1698 On Ruskin’s road

Imminent Domains: Reckoning with the Anthropocene

by Alessandra Naccarato

Toronto: Book*hug Press, 2022

$23.00 / 9781771667753

Reviewed by Graeme Wynn

*

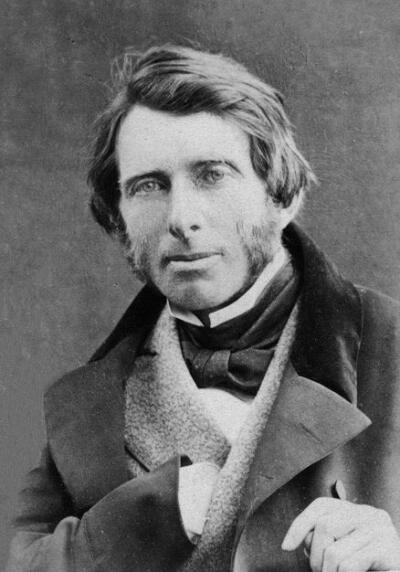

In the 1870s, John Ruskin, Slade Professor of Fine Art in the University of Oxford, initiated a scheme to improve the rough and muddy path into the village of North Hinksey on the outskirts of the “city of dreaming spires.” The project was an unusual one. Although it probably began on a whim, it reflected both Ruskin’s desire to improve society and his conviction that there was something pleasurable and noble about muscular work. Building a better road would beautify and improve the village and exemplify the benefits of useful toil. The road-makers (known as Ruskin’s “diggers”), were volunteers, students recruited from Balliol and other Oxford colleges. Individuals joined the venture for various reasons, and their efforts were a source of amusement to other students and to Punch magazine, but most became “dévots” of Ruskin, basking in his aura and absorbing his ideas; the professor, it has been said, had “a genius for discipleship.” Through “the mist and rain and mud of an Oxford winter,” the work continued, sometimes with Ruskin present, at other times following his instructions sent from Italy. Stones were broken, drains laid, and muscles exercised. The road was not entirely well made – the best that a local surveyor could say was that “the young men have done no mischief to speak of.” Nor was it ever completed. So what became of it? Oscar Wilde, who wrote an amusing, if not entirely accurate, account of its making (although he may not have participated in that) offered a memorable answer: “Well, like a bad lecture it ended abruptly—in the middle of the swamp.”

In the 1870s, John Ruskin, Slade Professor of Fine Art in the University of Oxford, initiated a scheme to improve the rough and muddy path into the village of North Hinksey on the outskirts of the “city of dreaming spires.” The project was an unusual one. Although it probably began on a whim, it reflected both Ruskin’s desire to improve society and his conviction that there was something pleasurable and noble about muscular work. Building a better road would beautify and improve the village and exemplify the benefits of useful toil. The road-makers (known as Ruskin’s “diggers”), were volunteers, students recruited from Balliol and other Oxford colleges. Individuals joined the venture for various reasons, and their efforts were a source of amusement to other students and to Punch magazine, but most became “dévots” of Ruskin, basking in his aura and absorbing his ideas; the professor, it has been said, had “a genius for discipleship.” Through “the mist and rain and mud of an Oxford winter,” the work continued, sometimes with Ruskin present, at other times following his instructions sent from Italy. Stones were broken, drains laid, and muscles exercised. The road was not entirely well made – the best that a local surveyor could say was that “the young men have done no mischief to speak of.” Nor was it ever completed. So what became of it? Oscar Wilde, who wrote an amusing, if not entirely accurate, account of its making (although he may not have participated in that) offered a memorable answer: “Well, like a bad lecture it ended abruptly—in the middle of the swamp.”

