1918 Seeing lives behind the art

Artists and Their Autobiographies from Today to the Renaissance and Back:

Symptoms of Sincerity

by Charles Reeve

New York: Routledge, 2023

$128.00 (USD) / 9780367221324

Reviewed by John O’Brian

*

In 1968, Andy Warhol was shot in his New York studio. Valerie Solanas fired twice from close range at his chest with a handgun, and Warhol was thought dead before doctors managed to revive him. More than four hundred years earlier, a goldsmith was killed in Rome by Benvenuto Cellini, a rival goldsmith. Unlike Warhol, this victim did not return from the dead and Cellini had to flee the city.

In 1968, Andy Warhol was shot in his New York studio. Valerie Solanas fired twice from close range at his chest with a handgun, and Warhol was thought dead before doctors managed to revive him. More than four hundred years earlier, a goldsmith was killed in Rome by Benvenuto Cellini, a rival goldsmith. Unlike Warhol, this victim did not return from the dead and Cellini had to flee the city.

Aside from murder and mayhem, what connects the two incidents? For a start, Cellini and Warhol write about them in their respective autobiographies, Vita and POPism. Written between 1558 and 1566, Vita is the first modern autobiography by an artist, a larger-than-life-tell-all narrative involving art, sexual intrigue, codes of honour, and homicide. POPism is cast in a comparably modern mold; it is the ultimate insider memoir on art, celebrity, and cultural revolution in the 1960s. The art historian Charles Reeve also writes about the incidents, linking together the autobiographies by Cellini and Warhol in his new book Artists and Their Autobiographies. Reeve’s fascinating study reimagines how we should think about the life writing of artists, exploring the genre’s “relation to fiction, serial autobiography, ‘as-told-to’ narrative and what happens when liars tell all.” Autobiography is closer to the novel, he argues, than to a factual document.

It may puzzle sceptics why artists, ardent investigators of the visual, have spent so much time over the past four hundred years engaged in the business of writing about themselves. Why fiddle with words when you are already fiddling with paint? Why put down a brush to pick up a pen?

Artists and Their Autobiographies comes at the question from several directions. The book is episodic in structure, moving backwards and forwards in time, mostly from present to past, with the chapter on Warhol coming at the beginning and the one on Cellini at the end. In between are chapters on Judy Chicago, Faith Ringgold, Saul Steinberg, Leonora Carrington, Mary Bashkirtseff and Mary Delany, to say nothing of sections on Elizabeth Murray, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun, Harriet Hosmer, William Hogarth, Elizabeth Butler and Tracey Emin. One of the achievements of the book is to recognize that autobiographers who are artists come in all shapes and sizes. Although rarely acknowledged in the literature, they cross racial, sexual and gender boundaries with abandon. The chapter and section headings alone are enough to convince me that a reconsideration of the genre is long overdue. Reeve is to be congratulated on mapping new terrain in his investigation.

The author is critically aware that memory and truth are slippery commodities. “Falsehood is a structuring principle of autobiography,” he declares, and shows why this is the case in one telling example after another. Like others engaged in life writing, artists misremember and fabricate, most of all when they are claiming to tell all (like Cellini and Warhol). This seems not to trouble readers. They are not looking for factual precision, Reeve concludes, as much as they are looking for convincing expressions of memory that provide insight into an artist’s personality.

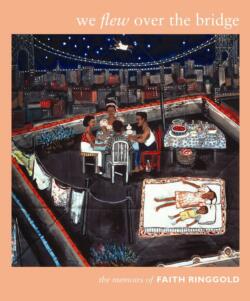

In her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, Faith Ringgold reports that she started out painting “trees and flowers in ‘French’ colors.” She also recalls that her New York dealer bluntly told her, “You cannot do this.” Ringgold took the statement to mean that as a black woman, born in Harlem in 1930, she could not hide behind flora and fauna at a time of social upheaval. She needed to address her moment in time, whether directly on indirectly. Instead of dealing with trauma, she decided to engage in “magical thinking.” She writes in her autobiography: “I don’t want the story of my life [and art] to be about racism, though it certainly played a major role. I want my story to be about attainment, love of family, helping others, courage, values, dreams coming true.” The truth she wants to impart is about hope.

In rethinking the genre of autobiography written by artists, Reeve is conscious of his own place in the narrative. He often inserts himself and his friends and associates into his story. “Tall, garrulous and relentlessly good-humoured,” Artists and Their Autobiographies begins, “my late friend Robert Linsley was one of those artists whose inventiveness flows from energetic, wide-ranging curiosity.” Reeve claims that Linsley’s reading recommendations for him, beginning with Cellini’s Vita, are the impetus for the book. There is no reason to disbelieve him, except that after reading the volume backwards and forwards I would be doing it a disservice if I took the claim entirely at face value.

In the interest of transparency, it needs to be disclosed that I make a cameo appearance in the book. Reeve states that I taught a course at the University of British Columbia, where he completed his BA and MA in art history, called “From Morelli’s Ear to Guilbaut’s Raised Eyebrow.” The title is a play on the turn in the discipline from connoisseurship studies to social art history. But I have no recollection of teaching the course. Has memory failed me, or is Reeve perhaps mistaken? In the realm of autobiography, it does not much matter. Readers will embrace either version of the event, as long as it strikes them as revealing and sincere.

*

John O’Brian’s latest books are The Bomb in the Wilderness: Photography and the Nuclear Era in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2020) and, co-edited with Claudette Lauzon, Through Post-Atomic Eyes (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020).

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster