1745 Built on a Dream

Built on a Dream

An audio piece by Anne Watson

*

Introduction. Built on a Dream includes the voices of a narrator, a storyteller, and a historian. Positionality and self-conscious awareness matter in this experimental piece. I’ve written it different ways over the years: this is my first attempt using multiple voices. Pierre Bourdieu’s “Biographical Illusion” helped me think about how to tell this story, particularly his writing about the intersection of the narrator or interviewer vis-à-vis story and characters. The narrator, as an interviewer, occupies a specific space, ordinarily one of power, in relation to a biography. Yet in this telling, the character of the house assumes the role of storyteller, thus once removing the narrator from the subject even though the house is a construct of the narrator’s memory and dream. Memory and dream function as mechanisms meant to break assumptions of chronological structure and assumed truths, and signal that the characters are fabricated. Perhaps this is my way of positioning at a distance, in the sphere of imagining instead of knowing, since I feel, at least sometimes, a trespasser writing what Hermione Lee refers to as “hidden history” and in this case, one which is not mine. Lee writes that hidden histories are “a changing genre, not a fixed entity,” and I can’t help but wonder if the very way we think about history and race isn’t itself always in flux.

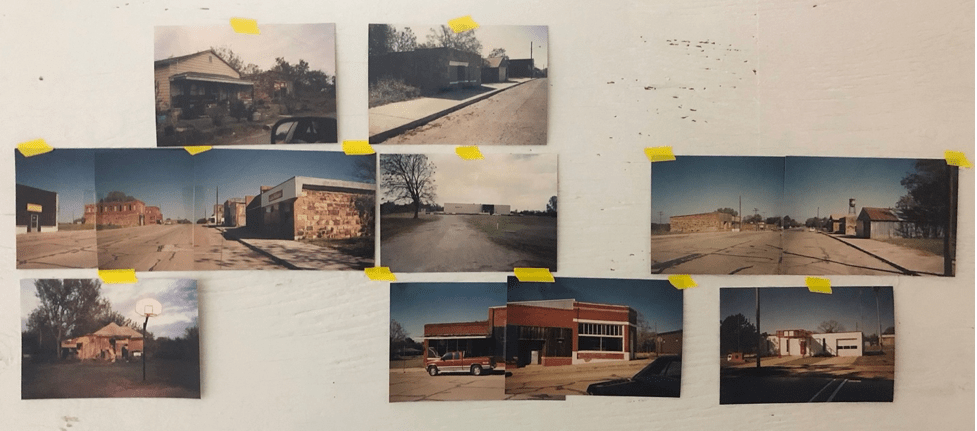

I decided to tell this story because I am personally attached to it, share an intersecting history with it, and consider it American history in the truest sense. I met inhabitants from all-black towns in the late 1990s, and I’ve carried their photos in a box and their stories in my memory. I’ve also carried a feeling of unfulfilled responsibility to those who generously shared their life stories with me.

My intention was to create a dialogic positionality. I sent the written piece to Quintard Taylor, the foremost scholar of African American history in the western United States and a consultant on one of my past projects, and asked if he would respond. I wanted whatever thoughts he had – explanations of why I shouldn’t be writing this as welcome as anything else. My idea was that his responses would provide balance, and together with my writing, present a third way of understanding this history/biography. But he never responded.

So, I talked to other people of colour who I thought might help position the piece. Wayde Compton, a writer and professor, thought the dialogic interplay of voices and varying views would provide the positionality needed but without that dialogue I would have to be very clear about why I chose to write this story; Soheila Esfahani, a professor at Western University, told me I shouldn’t have asked Taylor to respond, that I was asking a marginalized person to provide validation for my piece; and Jessica Karuhanga, an artist and professor who grew up in the US, thought it an interesting and important endeavour. Each response reflects an individual perspective, based on personal experiences 00 one person navigates through life with mixed-race identity; one, lives as a Muslim immigrant; and the third, is an African Canadian who understands the power dynamics of race, gender, and status in the US.

For me, this is as much what this piece is about as the telling of a story — Anne Watson

*

Audio piece: The three readers of in this version are: Anne Cullimore Decker, the house; Don Shafer, the historian; and me, the narrator. Earle Peach recorded and performed the music. It’s important to note that we are all white.

Audio Player

*

House: If you come near, I’ll tell you a story.

Narrator: Her voice, faint and distant, enters the car through the open window.