I have been thinking of Ruskin and the Hinksey Road (to say nothing of bad lectures) a lot lately. I am one of a small group of volunteers from the UBC Emeritus College engaged with others from across the university in an initiative of the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Study. We are in misty, wet Vancouver, and our labour is intellectual rather than physical, but we, like Ruskin’s diggers, hope to develop a route to a better future. Our challenge – the metaphorical swamp through which we need to find a way – is the Climate and Nature Emergency, and it is of a scale altogether different from that of the muddy floodplain of Hinksey Stream. Two United Nations’ conventions – COP 27, on climate, held in Sharm el Sheik, Egypt, in November, and COP 15, on biodiversity, convened in Montreal in December of 2022 – mark the global scope of these issues. Considered separately, these two concerns are somewhat at odds. Anxiety about global warming is high, and much attention is focussed on this, but efforts to limit heating are ultimately about ensuring a future for humans; climate change is not the main cause of biodiversity loss, most of which is attributable to resource development, over-extraction, and habitat loss. “Addressing climate change will not ‘save the planet’,” is the simple conclusion of a recent study. Twinned, as they often are, however, these two crises are integral elements of the broader calamity that confronts the twenty-first century world, a calamity ever more widely characterized, in popular discourse, as “The Anthropocene” — an epoch defined by humankind’s impact on the biosphere.

Chipping away at these concerns, we confront hope and despair. The “solutionists” among us believe that scientists, engineers, politicians, and visionaries will open a path to survival: solar panels, wind turbines, hydrogen cells, even it seems (as of this December 2022 and according to the US’s National Ignition Facility) nuclear fusion, controlled and harnessed on earth, will substantially eliminate the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Earth For All, a new report to the Club of Rome (that commissioned The Limits to Growth in 1972) identifies “five system-shifting steps that can upend poverty and inequality, lift up marginalized people, and transform our food and energy systems by 2050.” Touted as a road map to a better shared future for humanity, it insists that collapse is avoidable, if we act now and act decisively.

Doomists place us on a road to ruin (or as UN General Secretary Antonio Guterres had it in Sharm el Sheik, “on the highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”). We have known the risks along this route for half a century, yet little has been done to mitigate them. “Fine words,” ‘tis said, “butter no parsnips”: emissions targets have been set; agreements signed; and grave utterances made. Still greenhouse gas concentrations have risen, inexorably. Planetary boundaries, thresholds within which humanity can survive and thrive, have been defined — and exceeded. We are in a state of “global overshoot” (Rees, 2022). Too many people are consuming irreplaceable elements of the earth system at unsustainable rates. There may be no scientific basis for the claim that erosion will eradicate the fertility of Britain’s soils in 100 years (or 30 or 40 according to Environment Secretary Michael Gove reported in The Guardian on 24 October 2017), but we can no longer look forward to expanding plenty – or, indeed, to future prosperity. The current environmental crisis is so severe that significant disruption is unavoidable. We face an apocalypse, “and the only question now is how bad it will be” (Jackson and Jensen 2022).

There is no easy way to reconcile these conflicting views, but an invitation from the BC Review, to reflect on Alessandra Naccarato’s Imminent Domains: Reckoning with the Anthropocene, brings at least the promise of new perspectives. This short but thought-provoking book invites readers to join in the “contemplation of survival – our own and that of the elements that surround us.” What, I wonder, can the young poet and essayist offer us aging toilers as we seek to move our intellectual digging beyond an abrupt and unsatisfactory end in the middle of the morass that envelops us – and I try to save this essay from becoming a bad sermon?

First, it is reassuring to find that the poet regards contemplation, vision, and communication as crucial forms of labour. This, the work that artists do for – and that elders/emeriti should contribute to – society, is often overlooked, but always vital to “the strengths of our communities, and the paths we are choosing forward.” Naccarato’s genre-defying book, part memoir, part confessional, part travelogue, part manifesto, part meditation, and part embrace (of humanity, connection and kinship with a more-than-human world), soars and dips through time and space, experience and emotion, doubt and grief. Ultimately, perhaps it is about life in the thorny, tricky, challenging, and contradictory times in which we all live.

Naccarato’s “reckoning” is obviously deeply personal – and thus idiosyncratic. Published by Book*hug Press, in its Essais series intended to challenge traditional forms and styles of cultural inquiry, Imminent Domains invites reconsideration of, and reflection on, many established verities. The book is framed by reference to the four elements of matter (earth, fire, water, and air) to which is added a fifth, spirit (or mystery), that is intangible to our senses. These sections, each comprised of three short compositions that bear on one of the elements, are followed by a sixth section (titled “The Understory”) made up of short “companion essays” and research notes. All of this makes for a somewhat disjointed collection of more or less free-standing pieces rather than a single sustained line of reasoning. This gives the book an episodic, kaleidoscopic quality, that is, perhaps, a mirror of contemporary life.

