1700 Freedom Convoy: out of options?

An essay by Brian Smallshaw:

Out of Options with the Freedom Convoy?

*

Whatever you think about the Freedom Convoy’s occupation of Ottawa and the blocking of border crossings in Windsor and Coutts, the Canadian government’s decision to invoke the Emergencies Act to shut down a protest should be of concern to every Canadian who values the protections against authoritarianism guaranteed by our Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Written into the Emergencies Act is a requirement that public hearings be held after it is rescinded to determine if the government was justified in invoking it. These hearings, known as the Public Order Emergency Commission, are currently underway in Ottawa.

By mid-February of 2022 the dire situation in the nation’s capital and several important border crossings required a decisive response. For weeks big diesel trucks had been running round-the-clock on and near Parliament Hill, air horns were blasted day and night, people were carrying jerry cans of fuel near bonfires in the streets, local business people were being intimidated and harassed, and all the while the police seemed helpless to control the situation—and worse, seemed to be in sympathy with the protesters.[1]

Something had to be done, and on February 14th, Valentines Day, Prime Minister Trudeau invoked the Emergencies Act, a government spokesperson declaring that it had only been done after “the deliberate step-by-step process in which careful consideration was given to all the available options” [“Inquiry on Trudeau Using Emergency Powers on Trucker Protests Begins” New York Times 13 October 2022].

All the available options? Really?

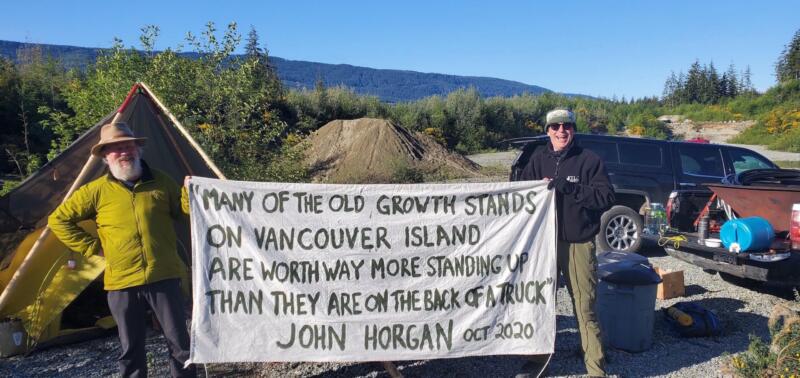

Only half a year earlier I witnessed a variety of options that were successfully used to disperse a very large, drawn-out protest at Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island, options that were never employed in Ottawa, Windsor or Coutts. The diverse collection of citizens trying to prevent the destruction of ancient forests were only disrupting the lives of a few loggers and quite a few RCMP officers, but they were much more harshly dealt with than the truckers who had brought our country to a standstill, and the Emergencies Act was not invoked. Why the difference?

I was not involved in the ‘Freedom Convoy’, but the year before when I learned that plans were afoot to destroy the last untouched valley of the San Juan River watershed in southern Vancouver Island I felt I had to express my opposition. Years from now I wouldn’t be able to look my kids in the eye if I did nothing while they brought down some of the last remaining giants of the west coast. I am a historian who has researched and published on the use of the War Measures Act, which the Emergencies Act replaced, to dispossess Japanese Canadians of their property during the Second World War[2]. History teaches us that bad things can happen when good people sit back and say nothing in the face of injustice.

The protests at Fairy Creek received far less media coverage; but they were on a very large scale, they went on for months and approximately 1200 people were arrested before the RCMP were able to remove the protesters from the logging roads and bring the protests to an end.

This was done without invoking the Emergencies Act. Why weren’t the techniques the RCMP used at Fairy Creek employed against the protesters in Ottawa? Was it because police actions that violated Charter rights and freedoms would receive more public and media scrutiny in Ottawa, because such actions were more likely to have provoked violence among protesters, or for some other reason?

The protests and the circumstances in which they took place were very different at Fairy Creek and in Ottawa; at the former, the protesters were people opposed to logging in the last untouched watershed in the San Juan River Valley, while in Ottawa the protesters were opposed to government mandates aimed at reducing the number of deaths and hospitalizations during the pandemic. The former was entirely peaceful, while the latter was not. The Fairy Creek protesters inconvenienced the Teal Cedar logging company, while the Freedom Convoy protesters made life a misery for the citizens of Ottawa and brought our capital city to a standstill for weeks.