She barely holds herself together, like a hurricane ran through her, rattling her bones, stripping her of clothes, burying her shoes deep in the ground several plots away. What’s left of her body is brown and black; her skin, aged, wrinkled and splintered. Large holes open in her side; prairie grass and trees grow through her. The land offers no mercy, neither embracing nor cradling but instead spreading out flat and dry and hard, the horizon eternally distant, the sky ominously broad. On extremely rare rain days, clouds in perpetual variation and motion streak the sky counties and miles away in one direction and allow slivers of sunshine in the other.

It’s overcast here in the town of Ezana. A soft blanket of light saturates scattered spots – a couple sunflowers intensely orange, spiderwort shining like amethyst, a few blades of grass, peridot, an old, twisted Coke can, glowing strikingly red.

I park, get out of the car. The air is parched like my white skin that won’t rub off. My body is sticky from the heat, my lungs stiff from the dust. I’m only a traveller passing through, but I’ve been here before. At the time of the O.J. Simpson trial, I drove across the tabletop flatness of Oklahoma and Kansas from one all-Black town to another, meeting many people as a researcher trying to piece together ignored history. No one I met was younger than 72 years old. They are ghosts now. Their small frame houses in — Clearview, Boley, Nicodemus, and Ezana — were falling apart back then. But in my mind, they stayed together, settling into a mental landscape like colonizers, their presence reverberating in an echo chamber where hot breezes pass endlessly through fallen roofs, sparrows nest in broken eves, grey squirrels scamper through split, disintegrating timbers. These vanishing homes in all-Black towns became part of an artificial village, taking up residence and cohabiting through some odd neural phenomenon with Southern shanties, small houses of minimum wage workers, cargo containers for the houseless.

Narrator/Historian/House: This is only a dream.

House: I woke from the earth to the touch of hands — 20 hands, ten people, women, men, and children. From soil and prairie grass they moulded me, their skin calloused, their grasps strong, sweaty, and confident. Pushing, patting, and forming to make my body, they gave me structure, two windows and a door. The first sounds I heard were their voices, birds, crickets, and the wind. I could have survived just as I was, a sod dwelling – there’s so little rain — but when some money arrived, wood was purchased, and I was reconstructed with a frame.

I come from the earth, I know that. And it’s to the earth I will return. In the end, I will be a memory, a shell collapsed, and nothing will have depended upon me to survive.

Narrator: Her voice carries a weariness that seems to come from her bones. Renowned scholar of African American history, can you tell me why? Why are we so tired? Did it begin with the first Europeans, or start before that?

I wait for a reply.

There’s no response.

I walk toward her. A rusted truck is parked about half a mile off under a lone tree. A squirrel emerges from the dead engine and runs into a parched field. A screen door shuts in the distance. The clouds are rapidly clearing.

Where are you, scholar? Are you also weary? Tired of my questions?

Historian: History is complicated. There are many points of view.

Narrator: There you are.

Historian: For example, at the time of the Revolutionary War, the Delaware signed a treaty with the colonial Americans. It was beneficial to both signatories: the Delaware strengthened their position in their new lands; the Americans gained the Delaware as allies to defeat the British. But the fate of local Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kansa, Kiowa, Osage, Pawnee, and Wichita people was influenced as well, and without their participation.[1]

Also, impacted was the fate of fugitive slaves. In the fourth article of the treaty, the Delaware agreed to arrest and extradite “criminal fugitives, servants, or slaves.”[2]

MUSIC: Home on the Range, instrumental only

House: I’m tired.

Narrator: I pass an anemic row of once flowering plants to meet her behind a broken window. We are unprotected by walls though her heart still holds a stone fireplace; and her belly, a wood-burning stove kept as a memento. The stove smells of sweet squash. The shell of two small bedrooms complete her.

Historian: Ezana was founded over twenty years after the Civil War ended and four million slaves were freed. For a sweet minute, African Americans from the South believed there was hope of independent prosperity in lands west of the Mississippi, in Kansas and Oklahoma. Those who were self-determined took advantage of the Homestead Act or purchased plots of land from promoters: they were “..actively searching for promised lands…(that could offer) the greatest potential for their dreams of freedom to be actualized.”[3]

Narrator: I am dreaming, reconstructing a house.

House: The land where I live was purchased for $5. My family, like the other first settlers, came from Kentucky. The new migrants arrived on horseback, in stagecoaches, on foot, dragging small amounts of luggage, wearing worn clothes — over 300 of them, though many left after setting foot on the hard, inhospitable land.