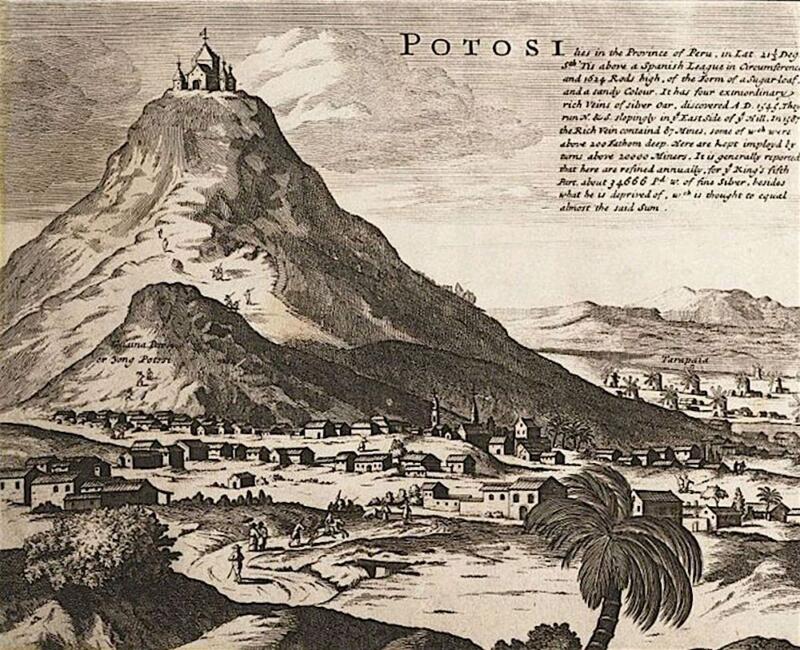

To my historical-geographical mind, several pieces in the first two sections of the book – “Keystone Ecotones (earth)” and “Mountains that Eat Men (fire)” – present (at their best) arresting, insightful perceptions in well-crafted even lyrical prose. Earth includes a discussion of deforestation that is really about ticks, Lyme disease, and zoonosis. A second piece called “Rewilding” explores the implications of living on the precipice of complete environmental collapse, and the impossibility of grieving a loss that spans our entire existence. The third focuses on the black-footed ferret to explore the politics of species extinction and the tangled ethics of cloning endangered and extinct species (or even beloved pets). Fire (men-eating mountains) I found particularly captivating. Its three compositions focus on the author’s visits to Pompeii in Italy (where 2000 people died when the town was buried by volcanic ash from Mount Vesuvius), and Cerro Rico, near Potosí in Bolivia (where eight million people are said to have died in the silver mines over the centuries), and on her fascination with healing crystals (“Blood Stones”).

These are all distinct, personal stories. As elsewhere in the book we learn a good deal about the author, her lovers, her experiences, and her fears. At times, I found myself wondering: Why this self-absorption, this narcissism, amid allusions to issues of much larger importance to the fate of earth and humankind? Salar de Uyundi, a salt flat in Bolivia, is a valuable source of lithium, an essential element in modern battery, and thus much digital, technology. A military coup that replaced a democratic, socialist government in 2019 may have been precipitated by a desire to control the resource. When wet, the salt-encrusted depression becomes a giant reflector. Stand then (on Naccarato’s pages 79 and 80), upon “the lithium flats…[and] see yourself wherever you go. Take a photo of the ground: it’s a selfie”. Perhaps my peevish reaction to this is a generational thing. Perhaps this is where those of us anxious about the fate of the earth and humankind need to be if our concerns are to be heard by those poised to make a difference to the future.