In Ottawa the police treated the protesters more gently, and many of the officers involved were apparently sympathetic with their cause, going so far as posing with them for social media selfies.[3] Some politicians too were on side with the protesters — Pierre Poilievre, now the leader of the Conservative Party, met with protesters to demonstrate his solidarity.[4] By contrast, the police at Fairy Creek were given permission by their commanders to not display name tags or badge numbers as required by RCMP regulations, for fear that they would suffer threats on social media.[5]

Yet in certain respects the two protests were similar. Both involved large numbers of protesters who were not organized into unified wholes; both saw large numbers of protesters occupying public roads for long periods; both were defying injunctions against them. Given that the Fairy Creek protest took place on remote logging roads in British Columbia and the Freedom Convoy protests took place in the heart of Ottawa, it is understandable that police actions against the two protests might be different, but one may still wonder why some of the techniques used by the RCMP at Fairy Creek weren’t applied against Freedom Convoy protesters.

Some of the police actions at Fairy Creek were:

1. A large tightly controlled exclusion zone. At Fairy Creek the RCMP established an exclusion zone of many hundred square kilometres[6]. An exclusion zone of this size wouldn’t have been possible in Ottawa, but given the far greater resources available to the police in Ottawa certainly they could have cordoned off something larger than the ‘Red Zone’ around Wellington Street and strictly controlled all access in and out of the area.

2. ID and bag checks at entrances to the exclusion zone.

At Fairy Creek the RCMP established checkpoints in which everyone wishing to enter had to produce ID and allow their bags to be checked to ensure that they were not carrying concrete, pipe or other materials that were used by protesters trying to blockade the road. In Ottawa there were grave concerns about protesters carrying in jerry cans of fuel in an area where people were having bonfires and shooting off fireworks, as referenced many times during these hearings [Oct 21, Transcript lines 14, 24, among others]. Despite this, the police were reluctant to stop even those obviously carrying fuel. At these hearings on October 25th Ontario Provincial Police Interim Superintendent Marcel Beaudin said, “I don’t think charging someone with a jerry can offence is going to open roads or get people to leave.” [Transcript lines 15-17]. Yet at Fairy Creek, refusing to submit to a bag check led to your arrest and removal from the area—which happened to me. Yet in Ottawa, despite the threat to public safety, people carrying jerry cans of fuel to protesters were not challenged, must less arrested.

3. ‘Catch and Release’ arrests.

At Fairy Creek many hundreds of people were arrested, not charged with a crime, and then transported away from the protest site. These came to be known as ‘catch and release’ arrests. Was this not done in Ottawa because such a violation of Charter rights would be more visible to the public?

4. Pepper spray.

On August 21, 2021 protesters who had locked arms near the entrance to the Granite Main logging road were pepper sprayed by the RCMP to remove them.[7] The RCMP’s assertion that this was required because one of their personnel needed to be medically evacuated was later proven to be false.

5. Use of heavy equipment to remove protesters.

At Fairy Creek protesters who were locked into the road or on log tripods blocking the road were removed using excavators and jack hammers. Many vehicles were towed from where they were situated on logging roads. There have already been many questions about why the Ottawa police did not tow trucks parked on Wellington Street, but why didn’t the police use excavators and Community-Industry Response Group (C-IRG) tactical police forces to remove protesters from their trucks in Ottawa? When I witnessed the RCMP situate a large excavator bucket over the head of young woman seated on a log tripod and then drop a C-IRG police officer onto the tripod to forcibly remove her, I was assured by District Liaison Team Officer Cunningham that it was safe.[8]

6. Removal and/or destruction of protesters’ property.

At Fairy Creek, C-IRG and Teal Cedar-employed personnel were used to remove or destroy vehicles, camping gear and other equipment, in order to discourage protesters.

None of these actions was taken in Ottawa, Windsor or Coutts before the invocation of the Emergencies Act. The Freedom Convoy protests had far more serious consequences for the people of Canada than the Fairy Creek protest—they were shutting down the nation’s capital and important border crossings, not just preventing a logging company from cutting some old-growth trees. Yet they were handled so much more gently: no pepper spray, no tactical police officers removing protesters from their vehicles, nobody arrested and removed from the area for refusing to be searched at a checkpoint. Why did the government and police act so differently at the two protests?

