1788 Chinese daughters and mothers

Superfan: How Pop Culture Broke My Heart. A Memoir

by Jen Sookfong Lee

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (McClelland & Stewart), 2023

$24.96 / 9780771025211

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

A rather unfortunate acquaintance of mine suffers, periodically, from foot in mouth disease. It’s not her fault — but it’s not not her fault, either — and maybe she’s spent too much time on certain Reddit threads; I can’t say for certain.

A rather unfortunate acquaintance of mine suffers, periodically, from foot in mouth disease. It’s not her fault — but it’s not not her fault, either — and maybe she’s spent too much time on certain Reddit threads; I can’t say for certain.

Though she has a warm demeanour and appears well-intentioned, she has, on more than one occasion, intimated that she is tired of identity-driven writing. In other words, she is tired of reading about race. Whether, of course, anyone is tired of having to write about race, is not something she has considered. “Why does everything have to be about race?” she says, legitimately baffled by contemporary fiction with the gall to acknowledge that race, sociologically speaking, exists in ways that affect lives. She continues, and I paraphrase: “I want to read about mothers, mechanics, and monkeys … ” Apparently none of those roles, unlike race, are considered identities.

Yes, the acquaintance is a white woman, but let’s not oversimplify here. Let’s unpack how this woman believes race = identity, but motherhood (she is a mother) isn’t. Could it be that when, other people, with wildly different life experiences she cannot relate to, simply overwhelm with the weight of their identities, in every sense of the word — so disparate from hers — and thus become, to her, an amorphous puddle of Identity Whinging I Don’t Even Want to Understand? From her perspective, if someone writes about motherhood, that’s not identity-specific, per se, but rather, a broad cultural phenomenon that white women like herself can partake in, a veritable buffet of potential feminism.

I can’t pretend I understand this acquaintance’s mindset. What I do know, though, is that she is deluded. Identity is not some monolithic rhombus; identity is more like a mosaic of intersections abutting and clashing and colliding and forming reverse y axes that make you wonder why economics had to have its own set of rules for graphs; it’s where your parents came from, whether you are a parent; where you were born; whether you can snap your fingers; whether you like to bite gummy bear heads off; it’s skydiving; it’s jewellery; it’s antidepressants; it’s your oral microbiome; your gut microflora; it is all of these things, and so much more.

And so, when I was asked to review Superfan, an essay collection by Jen Sookfong Lee, I could not help but think of how this acquaintance would probably balk at how unapologetically and wonderfully identity-driven Superfan is. On the other hand, though, perhaps this woman would read Superfan and, best case scenario, realize her patterns of thought were not as judiciously linear as she may believe; she might come to realize other identities matter — once she’s made peace with them existing — and realize: they can be exceedingly well-written. At its most realistic, reading helps you pass the time and you get to feel like you have an intellectual hobby. At best, reading leaves you awe-stricken with the beauty of its syntax and you become the sort of dreadful person that says on a sentence level.

On a sentence level, Superfan glides. It was difficult to stop reading. And, on a content level, it was also difficult to stop reading. I consumed Superfan like cotton candy, except instead of dissolving, I was left with an uncomfortable recognition.

Did I, as a conspicuously Chinese Canadian, relate to Superfan? I did, but again, I don’t want to oversimplify. When I say I related to the book, I mean that the essence behind certain challenging feelings gave me resonance, pause, and an odd gratitude that someone else has successfully vocalized familiar feelings. I don’t mean to say that the Chinese Canadian, or otherwise racialized, female-appearing experience is a homogenous misery that can be understood by outsiders if one simply reads enough books written by people of colour, though, that’s a start. It is disturbingly easy to shovel racialized people into a heuristic and go, Ah yes, that is what it’s like to be them.

Lee’s essays mention several figures that are pleasingly and/or wretchedly familiar to me, from Anne of Green Gables, to the Kardashians, to Ali Wong, to Joy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. She talks about interracial relationships with white men who end up with white women; she talks about being mistaken for other Asian women writers; she talks about divorce; being a daughter; and being a mother. For those partial to Whitman paraphrasing: everyone contains multitudes. (If this review sounds more like a PSA than a review, let’s just say I’ve met too many people like the aforementioned acquaintance with foot in mouth disease).

