1696 When empires collide

Converging Empires: Citizens and Subjects in the North Pacific Borderlands, 1867-1945

by Andrea Geiger

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2022

$35.95 / 9780774867993

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

When Empires Collide: How the Pacific Northwest was won, lost and sold

When Empires Collide: How the Pacific Northwest was won, lost and sold

Andrea Geiger takes readers to an early moment in Pacific Northwest history, one that sheds much light on how the lives of Indigenous peoples and immigrants were shaped and how they were forced to grab opportunities to reconstruct their survival in the wake of rapacious profit-hungry empires.

She has explored this complicated historical territory to uncover the clashes between American, British, Russian, Spanish and Japanese empires since 1867. These imperial powers were set not on carving up the northwest so much as usurping it for themselves. Various circumstances — legal, geographical, economical, military and racial — intervened to further threaten the working people, especially the Indigenous population, who claimed the space as their natural home.

The first part of the book explores these circumstances. For example, we learn about Russian America and the rivalry for furs, fish, sea otters, and land. The Russians eventually leave the region with the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867 for $7.2 million, but the Russians are in competition with the Japanese for the natural spoils of the Pacific Northeast.

As the empires clash, their governments use legal and illegal means to remove Indigenous people from their ancestral land to make way for commercial exploitation. The changing boundaries displaced Indigenous people but also offered paid work opportunities to supplement their diminishing ability to survive off the land. However, these came at the precious loss of their cultural heritage.

We also learn much about the impact on the Indigenous and immigrant communities of the scramble for gold in the Cariboo, the Klondike and elsewhere. But often it is through Geiger’s use of personal stories. Arichika Ikeda, for example, offers his view of the scene. A well-educated young Japanese man who travelled to the Klondike to join the rush, he was disgusted by the “vulgar and ‘truly low-class’ behaviour” he found there.

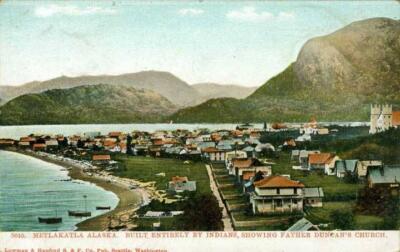

Ikeda also witnessed how the Haida and Tsimshian were “among the first Indigenous people to be caught in the shifting legal landscape” with their forced move to New Metlakatla on the northern borderlands. There and elsewhere the First Nations engaged “in complex acts of repositioning as they negotiated the tangled mix of constraint and opportunity.”

Other First Nations would suffer the same fate, but not without a fight. During the gold rush era, the Chilkat Tlingit First Nation offered “continued resistance to foreign intrusion.” This included “a reluctance to convert to Christianity for fear that this would render them little more than slaves.” They considered the Aleut of Alaska were enslaved by the Russians. Social structure and cultural traditions and a “strong clan system” provided the Tlingit with the power to resist through a sense of “solidarity against a common enemy.”

With neither Canadian nor American governments willing to accept their claims of natural ownership or grant them full citizenship, First Nations were caught between two “Converging Empires.” And those empires did not hesitate to use “violence and the threat of violence to displace Indigenous people who stood in the way of their access to land or resources.”

A pointed example is the attempt to remove the Tlingit from the tiny village of Wenah on Atlin Lake near Skagway, Alaska. Geiger uses Chief Taku Jack, the band leader, to relay the story of how the local Board of Trade attempted to remove them by telling a commission that “the desire of the white inhabitants to have their natives removed from the Atlin townsite.” The band held fast for decades.

Geiger explains how the Japanese government mistreated the Ainu people in Hokkaido in much the same way as U.S. and Canadian governments did. “Meiji officials justified their seizure of Ainu lands by characterizing the Ainu as a backward people in need of protection.” They viewed them, along with North America’s Indigenous peoples, as “doomed to extinction.”