It wasn’t because they were simply unaware of these methods for dealing with protesters. From OPP Interim Superintendent Marcel Beaudin’s testimony at the POEC hearings on October 29th [Transcript line 26] I learned that he regularly consulted with his colleague in BC, Chief Superintendent John Brewer, Gold Commander of the C-IRG, who oversaw police enforcement at Fairy Creek and We’suwet’en, so surely he was aware of their methods.

Was it because they were constrained by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

As stated by the Government of Canada counsel Andrea Gonsalves on the October 25th session of these hearings, in Ottawa the police could not undertake actions which were “inconsistent with our constitutional structure” [Transcript line 18-19], which I understand to mean actions that would violate protections guaranteed to Canadian citizens under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This was confirmed by Interim Superintendent Marcel Beaudin [Transcript line 21 “There’s limitations to the Constitution for sure.”].

Fairy Creek is a long way from the capital but it’s still in Canada, yet the RCMP didn’t seem to suffer from the same constitutional limitations. In their testimonies in the POEC hearings, police and government officials have stated that they were reluctant to arrest protesters in Ottawa and Windsor because they were worried that the officers might be ‘mobbed by protesters’. At Fairy Creek, the RCMP arrested hundreds of protesters, didn’t charge them with a crime, hauled them away to Cowichan Lake or Port Renfrew and released them. These ‘catch and release’ arrests as they came to be known didn’t happen in Ottawa or Windsor. Overall, about 1200 people were arrested at Fairy Creek in 2021, far more than were ever arrested in Ottawa, Windsor and Coutts, even after the Emergencies Act was invoked. For Fairy Creek protesters who saw what happened in Ottawa, the conclusion might be that being resolutely peaceful was a mistake—had there been a threat of violence at Fairy Creek maybe they would have been treated with more care by the police. This is a disturbing thought, and is not a conclusion that we hope protesters come to in Canada.

Though both protests were very large and ‘organic’ in their organization, in important ways they were different.

The Freedom Convoy protesters were against the government mandates aimed at containing the spread of COVID-19 and reducing the number of deaths in the pandemic. The Fairy Creek protesters were trying to pressure the government into ending old growth logging, and preserving the remaining 3 percent of bottomland ancient forest in British Columbia.

The Freedom Convoy protesters were concerned about the threats to their livelihoods posed by the mandates; the Fairy Creek protesters were concerned about the loss of ancient forests, biodiversity and climate change. The protesters in Ottawa, Windsor and Coutts were upset about personal losses that they were suffering; the protesters at Fairy Creek were trying to save the planet.

The police officers tasked with enforcement at the two protests were clearly more sympathetic with the Freedom Convoy protesters than the Fairy Creek protesters. As someone who was at Fairy Creek, I was struck by the number of police officers and politicians who posed for selfies with the Freedom Convoy protesters. From the POEC hearings we learn that members of the police forces were even passing information to the protesters. This never happened at Fairy Creek. Was this because the police felt more of an affinity with the truckers and loggers than they did with the young people, Indigenous people and seniors who formed the bulk of the Fairy Creek protesters?

The locations of the two protests were very different; a logging road in British Columbia versus the streets in front of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. At Fairy Creek the establishment of a tightly regulated exclusion zone allowed the RCMP to restrict the access of the media,[9] already difficult because of the remote location. By contrast, the actions of both the protesters and the police were under close public and media scrutiny in Ottawa.

Some of the methods used by the RCMP at Fairy Creek were violations of Charter rights and freedoms. At the point where the Granite Main logging road meets the Pacific Marine Highway about 15 kilometres from Port Renfrew and more than 10 kilometres from where the Fairy Creek logging was to take place, the RCMP established a checkpoint where anyone wishing to enter the exclusion zone that they had set up were required to show ID and submit to a search of their packs. Without the invocation of the Emergencies Act this was a violation of Section 8 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms: Everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure. On September 7th 2021 I was arrested for refusing to submit to a search and transported to Port Renfrew and released. I was not charged because I wasn’t breaking a law. Close to a thousand people suffered similar treatment at Fairy Creek.

Equal application of the law is a central pillar of our legal system, as guaranteed by the Charter,[10] but nothing like these violations happened in Ottawa, Windsor or Coutts. This was because Charter violations would be in front of the media and subject to close public scrutiny. Had the police arrested people on Wellington Street without charges and transported them out of the city, it would have affirmed the contention of the Freedom Convoy protesters that the government was becoming authoritarian. If the police had used pepper spray to dislodge truckers from their vehicles it would have instantly been on every media outlet in the country, and all police declarations about being committed to safety and non-violence would have been revealed as a sham. Instead, they decided to invoke the Emergencies Act to suspend civil liberties and temporarily become authoritarian.

