1966 The brutal stuff of life (with a side of contentment)

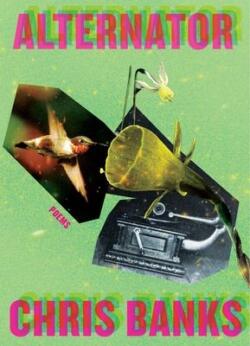

Alternator

by Chris Banks

Madeira Park, Harbour Publishing, 2023

$19.95 / 9780889714588

Reviewed by Marguerite Pigeon

*

Chris Banks has called his new book of poetry Alternator. An apt title, to this reader, as the word speaks not only to this current work, but to Banks’s overall way of writing.

Chris Banks has called his new book of poetry Alternator. An apt title, to this reader, as the word speaks not only to this current work, but to Banks’s overall way of writing.

A car’s alternator turns mechanical energy into electrical charge. Spark plugs use the charge to ignite combustion. Just so does Banks convert experience: in comes the matter of daily life; out, onto the page, go energetic bursts of memory, observation, cultural detail, and idiomatic turns, sparking poetry.

Banks has transformed myriad facets of life in this manner, producing six books. Busy, intense, wry, and sharp, his writing offers readers new angles on everything from science, philosophy and poetry to childhood and greed, all with an eye to human folly. Emotionally, his works reverberate with restlessness, depressive tendencies, ironic perspective, and, sometimes, cynicism.

But in Alternator, his seventh offering, Banks’s output is unexpected. While the same, often brutal, stuff of life is coming in, what’s emerging is new: contentment.

From the book’s third section, “Mirror Bouquet,” made up of 24 untitled sonnets:

I regret nothing anymore, not old selves that fled

in the night and never came back, not the fallen blossoms

left shredded in the yard, not the blood and beaten language

Those last words hint at the work—near violent—of keeping a poetic alternator going over many years. The transformation into verse of lost relationships, lost youth, substance use, and cultural matter seems to be, at once, Banks’s way of life, and a tax on it: “there is a red coal stuck in my mouth that I wish to spit // out” (from the fifth sonnet).

Early in Alternator, the consciousness we encounter is edgy from effort, a clearinghouse of changing perceptions. There, a long poem, “Core Samples of the Late Capitalist Dream,” surveys environments of decline in staccato couplets:

Emergency rooms and dive bars are filling up

with February’s patrons. Strangers huddle

outside a chain restaurant waiting for a taxi

to shuttle them home to bed. A few homeless

sleep in heated ATM lobbies. People are dying.

People whose last touch is a paramedic’s hand.

“Core Samples” turns these perceptions into scaffolding for a responsive, contemporary selfhood. Not clearly Banks’s own, the “I” in the poem links to spaces and actions of our time: “I want for nothing, and still I add / memory and desire to my cart.” As the poem ends, a different voice, perhaps closer to the poet’s own, emerges, as if from the heap of surveyed items, postures, and quips, to tell us what is most important:

You think

I’m grasping for answers

when really all I want is to lean

into language, and let go.

Banks’s intense relationship with language, then, might be his truest concern. And the middle section in Alternator, titled “Say Dynamite,” takes a playful turn, presenting longer poems that interweave idiomatic play with a similarly scaffolded “I”:

I need a tuning

fork for the real. A rain check for the miraculous.

Formally, this section resembles the work Banks presented in Midlife Action Figure (2019) and Deepfake Serenade (2021): declarative, without stanza breaks, the poems zing along in the superlative. The epigraph for Deepfake Serenade quoted the American poet Stephen Dobyns—“It is hard to mix emotion and sincerity with irony and distance.” This could well be a description of Banks’s writing in “Say Dynamite,” including the rueful “Ode to a Broken World”:

That prismatic

understanding. That inner drug. That symphonic

upwelling of Yes! We crave those moments while

rowing across the Lethe of another workweek,

another month, another year. Our sitting atop

mountains of plunder and thinking ourselves poor.

It’s in the third and final section of Alternator that Banks surprises his readers. Reflecting on his posture towards life, the poet identifies the wish behind his own vacillations—

This is not an urn of images, nor is it a proper self-depiction.

I couch-surfed for years between the ordinary and ecstatic,

between my head’s penthouse, my heart’s studio apartment,

waiting for the lived truth to unveil itself.

While the narrator insists the depiction of self here is not “proper,” it is novel—sits closer to the bone, scaffolds falling away. Why? Based on the final section, which meditates on sobriety, joy from a new romantic relationship, and other forms of “lived truth,” Banks’ life has simply changed.

The final poems present Banks’ new way forward, poetically and experientially. Slower, less productive, but sweeter, this path accepts life as it is—or tries to. From the twenty-second sonnet:

Why settle for the second-rate?

Because we can improve ourselves to the point of forgetting grief or

love, which is why I let the dishes pile in the sink and the chore list

sits undone, my mind revelling in life’s want, my eyes meeting your

eyes

In Alternator, Chis Banks may be unmaking his own writing machine. The collection proposes a modified form of address that bypasses the heady language of his oeuvre to date in the name of meeting his reader eye to eye.

*

Marguerite Pigeon writes poetry, fiction, and reviews. Her latest publication, a book-length poem called The Endless Garment (Wolsak & Wynn), was named to The Globe and Mail’s Top 100 books list for 2021. Originally from Northern Ontario, she lives in Vancouver, where she runs a small editing and writing business, Carrier Communications. [Editor’s note: Marguerite Pigeon’s The Endless Garment is reviewed here by Heidi Greco. Pigeon recently reviewed poetry by Nicholas Bradley, Cecily Nicholson and Arleen Paré in BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1966 The brutal stuff of life (with a side of contentment)”