1967 ‘A long artistic tradition’

Pacific Voyages: The Story of Sail in the Great Ocean

by Gordon Miller

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2023

$59.95 / 9781771623476

Reviewed by Robin Fisher

*

This is a great book about a great ocean and the tiny ships that made it manifest. The literature on the exploration of the Pacific, it sometimes seems, is as vast as the ocean itself. These historical seas are well sailed so new discoveries, like the islands that dotted the Pacific were in the past, are hard to find. That is why Miller’s book is such a pleasure.

This is a great book about a great ocean and the tiny ships that made it manifest. The literature on the exploration of the Pacific, it sometimes seems, is as vast as the ocean itself. These historical seas are well sailed so new discoveries, like the islands that dotted the Pacific were in the past, are hard to find. That is why Miller’s book is such a pleasure.

There have been other books about sailing ships in the age of exploration and the lives of the crews aboard those vessels. Books like N.A.M. Rodger’s The Wooden World describe shipboard life in the eighteenth century British Royal Navy.

There are many books about the people who followed their “Dream of Islands” into the Pacific, their experiences, what they learned, and how it changed them. But Miller’s book is about the personalities of the sailing craft themselves as they encountered the Pacific: the brigs and barques, the canoes and clippers, the sloops and schooners and, perhaps most of all, those properly called ships in the age of sail. Ships like Cook’s Endeavour: a working ship, bluff with a shallow draft, three masted and square rigged, not flashy but sure and solid. Ships that endured the long voyages out of Europe to the other side of the world. Ships that were, at the same time, so tiny and infinitely insignificant as they sailed an ocean the covered a third of the earth’s surface.

Miller’s text provides an account of the many voyages made under sail. I like the fact that he starts with the first voyagers who ventured into the Pacific “about 1,000 years before the foundation of Rome.” The original Pacific people who sailed, explored, discovered and settled the islands of the ocean. Not by accidental, drift voyages, as historians used to believe, but by deliberate navigation. Centuries later the sailing vessels from Europe arrived.

Miller’s accounts of the newcomer voyages are really even handed and include all the nations that were involved, beginning with the Spanish. Ferdinand Magellan, who was Portuguese but sailed for Spain, sailed away with five small ships. They had a terrible time crossing the Pacific and only one of the five completed the voyage, and without Magellan. Many of the early Spanish vessels took a pounding in the Pacific. Initially they travelled in straight lines, back and forth, in the interests of trade. Then they followed meandering routes looking for islands or imagined southern continents. For a while the Pacific was a Spanish Lake. In 1578 Drake’s Golden Hind burst through the Strait of Magellan to bring a British presence into the Pacific. Unlike many historians, Miller does justice to the pre-Cook British voyages as he also does to the vessels of other nationalities: particularly Dutch and French but also Portuguese. Nor does he ignore the north Pacific, beginning with Russian explorers and fur traders and covering the Spanish, Cook, Vancouver and the maritime fur traders. Other resources besides sea otters brought sailing vessels to the Pacific: copra and sandalwood in the south seas, whales and seals throughout the Pacific and lumber from the northwest coast. With the development of trade and commerce, time became money and there was more demand for faster ships leading to the development of clippers, sleek and full of sail, they were designed to go long distances and at rapid rate of knots. The quest for speed and larger cargoes eventually meant that sail was replaced by steam.

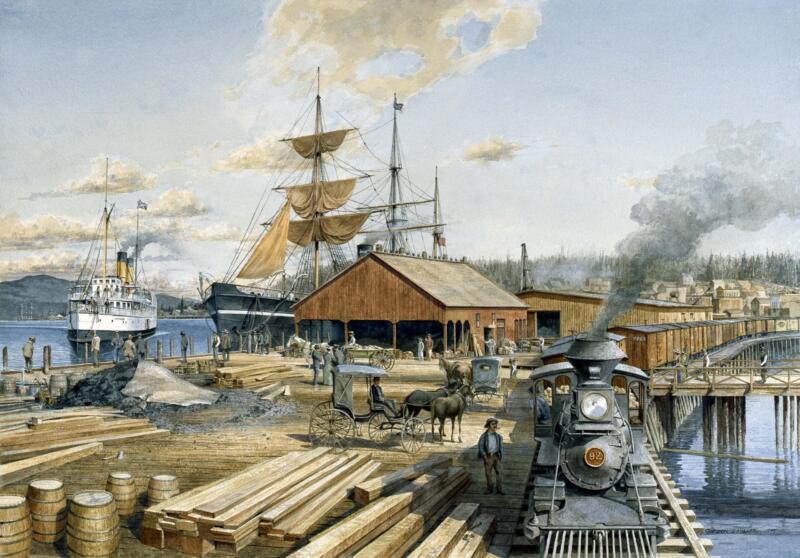

Miller’s text covers a lot of ocean, describes many vessels and voyages and provides a fine summary of the history of the Pacific in the age of sail. But the stunning thing about this book is Miller’s paintings that are lavishly reproduced. They provide a vivid sense of what it was like to face the Pacific under sail.