Those who stayed worked hard, sustained by an abundance of hope. I was always freshly painted, immaculately clean, furniture adorned with hand crocheted doilies and needlepoint pillows. I even had an oil painting of a cross made of red roses placed on my hearth.

Three generations of a family breathed life into my lungs, and in return, I held them in my embrace, near my heart, loving them as they loved me. The children tickled my floorboards with their toes, brightened my walls with their laughter. Even though at times I felt like I was only a corridor to the street where the children played games and met others on their way to school. My belly heated the winter rooms with smells of soups, corn bread, an occasional turkey, and simmering greens. Cards were played, jokes told, arguments had, growing up done. The neighbours gathered around the upright piano and sang hymns some evenings and Sundays. When the community got the first gramophone, it came to me, its rollicking sounds rocking my walls.

I can hear their voices still. The slim, tall, educated town founder spoke softly, his voice quivering with pain, when recalling life in the South…“White devils killed my brother. God will punish them. There will be no mercy for their souls.” And then his voice quickened with decisiveness, “We will build here, make this home … a thriving community with doctors, lawyers, journalists, and educators. We’ll teach our children in all areas of knowledge…and again live independently. In this land of John Brown and abolitionists, we are finally free.”

Narrator: I sit on a weathered plank; it was once her polished floor. A Black Walnut branch falls to the ground beside me. A small sparrow appears/disappears, carrying a string of white worsted in her beak. Perhaps she is wondering why I am close to her nest.

House: Of those who lived with me, my favourite was Emerald. She was only four when her family arrived, and she stood out. Thin and pretty, her hair neatly plaited, self-contained to the point of being diminutive, she was silent and uncrying. Her brother was her opposite; he danced boisterously around his baby sister singing, playfully poking and teasing, making her laugh. But he couldn’t make her talk, no one could. She never talked to anyone…except her mama.

“I love you to the moon and back a million times,” she’d say, her child’s voice sweet and high, as she crawled into her mama’s lap on the small bed covered with a quilt patched in squares of history. She pulled her small legs to her chest, and pressed her head against her mama’s heart.

She grew tall and narrow bodied, her cheekbones high, her eyes bold black, her hair falling in long ringlets, but she hid this beauty inside her shoulders, like a broken princess, stooped by a weight others knew as well. Her curls masked what I thought was her best feature — huge ears, like elephant ears, which may have grown large so she could hear what others could not.

Many nights, she curled into herself on the old quilt, her mama sitting nearby, and explained the pain of being locked in her prison of silence. Her mother would reach over to caress her cheeks, the back of her ears, her bent neck. When Emerald lifted her face, her eyes seemed to look in and out at the same time, with sadness but also with light. The thing about Emerald was that she shone. Her smile, her laughter could turn the wind, wakening the leaves and branches and birds. She was magical…and strange, but never was she treated as an outsider. There were no outcasts in Ezana.

MUSIC: Home on the Range, instrumental only

House: By the time she was six, Emerald knew I listened along with her, and sitting cross-legged on her bed, she would lean her warm body into my wooden strength. Together, we heard everything.

One warm summer evening, the town founders and stakeholders, about fifteen of them, gathered. A tall, slim man brought news: ‘The promoters are talking of tens of thousands who could pour into Kansas from the South, a second, larger wave,’ he said. ‘The question is should they come here? Should Ezana be one of the towns advertised as a destination?’ The townspeople discussed through the night, some leaned on the hearth, others next to the door, coffee made the rounds twice, the women often controlled the conversation. But stern Elder Jones, the town doctor and First Baptist Church minister, had the final word, “We must reach high. Let the other towns welcome these poor farmers.”

Narrator: I can see the crowded living room in my dream, the activity and talk that waned and waxed, the heat that drifted out into the fields as night progressed. She rocks me gently by shifting her broken timbers, her broken bones. Like Emerald over a hundred years before, I lean into her, look through her eyes, out her windows. And then I see them, another group of people who will arrive in the future, ragged and tired, migrants and refugees.

