1790 Thom’s modernist masterpieces

Ron Thom, Architect: The Life of a Creative Modernist

by Adele Weder

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2022

$37.95 / 9781771643221

Reviewed by Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe

*

Ron Thom, reflecting in the early 1980s on his work as a creator of living and lived-in spaces averred, “any form of design or expression is locked in time. Whether it wants to be or not, it has no choice but to reflect and in a sense become a product of the thoughts and attitudes that surround it when it is being formed.” This quotation comes from the hand-written text of a lecture conserved in that excellent resource for the study of modern Canadian architectural enterprise, the Canadian Architectural Archive at the University of Calgary. Those sentences relate indirectly to the astute and vivid recovery of the life and times of this remarkably talented if troubled architect achieved by Adele Weder.

Ron Thom, reflecting in the early 1980s on his work as a creator of living and lived-in spaces averred, “any form of design or expression is locked in time. Whether it wants to be or not, it has no choice but to reflect and in a sense become a product of the thoughts and attitudes that surround it when it is being formed.” This quotation comes from the hand-written text of a lecture conserved in that excellent resource for the study of modern Canadian architectural enterprise, the Canadian Architectural Archive at the University of Calgary. Those sentences relate indirectly to the astute and vivid recovery of the life and times of this remarkably talented if troubled architect achieved by Adele Weder.

Through extensive archival research, but perhaps more importantly, interviews and on-site visits, Weder has illuminated what might be termed the time of meaning in Thom’s architecture. She has captured the imprint of chronological and cultural condition — inevitably embracing political and economic as well as personal factors. In tandem she has articulated the new meaning that an individual can impress upon the societal fabric at a particular juncture. As she demonstrates, Thom actively embraced the opportunities opened up in architectural practice, and in his native western Canada, after the end of the Second World War. Those can be simplified as concepts of built-form freed of academic lore but driven by a design strategy that focussed on efficiency and economy of function and structure. A strategy that was wedded to transparency and lightness, combined with a broadening democratization of the social order. And one enabled by the availability of inexpensive real estate plus new techniques such as kiln-dried wood post & beam structure, plywood or large-scale glazing.