There is a long artistic tradition, going back to the artists on the exploring expeditions, of depicting sailing ships in the Pacific. The early artists tended to be more interested in landforms and Indigenous cultures and, when they depicted the ships, they were often at anchor in bucolic bays with Indigenous people in their canoes around them. Most of Miller’s paintings are of ships alone on the open ocean. There are some exceptions. One is an enchanting image of sea otters lolling on their backs amongst the kelp unaware that their nemesis in the form of a sailing ship is lurking in the background. There are some paintings of ships riding at anchor in calm waters. The view of five whaling vessels in the Lahaina Roads and the lush, green Maui landscape gave me a jolt as I thought of the history that was wiped out there this summer.

Many of Miller’s paintings convey the power of the Pacific and vulnerability of the sailing vessels. Magellan named the ocean Mar Pacifico, or peaceful sea, but often it was anything but. The storms could be ferocious, without mercy, particularly if the ships were unsuitable or poorly built and fitted out. Look at Miller’s image of Drake’s Golden Hind looking ragged and worn, half submerged in a trough between waves that rise as high as the topmast. There is a shaft of light between the storm clouds perhaps suggesting better weather to come. We then see that Drake did find calmer waters and a chance to refit in Drakes Bay on the California coast. But we also see the image of William Bligh and eighteen of his crew in a small launch scudding before a following sea in a storm. They seem on the brink of disaster. Bligh’s 4,000 mile odyssey, from where they were turfed off the Bounty near Tonga to Dutch Indonesia, was a marvel of eighteenth century navigation. Other sailing ships did not survive. Even the well prepared French scientific expedition led by La Pérouse, after exploring the length and breadth of the Pacific sailed from Botany Bay on the east coast of Australia and was never heard from again until the remains of his two vessels were found years later on an island in the Solomons. Perhaps the most poignant scenes in this book are those of ships that did not make back home. They are depicted, having run aground on a Pacific shore, derelict and rotting away. These lost ships were part of early Spanish expeditions.

Such losses became fewer as European captains and crews learned from experience and got better at sailing the Pacific. Early disasters throw later achievements into relief. Those who successfully sailed the Pacific were celebrated at the time and, although with increasing reservations about their impact, have been remembered since. The ships themselves not so much. They are mostly gone without a trace. They often met sad ends and were forgotten. Cook’s Endeavour was, we believe, scuppered and lies at the bottom in Newport harbour in Rhode Island.

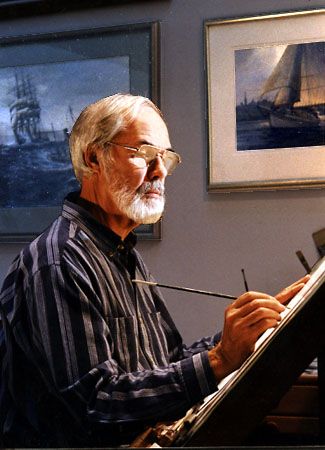

Miller’s Pacific Voyages celebrates the vessels themselves and brings them back to life. He concludes with an appendix of detailed plans of the structures of many of the sailing ships. It shows the sophisticated technology of sailing in the Pacific and the ships that made it possible. His text provides a summary of all the various voyages. Most of all, the paintings are superb. Miller is an accomplished maritime artist. With both accuracy and imagination, he paints the sailing vessels against the great ocean in all its moods.

*

Robin Fisher taught and wrote history as a faculty member at Simon Fraser University before he moved into university administration and contributed to the establishment of two new universities: the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George and Mount Royal University in Calgary. His books include Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (UBC Press, 1977; second edition, 1992) and Duff Pattullo of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 1991). He was the 2022 Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing for Wilson Duff: Coming Back, A Life. Editor’s note: Robin Fisher has reviewed books by Art Downs, Richard Boyer, William Frame & Laura Walker, Michael Layland, and Peter Cook, Neil Vallance, John Lutz, Graham Brazier, & Hamar Foster for The British Columbia Review, and contributed a popular essay in May 2021, “The Noise of Time” and the Removal of History?

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1967 ‘A long artistic tradition’”

I have always been fascinated with Gordon Miller’s paintings, He should be recognized as an artist on an international scale. I only wish all those early maritime publications I have on my book shelfs could have had the appropriate Gordon Miller paintings on the first page.