MUSIC:

Oh, give me a home, where the buffalo roam

and the deer and the antelope play

Historian: This quintessential American song was recorded and published by John Lomax, but it was first performed and most likely first written by a black saloonkeeper and cowboy from San Antonio, Texas.[4]

House: Emerald read every book she could get her hands on, from neighbours, from school, by mail order. But it wasn’t book smarts that guided her. I watched her stare at nothing and could tell she was catching sight of people in other places like a gem capturing the sun’s reflected light from the moon. When she was 15, she heard a girl crying for help. The girl, she told her mama, had long black hair and wounded eyes. She huddled alone in the icy field, tiny in the broad expanse of white under black sky. The girl was losing her home – a home where she and her family, also from the South, had been forced to move. Now it was being taken away, along with her relatives. Night after night, the girl called to Emerald. No one else heard the cries. Still, the men went looking for the girl, only to futilely search the empty fields.

MUSIC:

The red man was pressed from this part of the West,

He’s likely no more to return

To the banks of Red River where seldom if ever

Their flickering camp-fires burn.

Historian: The Dawes Act passed in the US Congress in 1877, taking away reservation lands from indigenous people and subdividing them into individual plots. Unlike the Homestead Act which required five years of successfully working the land to gain full ownership, The Dawes Act required indigenous people to spend 25 years working the land and they had to behave like White Americans to gain ownership and citizenship rights. Native Americans lost 80 million acres through this allotment system, and in the American scrum to survive, African Americans, like white Americans, laid claim to their land.

MUSIC:

Where seldom is heard, a discouragin’ word

And the skies are not cloudy all day.

House: It wasn’t just the girl in the field whose story turned out to be true, Emerald also predicted what would happen with the railroad. The townspeople knew that if the railroad came to Ezana, they would prosper, and so they painstakingly raised a $15,000 bond as a lure. Emerald said no matter the amount of money, the railroad would never come to them, and she was right.

To some of the townspeople, Emerald’s clairvoyance was spooky; to others, calming. But her silence seemed to confuse everyone: her neighbours speculated about its cause, predicted its endurance. Many said Emerald would never speak, especially after what happened to Ray.

MUSIC:

How often at night, when the heavens are bright,

With the lights from the glitterin’ stars.

House: Stocky and strong from the time he was born, Ray lived two houses down and, once his legs would carry him, he visited every day. When the kids were little, he’d leave grasshoppers in Emerald’s bed; as they grew older, he and Emerald’s brother would sit on the porch dreaming of marriage, becoming doctors, owning their own homes and then they’d run into the fields, hollering with the uncontrollable exuberance of youth. Ray’s favourite pastime was playing with Sponge, the tabby cat. He would twirl a strand of white worsted in front of her while sitting on my front porch.

Because the prairies offered little beyond sustenance, the people of Ezana had to travel to white towns to buy some items, like the wood used to build me. Ray began asking to make the treacherous trek when he was 14. It took three years until his parents and the community agreed to let him go. He knew the rules, of course he did, and followed them…at first. He walked to the white town during daylight, running much of the way in his excitement. He purchased fabric, nails, a muffin tin, and other items on his list, and headed back toward Ezana as the sun began its descent. He stopped halfway for the night at the dugout, pulling the door shut and latching it from the inside. According to what Emerald told her mama, the dugout felt too constricting. He became restless, wanted to go out into the infinite openness of flat land and curved sky, smell the grasses as the temperature dropped, listen to the heartbeat of crickets, watch for a slinking coyote, gaze at the stars. He wanted to feel his freedom.

Emerald said the white men found him because he glowed like moonlight. She wouldn’t say more than that, but the knowing was in her body. Mention of Ray caused her to convulse.

The townspeople panicked when he didn’t return. The men went looking for him day after unresolved day. His body never came home. The only remnant of Ray was a strand of white worsted in a buckthorn bush by the dugout. There was no proof he was murdered. Still, everyone knows why someone like Ray who loves his home doesn’t return.

Once the initial intense sorrow passed, the family focused on me, as if I were the answer to recovery. They repaired my tired porch and painted me white again. But after Ray’s disappearance, most of the younger people took their strong sense of community and good educations and left Ezana. Within the year, Emerald planned to go to Tulsa with her brother and a friend. She told her mama white hate was too virulent for my walls to withstand. She was also keen to the agitation underground below my foundation where shovels had bumped into the bone dust of the original peoples.

