked what he thought of post-modernism. He paused for a moment and then said, “Well, it is rather like the mythical whirly bird that flew madly around in ever decreasing circles until it finally disappeared by flying up its own arsehole.” From Bernard Smith we got innovative ideas accompanied with a wicked sense of humour.

But that too was the way we were, even as we learned the distinctions in the sense of humour at each end of the Pacific. At a New Zealand conference there was a reception in honour of Keith Sinclair upon his retirement. Another leading New Zealand historian, W. H. (Bill) Oliver, who like Sinclair was also a poet, rose to say a few words, but they were not very poetic. “I am not sure what to say,” he began, “for what more can be said about Sir Keith Sinclair that he himself has not already said.” That kind of humour, laced as it was with irony, I soon learned did not fly so well in Canada. Towards the end of my first academic year, I wrote an essay in Margaret Ormsby’s graduate seminar at UBC about Indigenous land policy in colonial British Columbia. I commented briefly on Frederick Seymour, the Governor of British Columbia after James Douglas. His approach to First Nations people relied more on facile ceremonies than any recognition of their rights to their own land. Seymour died on the naval vessel Sparrowhawk when he was up the coast to deal with a “disturbance” with that other fine advocate of Indigenous rights, Joseph Trutch. I wrote that, with his passing, Seymour made his most important contribution to British Columbia history. Oh dear! That did not go down well at all. Margaret Ormsby insisted that it be expunged as I had not done sufficient study of that father of British Columbia. She was right in one sense. I had not realized that she was working the Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry on Seymour that was rather more laudatory.11 In fairness to Margaret Ormsby, she did accept my much more evidence-based argument about Trutch’s racism and his dreadful Indian land policies even though the case that I made would, in time, ruin the reputation of another important figure in early British Columbia history.

When Kerry and I spoke and wrote to each other, our conversations were full of irony, cheek, and suitable outrage. We believed that directness could take us to the heart of any matter. In our antipodean way, we were direct and opinionated with and about each other, and about history, historians, and historical writing. Kerry was of a more philosophical bent than me. He once excitedly insisted that I had to read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.12 He was fascinated by the thinking in that book about the concept of quality and so he was very disappointed in me when I responded by buying a motorcycle. Motorcycle riding, I thought, was a quality experience but that was not what Kerry had intended.

We both decided to move on and look at different kinds of history from the Indigenous/newcomer relations where we had started. When I began work on a biography of a politician Kerry was shocked and appalled. His response drew upon T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, a poem that is about, among other things, aging and indecision:

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.13

I guess I had, earlier and often, given him my opinion that there were already too many political biographies written by Canadian historians. “Prufrock has got nothing on you, mate!” he wrote.14 I did not, however, reverse my decision. Soon he too was working on a biography. We both had misgivings. But we also had moments of belief about the value of biography: that quintessential kind of history, telling the story of an individual who made a difference.Our books were both published on the same day, though Kerry, who was not the least bit competitive, claimed that his came out first because New Zealand is a day ahead of Canada. Mine, Duff Pattullo of British Columbia, was about the reformist Premier of the Province in the 1930s.15 Kerry’s Singer in a Songless Land, was a life of Edward Tregear, a widely published intellectual, a poet, an authority on Māori and Polynesian studies and, as Secretary of Labour, author of the world’s most advanced labour legislation. Kerry had changed his tune by the time he sent me a copy of his Tregear biography; it was inscribed “With thanks for the inspiration, or challenge…”

Whether inspired or challenged, he had not lost his critical skills, this time when I lapsed into purple prose. Describing Pattullo’s early experience in the Yukon, I wrote: “Like the wild flowers of the north that bloomed so brightly because the season was short, Dawson also faded fast.”16 I cannot count the times that “the wild flowers of the north” were brought back to haunt me. History repeats! Oh yes, and I was once told, in a tone that was not to be gainsaid, never, ever use an exclamation mark. We both vowed never to write another biography and Kerry kept his word. When I later started work on another biography, even about someone named Duff, Kerry’s initial reaction was very pointed.