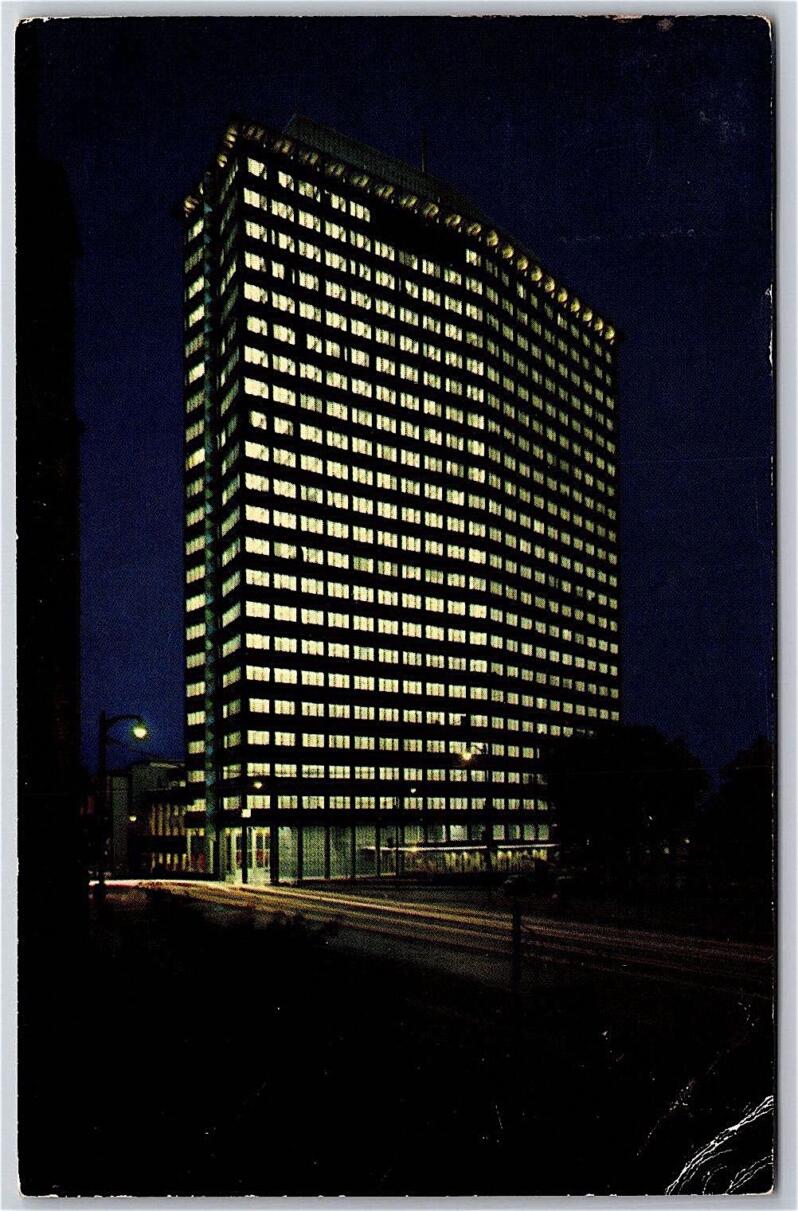

In the wider temporal perspective delineated by Weder, Thom’s career spanned the tremendous optimism accorded design in the late 1940s into the mid-1960s and its demise from the mid-1980s. He entered the profession when architecture seemed to offer the potential of re-engineering society. An objective to be attained through private and public commissions, together married with comprehensive town planning — signified by the establishment of Central [Canada] Mortgage and Housing Corporation in 1947 and legislation consequent upon the Massey-Levesque report on the National Development of the Arts, Letters and Sciences completed in 1951. Thom’s career collapsed with the ascendancy of corporate-driven property development, neo-liberal dissolution of communal ethos and the general sidelining of architect initiative; either through the impact of fame culture, as reflected in the moniker ‘Starchitect’ or the elevation of developer promotion over architect authority the phenomenon defined by this reviewer as ‘Archi-tizing’ (in Architecture and the Canadian Fabric, UBC Press 2011, pp. 409-25). Even back in 1960 the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada commissioned Thom’s erstwhile champion Ned Pratt — vide their noteworthy collaboration on the construction of that notable Vancouver modernist edifice, the B.C. Electric Building — to compile a report diagnosing the diminution of architectural activity in the build out of Canada.

A coda bears inserting here about both that historical era and Weder’s writing of his [Thom’s] story. She adeptly accounts for an often-overlooked aspect of the Modern Movement, namely the appreciation of historical design solution. John Bland at McGill and his Toronto University colleague Eric Arthur not only published books on traditional regional construction but also encouraged their students to learn design thinking through investigation of such past practice. Indeed, the British architect Ralph Tubbs was not alone in regarding the rational classical fundament of Georgian-Regency design as a direct antecedent of Modernist praxis; recall, too, Mies van der Rohe’s modern neo-classical early villas.

Similarly, Weder tells of Thom’s insightful perambulation of Oxbridge colleges in figuring and then executing a true masterpiece of Canadian architecture, Massey College. In the lecture quoted at the outset of this review, Thom noted the significance of “developing tradition [in architectural design] — the using of things which have developed by trial and errors and correction over time.” And he added two further sentences which illuminate the extraordinary distinction of his architecture, declaring that “Designs should not be pre-occupied with self-identification — the subject, or the object designed should be all — its raison d’etre — free of the designer’s trademark.”

That insightful comment is paralleled in the approach to architectural history pursued by Weder. She neatly manages the anecdotal dimension that is essential to fuller critical analysis of event and product — and in this instance to design process. As part of defining his work, she addresses matters of personal capacity and interaction. With respect to the former, she acknowledges Thom’s intuition: his empathetic response to site, client preference, appropriate formal symbolism, and his privileging of artistic endeavour. Her relating of the anecdotal spaces of lived experience affords a valuable window on Canadian architectural culture in Thom’s lifetime.

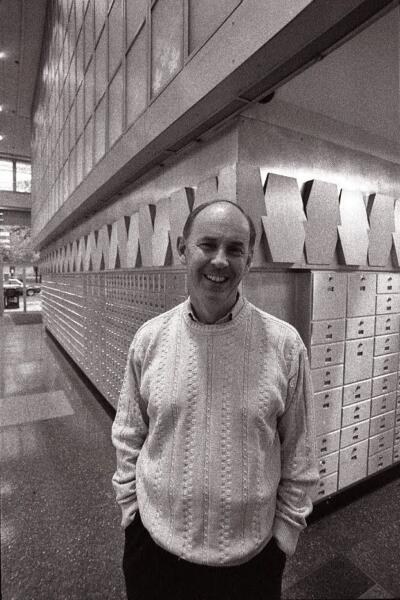

Those spaces range from the personal to the professional. One example is mention of the boredom and drinking attendant upon his wartime service in the RCAF that eventuated in his tragic alcoholism. Another is his desire to fly, perhaps as a means further to comprehend the nature of space; interestingly his early co-designer Fred Hollingsworth became an accomplished pilot. Weder sympathetically recounts Thom’s failure to obtain a pilot’s licence and the withering effect upon his marriages and practice of the demon drink, an addiction which precipitated expulsion in 1986 from the offices of his Toronto firm, R.J. Thom and Associates. More valuable for Canadian architectural history is her lively reconstruction of the daily round in the architectural offices and designer complement of his workplaces at Vancouver and Toronto. Thereby, she ably enlarges the extant literature of Canadian modern architecture across Canada (comprehensively cited in her bibliography and endnotes).