In the second part of the book, Geiger focuses more intensely on the experiences of Asian immigrants, providing details about North American treatment of Asian gold seekers, fishers, cannery workers and settlers. Here we see legislators striving to pass laws that limit Japanese and Chinese participation in the new land and eventually restrict it with head taxes and a refusal of citizenship.

White mining, forestry and fishery workers, sensing that new immigrants threatened their livelihoods, pushed politicians to enact racially based laws. Geiger cites the notorious Asian Riot of 1907 in Vancouver and the Komagata Maru incident in 1914, when Muslim, Punjabi, Hindu and Sikh immigrants aboard a Japanese tramp steamer were refused landing rights to their hoped-for new home.

A unique aspect of Geiger’s in-depth treatment is her use of individual stories to describe them. In this way, she goes beyond the documentary record or the judicial one to provide the register of human misery, courage and innovation.

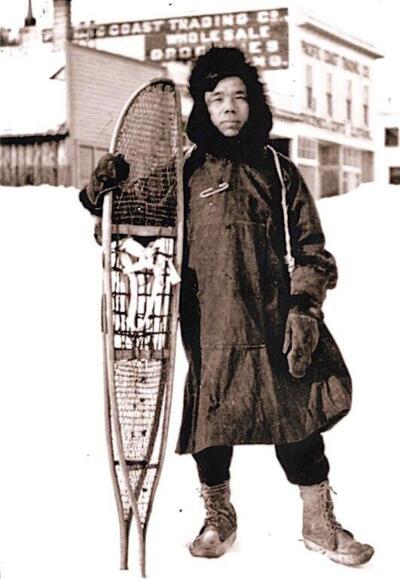

Jujiro Wada is another example of a Japanese adventurer whose story illustrates the social landscape facing immigrants. Abducted to work on a whaling ship in Alaska, he later embraced Inuit culture in the region and learned from them how to adapt to his new home.

As she notes, focusing on Japanese migrants like Wada, “permits a closer examination of ways in which they understood their presence in the North American West.” Interestingly, that focus also allows her to address “the reciprocal question of how Indigenous people perceived Japanese immigrants — as colonial settlers whose presence was not qualitatively different from that of Euro-Canadian or American settlers or otherwise.”

The book ends in 1945, but not without a riveting suggestion. It was the view of some Japanese leaders that the refusal to allow Japanese citizenship under the 1924 U.S. Immigration Act was one of the reasons for the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Geiger quotes other historians who argue that those U.S decisions “were nationally resented as racial insults and helped to bring on Pearl Harbor,” and that Japan’s response to the 1924 act “was one of the principal causes of the deadly clash.”

Photos and maps assist us in understanding the borderland disputes and in positioning the events that shifted First Nations communities from one region and even one country to another. The Metlakatlan removal story mentioned earlier, for example, is more easily visualized with such guides, as is the Wenah village story.

From today’s vantage point, we can now more clearly see the impact as conflicting international interests converged to make the Pacific Northwest region a contested territory. However, one thing is crystal clear: all the nations vying for possession of the territory were stealing land that already belonged to Indigenous peoples be they Anui, Aleut, Tsimshian, Tlingit, Inuit or other First Peoples.

Geiger has forcefully exposed that theft in a studied and well-documented book, revealing the true human cost of settling the greater Pacific Northwest region. It was high indeed

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker. His forthcoming book Printer’s Devils (Caitlin Press, 2023) tells the 30-year social history of the Trail Creek News, a feisty pioneer newspaper in Trail. His recent book, Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for its Life in Wartime Western Canada (University of Toronto Press, 2022), was reviewed by Bryan D. Palmer; an earlier book, Codenamed Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb (2018), was reviewed by Mike Sasges. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Jean Barman, Sarah Berman, Wayne Norton, Mark Hume, Michael Gates, and Jesse Donaldson & Erika Dyck for The British Columbia Review, and he has contributed an essay on trade unionist Harvey Murphy. Ron lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1696 When empires collide”