He was also suitably scathing when my university career took me in the direction of administration, aka the dark side. I attempted to argue that the historian’s abilities – hoovering through vast quantities of documents, separating the important from the unimportant, understanding motivation and figuring out why things happened – all applied to university administration. That is why many university administrators were historians. Kerry was unconvinced. Crikey, you must be up the boohai shooting pukekos.17 Rough translation: you are out of your mind. So, I had another go at making the case. Was it not better to have academics, even historians, running things rather than non-academic administrators? No way, he would not buy it. For Kerry, most administrators were dubious characters, more interested in power than people, so he often cautioned me in case I became like one of those. His admonitions rang in my ears whenever I felt that I was becoming too bossy. Only occasionally did he allow that the opportunity to play a role, as it turned out, in the establishment of two new universities might have creative possibilities.

Once we briefly worked together at one of those new universities. I had moved from Simon Fraser to the University of Northern British Columbia to take up the opportunity to build a new history department. Kerry accepted my invitation to come north and teach for at least a semester and see how he liked it. He taught New Zealand, Australia, and Pacific history, subjects not usually covered in Canadian departments. The University of Northern British Columbia, like Simon Fraser, began with the aspiration to be innovative and different and then became more conventional as time went on. Kerry was with me during the first semester of full operations at UNBC and together we felt the exhilaration of starting a new department in a new university. As I was working on a new history department he was thinking about environment and culture. To my disappointment, after a semester he decided to return to warmer climes in the south. His adaptation to the Prince George winter had not been flawless. After he jumped out of the hot tub and made snow angels in my back yard, I told him that most Canadians did them with their clothes on. Still his sojourn in that northern cold climate did get him thinking about Canada’s “vast, cold landscape” and its influence on Canadian culture. As he wrote: “It soon dawned on me that the Canadian “wilderness” and the “cold” were as much ideas as some sort of physical actuality.” That idea led him into the vast literature on the influence of environment on human personality and culture and renewed his thinking “about Western responses to “my” temperate and tropical part of the world – Oceania.” The book that resulted was called Nature, Culture, and History: The Knowing of Oceania. It began with the highly overgenerous dedication: “For Robin Fisher (il miglior fabbro) who led us into the cold.” I had earlier dedicated my Vancouver’s Voyage: “For Kerry Howe, in recollection of Pacific Shores.”18 I would do better in a later book.

While, as administrator, I wrote memos and academic plans, Kerry continued to write books. He had already published Where the Waves Fall, a general history of the Pacific from first settlement by Pacific Islanders to colonial rule. He wanted to overcome what he called “monograph myopia,” where every island has its own history book, and explore the connections between those tiny dots in the vast ocean and the overarching themes of their history. He then took up the topic of the first settlement of the Pacific again in The Quest for Origins, in which he looks at the factual evidence and the various ideas about from whence and how the Pacific was peopled.19

His next book arose from other enthusiasms and experiences on Pacific waters. Coastal Sea Kayaking in New Zealand was based on his kayaking of long stretches of the North Island and the sounds of the northern South Island. He had, as he noted, “paddled quite a few nautical miles and almost sorted out the meaning of life.”20 Then he got a “real boat” and took up sailing. With his next book he came full circle, back to his origins and his close connection with place. To the Islands is about Exploring, remembering, imagining the Hauraki Gulf.21 With this book sailing and scholarship became one. It had been ever thus but now it became perfectly clear. It was also about the history of the area and the impact that the human history has had on the environment. Kerry had always maintained that history was, in large part, autobiography and this was his most autobiographical book. His joy in sailing those waters is mixed with sadness at how polluted they had become. The text is interspersed with his sketches, in the tradition of George Vancouver’s midshipmen, of the shapes of coastlines and landforms.