East Asians have long been making themselves palatable — to be accepted, to get ahead, to have getting ahead be the way towards acceptance. Sometimes that effort towards palatability, which often means self-erasure, is deleterious. Sometimes being who you are, whatever that might mean, gets considered by another Asian person, as erasure (ask any Asian woman who has ever dyed her hair blonde). Nobody judges an Asian person like another Asian. Cumulatively, all this crap has the possibility of making an Asian person feel like there’s a quota on how many misbehaving, vulgar Asian women there can be. Well, here goes: there’s no quota.

There is nothing mere, or inconsequential, about pop culture. Of course, it must be acknowledged that pop culture — right down to the pop in its name — promises a sort of frivolous escapism, the lure of pleasingly detailed, feminized vacuousness, followed up with something resembling guilt for not having single-handedly ended Internet addiction or global rising temperatures. But in the same way that a lover’s taste in pornography may provide horror, insight, and pause — not necessarily in that order — doesn’t a person’s participation in pop culture ultimately reveal something about themselves?

There are more important things than who is dating whom or who wore what dress. And yet, the way we talk about celebrities, particularly, female-appearing celebrities, provides an excellent lens on how society, generally, feels about women (spoilers: it’s not great). It’s where the real, unpasteurized, judgemental thoughts come out. It’s where, with a hopefulness we might not even recognize, we wonder if we might see someone, being awesome and looking awesome, who kind of maybe looks like us, somehow. On a soul level, even.

And so, when Lee talks about how friends compared her to the comedian Ali Wong, I felt a keen sense of recognition. If Ali Wong was Alice Johnson and telling the same jokes — though, of course, if she were Alice Johnson, she wouldn’t be telling the same jokes — it’s doubtful that anyone would think to compare Lee to her. But because Alice Johnson is Ali Wong, and because Ali Wong is crass, uproariously funny, and bespectacled, the comparisons between any remotely “misbehaving” Asian woman are, perhaps, irresistible. After all, how many crass, funny, flamboyantly bespectacled Asian women in leopard print dresses in Hollywood can you name? Or even just: how many crass and funny Asian women in Hollywood can you name? Go ahead. I’ll wait.

(If you came up with Sandra Oh’s character, Cristina Yang, from Grey’s Anatomy, I understand. And if you came up with nothing, I also understand. If you’ve never seen it before, your modes of comparison are limited. If you want to see awkwardness, watch the disgraced but not permanently disgraced Alison Roman trying to name five Asian women — not necessarily celebrities, just any five Asian women — by Ziwe Fumodoh). So: expand the visual horizon. Let an Asian woman who dares to swear become as unremarkable as wallpaper, or a white woman.)

Lee writes:

With her big glasses and loudly patterned dresses, she looked more like me than any other famous Asian woman I had ever seen. My friends would say, “Have you watched Baby Cobra yet? She is just like you.” I shrugged. I was used to being compared to other Asian women in the media, even if we were nothing alike. Newscasters, singers, the doctor who dispensed advice on her own cable television show. Sure, sure, they were all just like me.

… Wong made jokes about her sexual past, about the condition of her pussy, about insulting Korean people when she and her husband are alone. Was the bearded man she slept with in her single days homeless or just a hipster? Is an HPV infection a badge of honour? Is it true that opinionated Asian women who wear big glasses only sleep with white men? (Spoiler: yes.)

I laughed. Hard.

Visual representation is one thing, a very important thing. But so is a representation of sensibility, of the thoughts you mull over but never speak, of the desires you’ve kept hidden, of the jokes you’ve only made with your closest friends over wine, in the safety of your kitchen.

We had seen so much Asian female pain. Ali Wong brought us Asian female joy.

Here was the joy and raunchiness of my innermost self being spoken by someone I’d never met but who made me feel like I was looking in a mirror. … Watching Ali Wong say what I had only kept inside made me realize I too could want things, I could be angry, I could be funny, I could be dirty. Readers seeking stories of subdued intergenerational conflict might hate that. Book prize juries looking for trauma narratives focused on the pain of immigration might hate that too. My mother for sure would hate that. But fuck them. Fuck them all.

Indeed.

When my mother saw Ali Wong’s memoir, Dear Girls, on the coffee table, her first response was: “That was written by an Asian person.” There was incredulity. Incidentally, my mother has the same reaction to every book where the author is an Asian woman. Maybe I should send her Superfan.

