Life’s seasonality, in two poem collections

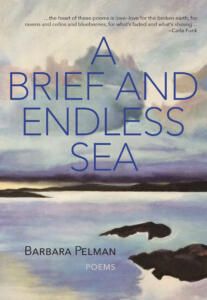

A Brief and Endless Sea

by Barbara Pelman

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2023

$20.00 / 9781773861258

doom eager

by Karl Meade

Salt Spring Island: Rainbow Publishers/Raven Chapbooks, 2023

$22.95 / 9781778160349

Reviewed by Joe Enns

*

Two Vancouver Island poets draw on vast landscapes as they examine grief and mortality through life’s seasonality.

Two Vancouver Island poets draw on vast landscapes as they examine grief and mortality through life’s seasonality.

Victoria-based poet Barbara Pelman (Narrow Bridge) uses echoed lines, borrowed voices, and close personal imagery to provide a real sense of the poet’s lived experience as ocean tides through a progression of seasons in A Brief and Endless Sea, her fourth book of poetry.

Throughout this collection of fifty-six poems, Pelman reflects on loss and the loneliness of aging—“a cycle completed. We women who lost a father / in winter, gather our memories and honour them.” She relives memories through echoed language (“to comfort, but what words / I offer are forgotten in an instant, / only the frantic tape repeated and repeated”), which is apparent in her imagery and form, often using echoic line forms such as the villanelle, pantoum, and glosa. The cycling and reiteration is introduced effectively in the dedication, a villanelle comprised of lines taken from Patrick Lane poems: “White moon. The tide. All things receding. / How hard it is to save everything.”

In A Brief and Endless Sea, Pelman saves what she loves through memoir poetry and creates a porthole for the reader to experience beautiful and meaningful moments.

The paradoxical book title, A Brief and Endless Sea, does well to represent Pelman’s poetry as a fleeting effort to recapture the feelings of past romances, family, and the loss of loved ones: “we watched stars from the porthole, / that attic ship that sailed / in a brief and endless sea.” How can something be both brief and endless? Perhaps in the same way that life—“nothing to excrete or mobilize or measure / no other function but pleasure”—can be expressed in a brief pattern of poetic lines, “both the toucher and the touched / no other function.”

Pelman doesn’t write in solitude. She gathers the voices of others throughout her work, either through borrowed lines or epigraphs. Many of the poems are a glosa form, where the poet features a quatrain from another poet’s work (poem or song) in the epigraph; the closing line of each stanza is a line from the borrowed quatrain. The technique creates a layered complexity as the closing lines become pivot points and connections between the two works (“how do these stories end? Total surrender”).

Readers feel the gravity at those lines, and a familiarity, while also sensing other abstractions that have influenced the poet. Though an over-reliance on other poets could come across as derivative (“Two souls becoming one. Such drivel, my friend says. // Still, I am drawn”), readers perceive that Pelman purposely employs the external forms as a connection to the past (“A woman sitting alone on a fire escape, / playing jazz to the hot summer night”) and an antidote to loneliness by finding pleasure in others.

doom eager, a chapbook by Salt Spring Island writer Karl Meade (Odd Jobs), examines sacrifice and loss through the connectivity between our bodies and the broader geology.

doom eager, a chapbook by Salt Spring Island writer Karl Meade (Odd Jobs), examines sacrifice and loss through the connectivity between our bodies and the broader geology.

Meade links language to terrestrial transitions (“…what the earth knows: / core to crust, mouth to lung // the rupture comes…”) and creates lines of strong rhythm with holes and hills, ridges, and rifts.

In “summer rift,” the speaker seems to be speaking to God (after the Book of Job) and writes: “all your best plates made the earth // eat itself for show.…” This dynamic energy of elements cleaving and spawning (“The heat, the waves, consumed and consuming”) is prominent throughout the collection.

Meade explores how meaning is revealed when things end. Death and loss are inevitable: “we are not just death’s creeping advance, we are the open terrace of fracture.” Again addressing God in “summer rift,” Meade writes, “You stop, we die. You work, we die,” but in the midst of these slow tectonic forces, Meade searches for meaning by remembering loved ones whose lives have ended (“Bury or bones—we dream them back”).

Recall is especially important in the section titles “de mens” where Meade repeats and reiterates variations of the question of “what it means.”

“De mens” is one of the most accomplished sections in the collection, both because of the complexity of word choice and variation, and because of the change in form. In the Preface, Meade states that most of the poems in the collection are ghazals, though without the rhyming or repetition pattern, or disconnected imagery between stanzas (when does a ghazal stop being a ghazal?).

While the first poem in the book, “spring ease,” uses ghazal techniques most effectively with shifted rhymes, rhythm, and repetition with variation (“of the noon. The moon, at noon. / Let’s dance by the light of the noon”), the other couplet-formed poems seem to be at odds with the geological motif. Meade connects language to the unpredictability of life and jagged abiotic forces (“the torrent of letters we clutch like shrapnel…” and “your young volcanic mouth…”), yet the strictness of the couplets and predictability of the spaces don’t match the content.

The form changes in the “de mens” section, however, and that builds strong realizations and a deeper impression. For example, the poem “what de mentia” closes with: “…the holes / are just space // the words leave /// for you and me / sun and moon // I remember now /// how it ends / what it / means.” Meade uses shortened line lengths and scattered stanzas to convey the memory blanks of someone with dementia; he intersects those with the realization that the meaning of things comes when they end.

Meade’s strengths are his memorable use of rhythm and sound, and his ability to close with aphorism and reflection that will leave a reader lost in thought (“…you spawn stones // of geodetic lust…”).

A noteworthy example of rhythm and sound is in “what it means,” where Meade writes, “…ragged veined victims of your thousand-day / lymph war.…” The rhythm, rhyme, and alliteration here stands out and etches deeper the imagery of life-altering medication. The eponymous poem, “doom eager,” closes with, “because the only cure / for the wound / is the wound.” The aphorism sums up the rationale for the preceding poems and leaves readers pondering the meaning at the end of this image-rich and complex chapbook.

*

Joe Enns is a Canadian writer, painter, and fisheries biologist on Vancouver Island. His writing has appeared in The Dalhousie Review, FreeFall, The Fiddlehead, GUSTS, and Portal Magazine, and book reviews in The Malahat Review and The British Columbia Review. Joe has a BA in Creative Writing and a BSc in Ecological Restoration. [Editor’s note: Joe recently reviewed M.W. Jaeggle, Ali Blythe, Emily Osborne, Will Goede, and Evelyn Lau for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Life’s seasonality, in two poem collections”