On a quiet spring day, Emerald took a sharp, grapefruit spoon from the kitchen drawer and found a spot of me turned soft by years of steam from boiling pots. She dug into my porous skin and carved out a round groove the size of a tiny acorn. She placed that piece of me in her small, stiff, grey suitcase, clamped the suitcase shut, grasped the oily handle in her slim, delicate hand, and pushed my front door open. The screen door, which ripped the next month and would never be repaired, bounced shut behind her. Through my windows, I watched her disappear, tiny puffs of dust rising where she stepped. I wonder about that piece of me that she took: was it for remembering or forgetting, to carry along or deliberately leave behind?

Our once vital town was soon overtaken by ghosts. My bones began to ache, my muscles tighten, the skin holding me together sagged, weather beaten and tired.

Narrator: I interrupt her to tell her that we’d met before, many years past when she was still standing. I was visiting two of the remaining fourteen residents — a 75-year-old woman, who smelled of rose water and sat properly stiff-backed on an embroidered piano bench, and a wiry, nervous man a bit older than the woman, who leaned toward me from a worn green fabric chair. The door was open that day; the hot, thin air so still it remained on the doorstep like the sleeping cat.

House: Yes, I remember. There were already few of us then … the First Baptist Church’s white paint had scaled like fish skin, the hotel, which once bustled as a post office, stagecoach stop, and schoolhouse was hollow and boarded. Only a patch of the wooden walkway remained in front of the old ice cream parlour. The few white plastered homes had blistered; those made of wood worn to thread.

Narrator: The couple I met also seemed translucent, or at least in my memory. Sitting in the unlit room, blinds drawn, doilies mustard-coloured from age, plastic furniture coverings yellow, brittle, and cracked, they bickered about the town’s history as if conflicting memories could keep their dying town alive. The skinny woman handed me a tired file folder with tattered newspaper articles, a browned pamphlet printed many years before, a list of the first families. The papers had been touched by so many hands the fingerprints glowed iridescent.

House: We thought you would tell our story, but never heard from you again.

Narrator: Your story is not mine to tell.

House: Remember it’s only a dream.

Narrator: In the dream, you disappear in my rearview mirror, like Emerald disappeared and the older woman and man sitting in half-lidded light, and the cracked, abandoned homes, everything melding with the horizon into dusk and the open plain. The sky has returned to its incessant, undisturbed blue, now paled by late day. I drive the ten miles to the highway that parallels the railroad tracks, that vein of life along which all-white communities flourished. I pass the shadows of hundreds of people moving north, looking for homes, the dead like the living.

House: Maybe one shouldn’t grasp for hope but rather allow for redemption[5] … at least when reconstructing a house.

Narrator: The action of saving or being saved from sin, error, or evil; of regaining or gaining possession of something in exchange for something else. Why redemption? scholar of Black history. Shouldn’t redemption be sought only by the white Americans who built hate into the landscape, the houses, the bodies, the souls?

Historian: It’s never a simple story.

Narrator: I wonder if we will all be refugees, like the people of Ezana, forced to live differently, outside what we are familiar with, but in the future carrying luggage that holds redemption.

House: I have no door. No walls, no definition. The lids of my eyes are gone. More migrants may arrive, more hands build together, and I may be constructed anew. But for now, I rest in the earth.

MUSIC:

Have I stood here amazed, and asked as I gazed

If their glory exceeds that of ours?

Home, home on the range

Where the deer and the antelope play…

*

I’ve been writing, in one form or another, all my life. My favorite is fiction or near fiction, or fantasy non-fiction, a genre I cuddled up to later in life. My first job out of college was writing for the Village Voice. I then wrote (produced and directed) documentaries and biographies for broadcast for 15 years in NYC. I’ve written for radio, for blogs (including my own about traveling for a year) and podcasts. After moving to Canada, I wrote for the Vancouver Observer and the National Observer. I finished the first version of my first novel, Thin Lines of Broken Time, four years ago, and have been rewriting it ever since. It’s humbly looking for a publisher. Anne Depue, a Seattle-based literary agent, represents my fiction. I’m also a visual artist, the visual and written in constant communication with each other in my work. I’m currently writing a second book about life in motion and its relationship to ideas of home.

*

The British Columbia Review

Editor and Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/why-very-first-treaty-between-us-and-native-people-still-resonates-today-180969157/

[2] Dennis Zotigh, “A Brief Balance of Power: The 1778 Treaty with the Delaware Nation,” Smithsonian Magazine

[3] Alwyn Barr, Black Texans: A History of Negroes in Texas, 1528-1971 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), page 4, footnote 6

[4] https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2022/03/black-cowboys-at-home-on-the-range/

[5] Like the character of Furiosa in the film, Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)