I think my mother’s soul, or at least, part of it, left her body when she realized how unfit I am for basically most kinds of work, let alone an air-conditioned office job where my biggest problem would be ascertaining the true meaning of business casual and how to pretend three hours of work could take up eight. And yet, when my mother sees a book written by an Asian woman — for some reason, most books written by Asian women have an Asian woman’s face on it, in case the last name isn’t a big enough signal — there’s something resembling hope on her face. Something. There’s a shock that teems with reality — here is this unlikely thing in corporeal form, something that, however vestigially, signals that the somewhat asinine literary dreams I have for myself, might not actually be impossible.

I, too, have been compared to Ali Wong — and it is always a compliment, though perhaps a bit of an insult to Ali Wong – while, interestingly enough, no Asian person has ever compared me to Ali Wong. Leave it to an Asian person to tell the rest of us apart, if no one else can, something Lee mentions when she is in conversation with Evelyn Lau and Fiona Tinwei Lam:

I said, “If I had a dollar for every time someone called me Evelyn,” and all three of us laughed. But the laughter was suffused with rage, with the knowledge that reading our books makes white readers feel better about themselves and their commitment to diversity, even if, most of the time, they still can’t tell us apart.

Fiona said, “Let’s take a picture. To prove we’re not all the same person.”

… Three hours later, I went home with a white man who unbuckled my shoes and held me as I slept, and I tried to believe it was love. He left at seven in the morning, and when I looked at my phone in the ensuing silence, I saw that photo of our three beautiful Chinese faces, the red light like a cloud of fire — or love — behind us.

Lee knows when to give the reader space when she opts for starkness and concision. For instance, when she writes in list form:

Things my mother said to me after my divorce:

“No one else will ever want you now.”

“You are ruining my grandson.”

“You were always the uncontrollable one.”

“Your ex-husband’s new wife is very pretty. I can see why he chose her over you.”

“Stepfathers will molest your child.”

“I am so ashamed.”

There is no self-pitying dwelling; her mother’s words are quite enough.

And this line: “I had to ask to learn the oboe, but my mother shook her head and said, “Girls should never put objects in their mouths.” There is no further elaboration.

Out of context — all these admittedly terrible opinions presented as facts, as only a mother can venomously utter — are translated (Lee’s mother does not speak fluent English). They are the kind of things you can produce on demand if you happen to have an audience craving Mean Asian Mother stories. Fun fact: if you try to tell a Mean Asian Mother story to another Asian person, though, it might become a competition of one-upping. Or it may come down to something as simple as what Hoa Nguyen said to Cathy Park Hong: “You have an Asian mother. She has to be interesting.” I can hardly disagree, though I cannot help but think of an elementary school teacher of mine suggesting that, whenever we had nothing nice to say, we could say it was interesting and henceforth, every baby I have ever seen has been interesting.

Park Hong declined to speak about her mother, understandably, but Nguyen, of course, is absolutely correct. If two Asians talking about their respective mothers doesn’t become a competition, it might just become a sequence of laughter where crying would actually be more appropriate.

But a good parallel to Lee’s mother’s upsetting pronouncements comes, perhaps improbably, from a scene in Mad Men, where Joan, an office manager renowned both for her fierce competence and attractiveness, condescendingly tries to give fatphobic — though it would not be recognized as such, back then — advice to Peggy, a former secretary recently turned copywriter. Peggy, no longer the acquiescing doormat she was in the pilot episode, sizes up Joan, accurately:

“You’re not a stick.”

“And yet I never wonder what men think of me. You are hiding a very attractive young woman with too much lunch.”

“I know what men think of you: that you’re looking for a husband, and you’re fun. And not in that order.”

“Peggy, this isn’t China. There’s no money in virginity.”

“I’m not a virgin.”

“No, of course not.”

“I just realized something. You think you’re trying to be helpful.”

Admittedly, it defies logic to try and explain how a mother telling her divorced daughter that the ex-husband’s new wife is prettier than the divorced daughter, could be helpful, even in the manner of Joan. (After all, doesn’t that also insult the mother herself?)