By now the landscapes of our lives were changing as we both headed into the, for us, uncharted waters of retirement. Sailing and painting were two of Kerry’s retirement pursuits. When I finished my last full-time position at Mount Royal University, Kerry sent some comments to be read at my retirement function. He allowed that “even I have to admit that he’s done quite well” as an administrator, but what he really hoped was that I would “come back into the light” and write some history.22 I felt that I should not disappoint him so, along with doing other things, I started work on a biography of the anthropologist, Wilson Duff. It would take a long time and Kerry was not a patient person. After To the Islands he did not publish anything major but expected me to provide him with something to read and evaluate. “What the hell are you doing and when will I get the next chapter?” he would demand of me. As I was working on the book Kerry was a constant source of helpful, and clear, criticism that was warranted, and positive feedback that was both welcome and needed. The artist in him generated particularly strong opinions on possible cover designs and I breathed a sigh of relief when the publisher, unknowingly, followed his advice.

As I was working through Wilson Duff’s ideas about meaning in Haida art, I became intrigued with his ideas about a bentwood box with a design that was so abstract and complex that Wilson and Bill Reid called it “the final exam.” Wilson believed that the box depicted Raven and that thought took him to a story of Raven creating the world as recorded by the ethnographer John Swanton. In the story an old man instructs Raven, by handing him two pebbles, on the creation of Haida Gwaii: that is the world. As he passes over the means of creation, the old man says to Raven “I am you.”23 Wilson Duff thought about that, for him, most meaningful phrase for the rest of his life. When my book was finished and Kerry received his copy, his generous assessment meant a lot to me. No feedback was more valued. Kerry liked the book so much that he did not look for typos! He particularly approved of the chapter on “Meaning in Haida art.” With that book, I felt like I had passed the final exam with Kerry Howe. He was one of two pebbles: that reciprocal creativity that was essential to anything that I had achieved over the years. That is why my book, Wilson Duff: Coming Back, a Life, is dedicated to “Kerry Howe because I am you.”

When I had made the arrangements to see Kerry for the last time, he stipulated that we would not dwell on his declining health but would rather talk as we had always done as if nothing were different. After all, he wrote, there would be “lots of history to be worked through, the epic life and times of two legends in our own minds.”24 As we talked about history, knowledge and knowing, some lines from T.S. Eliot that seemed to resonate:

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information25

“Choruses from ‘The Rock’” was an Eliot poem that we had paid less attention to than others perhaps because it seemed less relevant when we were younger. Now they said so much about the state of the world, and of history. The lines were drawn to our attention because we were reading Simon Winchester, Knowing What We Know and he cites the Eliot lines in the front matter.26 Winchester’s book actually turned out to be more about the mechanics of knowledge than the nature of knowledge. We agreed that Kerry had written more perceptively about nature and knowledge and the nature of knowledge his short introduction to Nature, Culture, and History.

Turning to less esoteric matters, we held a seminar between us on a new book that had just come out on the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document.The intent of the Treaty of Waitangi was different from Canadian treaties with Indigenous people in that it was designed to confirm Māori rights to land and governance. The subsequent settler history, however, did not ratify that intent. Behind Ned Fletcher’s prosaic title, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, is a huge book based on prodigious primary research. The kind of history that we had aspired to but does not get published much these days. It all leads to his concluding sentence on page 529. Fletcher writes of the Treaty that: “It was conceived, written and affirmed in good faith.”27 It was not a disingenuous hoax as more extreme interpretations have held. Rather Britain was reluctant to intervene in New Zealand but did so to protect Māori interests and to control the settlers. Alas, the road to hell was paved with good intentions.

We also spent time towards the end, both by e-mail and in conversation, about a fairly recent book that actually had something new to say about Captain Cook. Scholarship on Cook and the exploration of the Pacific is as vast as the ocean itself. Historical writing about Cook has been through all the academic fashions and fads since the New Zealand historian, J.C. Beaglehole’s, life’s work culminated in his 1974 biography.28 Yet we had both been thinking for some time that nothing startling and new was being written about Cook. Then Kerry found, and had me read, a book by the Australian Margaret Cameron-Ash called Lying for the Admiralty.29 The centrepiece of her argument was about why Cook did not record the existence of the magnificent Sydney Harbour in his journal. It is one of the largest, most sheltered harbours in the world so why did he miss it? Well, in fact he did not miss it. He saw Sydney Harbour by walking over to it from his anchorage in nearby Botany Bay. He did not write about in his journal in order to prevent other European rivals, particularly France, from finding out about it. He concealed it for strategic reasons by lying for the Admiralty and the British Empire. Cameron-Ash also had other examples, particularly on the New Zealand coastline, of Cook manipulating geographic information. Kerry was more convinced by her argument than I was, but it certainly was a new interpretation of Cook. For a moment we thought that it would be neat to get a group of Cook scholars together at a conference, as in the past, to examine and debate the Cameron-Ash evidence and thesis. But then, hold on, there are no longer the scholars doing that kind of evidence-based work on Cook and, moreover, it really does not seem to matter anymore.