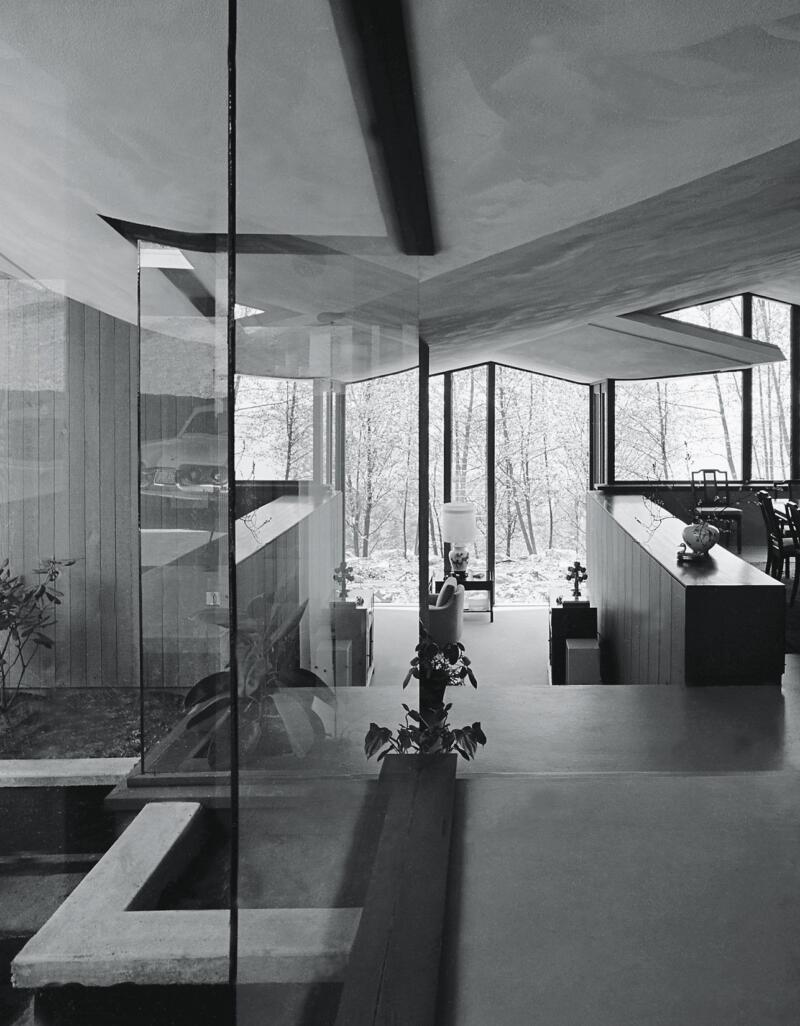

Weder deserves an additional encomium. Her articulation of design performance alongside designer persona adds lustre to the prior monograph on Thom, published by Doug Shadbolt in 1995. Her descriptions of such domestic design as the Forrest, Case and Narod houses or institutional buildings such as Trent University, capture architectural intent as well as effect, and, perhaps more commendably, affect. That latter quality encompasses the visual and psychological character of singular or communal space as well as the impact of buildings on the environment.

A Parthian arrow: the text is eminently readable and culminates with the funeral oration spoken by Barbara Frum, a person who relished living in one of the many living spaces Thom had imagined and realized. However, looking today toward Point Atkinson where his family cast Thom’s mortal ashes, perhaps the most telling epitaph belongs with another talented architect, his friend and sometime partner in form-making, Paul Merrick, “By god that bugger really did know how to design a space.”

*

Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe headed the Department of Fine Arts (now Art History Visual Art and Theory) at UBC and the Individual Interdisciplinary Programme before serving as Associate Dean of Graduate Studies at UBC. A Guggenheim Fellow and recipient of the Margot Fulton Award, his many publications on architectural history include Francis Rattenbury and British Columbia: Architecture and Challenge in the Imperial Age (UBC Press, 1983, with Anthony Barrett); The New Spirit: Modern Architecture in Vancouver, 1938-1963 (Douglas & McIntyre, 1996); Architecture and the Canadian Fabric (UBC Press, 2011); and Canada: Modern Architectures in History (Reaktion Books, 2016, with Michelangelo Sabatino), reviewed here by Martin Segger. As Rhodri Jones he has written a memoir, Edges of Empire: A Documentary (Rarebit Press, 2017). Editor’s note: Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe has also reviewed a book by Matthew Soules & Michael Perlmutter for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1790 Thom’s modernist masterpieces”

The Canadian Architectural Archive at the University of Calgary, eh? That sounds like a truly valuable resource! It’s so important to preserve and study our architectural history and see how it’s shaped our communities. I’ll bet there are some fascinating drawings and documents in there. It’s great to know that such an archive exists to help us understand our built heritage.”

I went to visit at Ron Thom house in Surrey today, it is up for sale on 1 acre of land on the bluff – it was built for husband and wife Narod in 1969. Apparently the only house built this side of the Fraser by Thom. You may want to have a look at it – as it will most likely be torn down. I took some pictures and videos if you are interested in seeing them. A shame! Super cool place!