But if we can go beyond the obvious, possibly calculated cruelty, there’s something else there: an idealism that has been shattered. Joan assumes, incorrectly, that Peggy wants what Joan wants, which is what Joan has been taught to want: a husband. There are relatively straightforward ways to acquire said husband. (To quote Cassie from Promising Young Woman: “If I wanted a boyfriend, and a yoga class, and a house, and kids, and a job my mom could brag about, I’d have done it. It would take me 10 minutes. I don’t want it.”)

Lee having once been married, is probably as close as Lee came to fulfilling an unimaginative, societal ideal. And that got shattered. The catastrophizing that Lee’s mother does is dreadfully familiar to me.

Lee writes that:

Respectability for Chinese women is a complicated knot, one that has its origins in history, in Confucianism, in migration, in popular culture. My sisters and I, and many Chinese women who grew up in North America, were raised to believe that there is one way to stay safe, and that is to be good. If you’re nice and polite, the next time a drunk man in a bar hisses that he saw a girl just like you on Pornhub, another man will step in and push him away. If you’re pretty but not too sexy, the police officer will wave your car through a check stop, even if you’ve had a few cocktails. If you have good grades, no one will ever suspect your boyfriend is a gangster.

But if you’re bad, there are no guarantees. Your family could disown you. A white man could rape you and no one would believe you. You might never graduate from high school and have to work in a nail salon in a strip mall, scraping the feet of women who think they’re better than you. You will bring shame to your parents. This, by far, is the worst of all outcomes.

I used to go to the movie theatre, alone. Sometimes these movie screenings were in the evening. Before I left the house, without fail, my mother would tell me that I shouldn’t be going out, because if something happened to me — namely, rape — it would be my fault. (Victim blaming is not in mother’s vernacular). According to my mother, the newspaper headlines would say I had been out late at night, which reflected poorly on me as a victim; indeed, it made me more culprit than victim. Sometimes she would go into detail how my theoretical rape would be deeply unpleasant — the rapist would confiscate my glasses and I would be unable to see my rapist clearly, and therefore unable to provide a detailed report that would assist police officers in catching the rapist. I wasn’t sure why, in these warnings, my mother thought the police would be helpful, but that’s misplaced, shortsighted idealism at its maternal finest for you.

I will say this for my mother: she did not actually interfere with me leaving the house to attend to generally wholesome activities; she just ensured that I had rape on my mind every time I left the house. (In any case, perhaps even without her interference, it would still be on my mind, even though most of us know by now that women are, more often than not, raped by someone they know, not a stranger. Trust, possibly, even).

And yes, my mother thought she was helping me. Just like Joan. And just like Lee’s mother.

The end of Lee’s essay collection neither ends with a bang, nor a whimper; there is a self-referential thing that simultaneously seems to reference a troubled past, and a glimmer of hope for a new narrative:

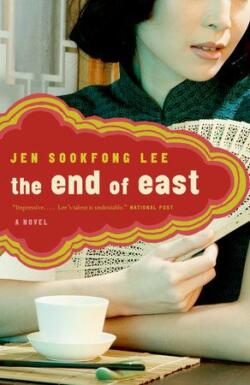

The cover of my first novel features a Chinese woman in profile, sitting with a cup of tea. When I first handed my mother her copy, she held it in her hands, turned it over, running her fingers over the smooth coated paper. She didn’t need to be able to read English to know that the book was very Chinese. She gazed at my author photo on the back. She nodded, as if to say, Yes, that’s my girl.

“What do you write?” she asked me. “What is in the book?”

“Stories,” I said. “About Chinatown. About families.”

Her face lit up. “About me?”

“Not really. There is a mother in my stories though.”

“Oh.” The disappointment seemed to wash over her and she sighed. “I hope you are kind to her.”

If you’re looking for “Longevity noodles. Long beans. Prosperous whole steamed fish,” then look elsewhere, but if you want candid, nuanced writing with ferocity and canny pop culture references, read this book.

*

Originally from East Vancouver, Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and a pianist of dubious merit living in Toronto. She is currently an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has recently reviewed books by J.M. Miro (Steven Price), Bri Beaudoin, Tetsuro Shigematsu, Katie Welch, Megan Gail Coles, and Ayesha Chaudhry.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1788 Chinese daughters and mothers”

Loved this review of Jen Sookfong Lee.