Fortunately, in my view, there is also good writing and penetrating insight enough in these pages to encourage pause and contemplation. Here, by way of example is Naccarato on silver mining near Potosi. After recounting her disturbing descent into the bowels of the earth at Cerro Rico in 2007 – a descent undertaken after an adventitious encounter with a guide from Green-Go Tours, operating as part of the survival “economy of witness,” as the silver dwindled (and mining jobs declined) – she couples recollections of that experience with contemporary developments to reflect on the implications of mining, tourism, and life characterized as a story that we enter “without understanding our place in it. Without knowing the harm, the risk, or the cost.”

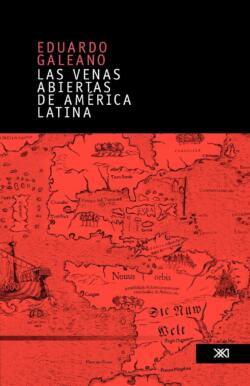

In part, these reflections are triggered by an advertisement dressed up as a report, published in the Financial Post on August 13, 2020, to tout the prospects of the Silver Sand property a short distance northeast of Cerro Rico, owned by Vancouver-based exploration and development company, New Pacific Metals Corp. The story opens with a (mis)quote attributed to Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, intended to emphasize the value of this find located amid a resource cornucopia barely 10 percent depleted: “You could build a bridge of pure silver from Potosí to Madrid with the amount of ore extracted” in the vicinity of Cerro Rico. The quote is also, Naccarato points out, incomplete. It omits Galeano’s telling and vitally important corollary: “and one back with the bones of those that died taking it out.” Naccarato is exasperated by this misuse of Galeano’s words to sing the praises of imperialism, when the man who wrote them was “obsessed with remembering” the violence of the imperial project. No-one knows how many died in the mines and mills of Bolivia, although the eight million often cited for Cerro Rico alone seems improbable. The point is that extraction exacted a terrible price. And in these times of human and environmental crises we cannot afford to look away, to nurture the sort of amnesia deplored by Galeano and represented by the selective use of his words – an amnesia, we now largely agree, that should never have been countenanced in the first place.

Potosí has been described as the first city of capitalism. Some have suggested that the dollar sign itself derives from marks imprinted on early silver coins from that city. That symbol shapes all of our lives. Adam Smith wrote about silver from Potosí in The Wealth of Nations, the foundational text of free-market capitalism. So a narrative was extracted from Cerro Rico along with silver, “and that narrative shapes the economy of our world” (p. 72). Its tentacles embrace us all. Even today, as the hollowed-out mountain crumbles in upon itself, as poverty-stricken “independent” miners toil in dangerous conditions for meagre returns, as tourists are encouraged to take their pictures within “Bolivia’s Most Deadly Mine,” and as multinational mining corporations hoping to operate nearby promise to develop micro-economies to benefit local communities, “everything taken from the mountain has a cost, be it silver or selfie or story” (p. 77).

Naccarato’s book begins with a story. She joins a group on a spiritual/ environmental retreat in a remote, bone-dry part of California during forest fire season. She is taken aback at the initial safety briefing. If the fire alarm sounded, everyone was to run back to the clearing. There they would grab shovels and head to the flames. Shocked, she wonders: “Who runs towards a fire? Without training, without protection, without water.” Reassurance is soon given. The best way to stop the fire is to dig a trench. In the absence of trained firefighters, equipment, and water, the group’s best chance lay in confronting the emergency together, in running toward the danger, using what they had, each playing the part they were able to take. Kinship, estrangement, and entanglement are at the heart of this response which is of course a metaphor for reckoning with the perils of the Anthropocene. The fire bell is ringing and we must respond. Even if our shovels are allegorical, we owe it to ourselves and others to confront the threat before us, and to play our parts in shaping the future of this precious sphere of interconnection and interdependence in which we live. “We are bound, sometimes chained, to systems and patterns of the world and its history” (p. 82). These structures, and the complexities of power that they produce will not be erased by good intentions or made to disappear by pretending they do not exist. The challenges are enormous, but as we turn toward them, Naccarato urges us to believe that “liberation and power” can be won through “relationships and interconnection.” To emphasize the point she quotes Ursula K LeGuin: “we live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but then so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings” (p. 206).