Was it justified? Certainly the situation demanded that something be done, but as Canadians we should be deeply concerned about the precedents that have been established in both of these protests. In one, the government was willing to violate Charter rights because it was operating with little media or public scrutiny. In the other, the Emergencies Act was used to suspend Charter rights in order to shut down a protest. As has been regularly stated at the POEC hearings, Canadians have the right to engage in peaceful protest. At Fairy Creek, where the protests were peaceful, Charter rights were violated to shut them down. In Ottawa, Windsor and Coutts, where the protests were not peaceful, Charter rights were suspended to shut them down.

*

Brian Smallshaw is a historian of the Japanese Canadian uprooting during World War Two. In his book, As If They Were the Enemy, he undertook a detailed analysis of the legal mechanism that was used under the War Measures Act to dispossess Japanese Canadians of their property while they interned in the British Columbia Interior. He is also very interested in environmental issues and was involved in the protests to protect the old growth forests of Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island in 2021. With this background, the Canadian government’s decision to invoke the Emergencies Act, the successor to the War Measures Act, in order to terminate protests in Ottawa, Windsor and Coutts was of great interest. He lives with his family on Salt Spring Island. Editor’s note: Brian Smallshaw’s book As if They Were the Enemy: The Dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island is reviewed by Marie Elliott and his book (with Rumiko Kanesaka) Island Forest Embers: The Japanese Canadian Charcoal Kilns of the Southern Gulf Islands is reviewed by Robert Muckle.

*

Endnotes:

[1] ‘OPP officer lets protesters take photos in back of police cruiser’ CBC News 11 February 2022

[2] As If They Were the Enemy: The Dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island, University of Victoria 2020

[3] ‘Are police officers helping the “truckers” protest?’ Peace Quest 4 February 2022

[4] ‘Carleton MP Pierre Poilievre Endorses Downtown Anti COVID-19 Demonstrations’ Manotick Messenger 4 February 2022

[5] Correspondence with Chief Superintendent Steven Ing, 3 August 2022 “E” Division RCMP “In light of the confirmed incidents of threats and harassing behaviour on social media, as well as threats to their personal safety, homes, and family, RCMP members tasked to police the Fairy Creek Watershed protests were advised by their Command Team that they did not have to wear name tags.”

[6] The large exclusion zone was ruled to be illegal by Mr. Justice Thompson in his decision of 9 August 2021, to which the RCMP responded by reducing the size of their exclusion zone in areas where protests were not taking place. See bccourts.ca

[7] See here for video footage of RCMP pepper-spraying protesters.

[8] It seemed obvious to me that this was not safe, and in fact, it violates OHS Regulation Part 16: Mobile Equipment.

[9] The RCMP restricted media access until ordered by a judge to grant full media access; see CBC story here.

[10] Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Section 15: “(1) Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1700 Freedom Convoy: out of options?”

“The diverse collection of citizens trying to prevent the destruction of ancient forests were only disrupting the lives of a few loggers and quite a few RCMP officers, ….” These citizens were also disrupting the lives of the Indigenous peoples on whose territories they were protesting. At the time, the protestors ignored repeated requests to leave from the government and hereditary Chief of the Pacheedaht First Nation (supported by the governments and hereditary Chiefs of the adjacent Ditidaht and Huu-ay-aht First Nations). Judging by this essay, they still refuse to acknowledge the Aboriginal Rights and Title of these First Nations or admit the harm they did to them.

Not to put too fine a point on it but from where I sit, the so-called “Freedom Convoy” was a drawn out three week and counting insurrection, an occupation not only of the streets of Canada’s capital city and seat of the federal government but of the attention of the entire country. Normal policing methods failed. To say that, “The Freedom Convoy protesters were against the government mandates aimed at containing the spread of COVID-19 and reducing the number of deaths in the pandemic,” minimizes the ranges of insurrectionist thoughts and deeds that were afoot. Our civil liberties are a prize possession. Brian Smallshaw seems more interested in the alleged abrogation of civil liberties at Fairy Creek than the means by which the occupation of Ottawa and other Canadian jurisdictions was finally ended.