We acknowledged that there were other senses in which things were now not the way they were. During our last days together, we spent time reminiscing about how easy we had it compared to many of those in generations that followed. We were educated in a system in which, if you stayed on in secondary school for another year after passing your University Entrance exams, university was free. Fewer students went to university than today, but those who qualified paid no fees. We had stimulating teachers who took pleasure in ideas. History, and the humanities, generally were still valued, certainly in our universities and to some extent in society. New Zealand tended to have more of a practical disposition and I was sometimes asked why I did not give up all that university nonsense and take on an apprenticeship in a useful trade. Yet there was a grudging recognition of the need for social criticism and we relished the role. I remember at my BA graduation ceremony the Head of the History Department, W.H. Oliver, up on the stage and looking daggers when the local Member of Parliament said, in sonorous tones, that the function of the university was to serve society. We knew better than that, we were society’s critic, drawing its attention to what we believed were the lessons of the past. We readily got scholarships to study overseas for our PhDs and we both had partners who worked while we completed degrees. We graduated with three degrees debt free. We never faced barriers, as others would do, because of our social background, gender, ethnicity, or the coming scarcity of university positions. We both got jobs in universities before the boom came down and at a time when universities were comparatively well funded. We taught in an environment where history seemed to matter and there was support for research and publication, though there was much more support available to me in Canada than to Kerry in New Zealand. We saw each other at conferences, and beaches, all over the Pacific. And people read serious, evidence-based, history. We had it good.

Long distance friendships are punctuated by the joy of greeting and the sorrow of parting. I have always been struck by the fact that the words for welcome and departure in te reo Māori are very similar: haere mai and haere rā. You cannot have one without the other. Kerry and I had agreed that at the end of our last visit there would be no fuss when the time came for me to leave. It would be the same as it always was: a quick “see ya” and one of us would be on our way. So, when he pulled up at the Auckland airport, Kerry did not get out of his car. Just a “see ya” then I turned to wave as I went through the closing doors of the international departure terminal.

When all has been said and done, there is still nostalgia. It is an old man’s game though. Towards the end, Kerry Howe and I also wondered:

Can it be that it was all so simple then?

Or has time re-written every line?

If we had the chance to do it all again

Tell me, would we?

Could we? 30

*

- James K. Baxter, “High Country Weather,” Collected Poems, (Wellington: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 34. ↩︎

- Judith Binney, The Legacy of Guilt: A Life of Thomas Kendall (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1968). ↩︎

- Allen Curnow, “Landfall in Unknown Seas,” in A Small Room with Large Windows: Selected Poems (London: Oxford University Press, 1962), p. 33. ↩︎

- K.R. Howe, The Loyalty Islands: A History of Culture Contacts 1840-1900 (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1977) and Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1977). ↩︎

- Robin Fisher, “The Impact of European Settlement on the Indigenous Peoples of Australia, New Zealand and British Columbia: Some Comparative Dimensions,” Canadian Ethnic Studies, XII, no.1 (1980), pp.1-14. ↩︎

- K.R. Howe, Race Relations Australia and New Zealand: A Comparative Survey 1770s-1970s (Auckland: Longman Paul, 1977). ↩︎

- M.P.K. Sorrenson, “Review,” The New Zealand Journal of History, vol.12 no.2 (October 1978), pp.168-70. ↩︎

- Edward Ingram to Kerry Howe, 15 January 1987, Fisher personal papers. ↩︎

- In Robin Fisher and Hugh Johnston (eds), From Maps to Metaphors: The Pacific World of George Vancouver (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1993), pp.245-262. ↩︎