In his way, in his day, John Ruskin understood much of this. With his contemporary William Morris, and others, he worried about the costs, for the natural world and human existence, of industrial growth, technological advancement, and the rise of consumer society, and hoped for a different and better future than that toward which his society seemed to be heading. The Hinksey Road project with its twinned aspirations to beautify the countryside and to teach young men manual skills, was born of this concern. A few years after rousing his diggers to action, Ruskin advised a businessman to learn how to “plane and saw well,” because it was “an absurdity, waste, and wickedness” for people to “dig coal out of pits to drive dead steam-engines.” A decade before the road-building adventure, he asked readers whether they would forsake their garden lawns and flower beds for heaps of coke to increase their income. Assuming a negative response, he then reminded them that this was exactly what was taking place in the “little garden” that was England, in the name of progress and economic growth.

It was, Ruskin said, “the curse of every evil nature and evil creature to eat and not be satisfied.” He urged people to find contentment in modest comfort, to “satisfy themselves” rather than strive always “to better themselves” in order to ensure a better, more robust, future for humankind. Wise consumption was essential, as resources were finite. “There is,” he averred, “no wealth but life.” Ruskin had his disciples, in this as in road-building, but collectively they failed to carry their vision through the swamp of industrialization, consumerism, and estrangement from nature in which most of the world remains mired. It is time — past time — to recognize the cogency of Ruskin’s message, as reframed by Naccarato and many others. The prevailing ideology of economic growth must give way to an “ethos of artful simplicity.”

We need to find a course — to build a road — between indulgence and abstinence. The question is: How might this be done? Speaking, in the USA, to the National Book Foundation, Ursula Le Guin sought to rally her listeners by noting that “resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words” (p. 206). Interviewed during COP 15 in Montreal, former environmental activists Stephen Guilbeault and Zac Goldsmith, now government ministers with environmental portfolios in Canada and the UK respectively, stressed the importance of public protest in strengthening their environmental advocacy in cabinet – and thus in getting wise policies taken seriously. It is time to rally, with pen and placard and every other means possible, to counter the “affluenza” that ails us all and threatens the world.

*

Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he served as President of the American Society for Environmental History (2017-2019) and he is Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The British Columbia Review and as President of the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations. He was recently on the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College, and Principal of UBC’s Emeritus College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature| History| Society series published by UBC Press, and in 2019, under the On Point imprint of UBC Press, published a collection of essays, co-edited with Colin Coates, The Nature of Canada, reviewed here by Jenny Clayton. Editor’s note: Graeme Wynn has recently reviewed books by Laura Trethewey, Diane Pinch, Elin Kelsey, Mark Jaccard, Kevin Hutchings, and Alison Wearing for The British Columbia Review.

*

A note on related reading. Vicky Albritton and Fredrik Albritton Jonsson, Green Victorians: The Simple Life in Ruskin’s Lake District (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016) is the best introduction to arguments developed here; quotes are from pp. 8, 12, 22, 33, 88, and the “Introduction,’ pp. 1-20 is particularly helpful for the larger context. The term “Affluenza” was coined in the 1950s and has since come to signify the high social and environmental costs of materialism and overconsumption. For discussion of overshoot see W. E. Rees, “The human eco-predicament: Overshoot and the population conundrum,” Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2023, pp. 1-19; for impending apocalypse see Wes Jackson and Robert Jensen, An Inconvenient Apocalypse: Environmental Collapse, Climate Crisis, and the Fate of Humanity (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2022). For Ruskin’s road, see Bernard Richards, “Oscar Wilde and Ruskin’s Road,” The Wildean, 40 (2012), pp. 74-88. For efforts to arrest climate change being insufficient see Christopher Ketcham, “Addressing climate change will not ‘save the planet’,” The Intercept, December 3, 2022. — Graeme Wynn

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1698 On Ruskin’s road”

This review is for the most part fair, but I think it’s unreasonable for Wynn to claim that the book, which weaves personal experience with political commentary, is somehow “narcissistic” and “self-absorbed.” Given that the intermingling of personal experience and social analysis is simply the genre of the text, psychologizing the author seems unnecessary. It’s also difficult to ignore the gendered character of these adjectives.