- In William Renwick (ed.), Sovereignty& Indigenous Rights: The Treaty of Waitangi in International Contexts (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1991), pp. 49-66. ↩︎

- Margaret Ormsby, “Frederick Seymour,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1976) Vol. IX, pp.711-717. ↩︎

- Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values (New York: William Morrow, 1974). ↩︎

- T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Collected Poems 1909-1962 (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), p. 14. ↩︎

- Robin Fisher, Duff Pattullo of British Columbia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991) and K.R Howe, Singer in a Songless Land: A Life of Edward Tregear 1846-1931 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1991). ↩︎

- Kerry Howe to Robin Fisher, 19 June 1979, Fisher personal papers. ↩︎

- Fisher, Duff Pattullo, p.77. ↩︎

- The boohai is the back blocks, or the back of beyond, and the pukeko a flightless land bird. The phrase has connotations of being lost, possibly in the head. See David McGill, Up the Boohai Shooting Pukakas: A Dictionary of Kiwi Slang (Naenae: Mills Publications, 1988) p. 18 ↩︎

- K.R. Howe, Nature, Culture, and History: The “Knowing” of Oceania (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000), p. v and ix and Robin Fisher, Vancouver’s Voyage: Charting the Northwest Coast, 1791-1795 (Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 1992), p.v. ↩︎

- K.R. Howe, Where the Waves Fall: A New South Seas Islands history from first settlement to colonial rule (Sydney: George Allen & Unwin, 1984) and K.R. Howe, The Quest for Origins: Who first Discovered and Settled New Zealand and the Pacific Islands? (Auckland: Penguin Books, 2003). ↩︎

- Kerry Howe, To the Islands: Exploring, remembering, imagining the Hauraki Gulf (Auckland: Mokohinau Islands Press, 2016). ↩︎

- Kerry Howe, Coastal Sea Kayaking in New Zealand: a Practical Touring Manuel (Auckland: New Holland, 2005), p. 8. ↩︎

- Kerry Howe, “A tribute from down under (or, some things you might not know), Fisher personal papers. ↩︎

- John R.Swanton, Haida Texts and Myths Skidegate Dialect (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1905), pp. 110-12 and Robin Fisher, Wilson Duff: Coming Back, A Life (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2022), pp. 249-250 ↩︎

- Kerry Howe to Robin Fisher, 25 April 2023, Fisher personal papers. ↩︎

- T.S. Eliot, “Choruses from ‘The Rock’”, Collected Poems, p.161. ↩︎

- Simon Winchester, Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge, From Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic (New York: Harper, 2023). ↩︎

- Ned Fletcher, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 1922), p.529. ↩︎

- Margaret Cameron-Ash, Lying for the Admiralty: Captain Cook’s Endeavour Voyage (Kenthurst NSW: Rosenberg, 2018), particularly pp.163-174. ↩︎

- J.C. Beaglehole, The Life of Captain James Cook (London: the Hakluyt Society, 1974). ↩︎

- Marvin Hamlisch, Marilyn Bergman, and Alan Bergman, “The Way We Were,” (Arlovol Music, Colgems-emi Music Inc., Vibzelect Publishing). ↩︎

*

Robin Fisher taught and wrote history as a faculty member at Simon Fraser University before he moved into university administration and contributed to the establishment of two new universities: the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George and Mount Royal University in Calgary. His books include Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (UBC Press, 1977; second edition, 1992) and Duff Pattullo of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 1991). He was the 2022 Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing for Wilson Duff: Coming Back, A Life. Editor’s note: Robin Fisher has reviewed books by Gordon Miller, Art Downs, Richard Boyer, William Frame & Laura Walker, Michael Layland, and Peter Cook, Neil Vallance, John Lutz, Graham Brazier, & Hamar Foster for The British Columbia Review, and contributed a popular essay in May 2021, “The Noise of Time” and the Removal of History?

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “The way we were”

Bravo !

Thank you for this – such an insightful analysis of Canada and New Zealand’s approaches to the interpretation of Indigenous/Settler relations. As a history graduate of Te Herenga Waka (VUW) and an educator and student of BC Regional history, I was delighted to see this.