1679 Mary Welsh’s inheritance

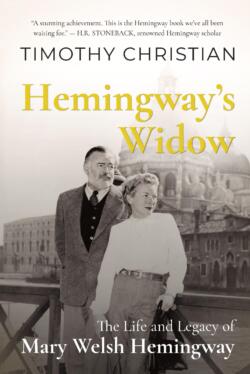

Hemingway’s Widow: The Life and Legacy of Mary Welsh Hemingway

by Timothy Christian

Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2022

$42.95 / 9781459750548

Reviewed by Peter Hay

*

Few books survive to become classics; their fame is most oft interred with the authors’ bones. Even fewer writers lead interesting enough lives to create a whole industry of biographies, memoirs, movies and scholarly studies. Ernest Hemingway stands out among those few.

Few books survive to become classics; their fame is most oft interred with the authors’ bones. Even fewer writers lead interesting enough lives to create a whole industry of biographies, memoirs, movies and scholarly studies. Ernest Hemingway stands out among those few.

The legend of Papa Hemingway began well before he placed a hunting rifle under his chin and blew his head off just before his sixty-second birthday. Apart from his books, he was already famous for his exploits as a war correspondent, for his passionate pursuit of big game, big fish, and the thrills of the bull ring.

Then there were four wives among many other women Hemingway hunted and captured. He married Hadley Richardson at 22 (she was eight years older) and divorced her at 27; Pauline Pfeiffer lasted ten years or so; then came the brief and stormy marriage with Martha Gellhorn, best known because of the background of the Second World War which they competed to cover as journalists. Hemingway had a habit of picking out his next wife while still married; it was no different with his pursuit of Mary Welsh whom he met in May 1944 and married two years later, after getting a divorce from Gellhorn.

Mary Welsh lasted the longest — seventeen tumultuous and rocky years — and her endurance was rewarded with inheriting all of Hemingway’s literary and physical properties. As the official widow until her end in 1986, Mary was keeper of the flame that fed the Hemingway legend in which she herself played a supporting role.

Timothy Christian’s full-scale biography attempts to elevate Mary Welsh to leading lady with a detailed account of her life during her marriage to Hemingway and in the aftermath of his untimely death. Her early life in the Minnesota backwoods and the rise of her journalistic career are given short shrift. By page 7 Mary is already 28 years old, briefly married and divorced, when she decides to leave Chicago for London. There she makes a cold call to Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian-born press magnate, who first tries to seduce her but eventually arranges for her to be hired at The Daily Express, the largest circulation newspaper in his empire. There she gradually works her way up from the women’s pages to covering politics and foreign affairs. She also marries her second husband, the Australian journalist Noel Moncks.

Mary’s career takes off with the start of the Second World War. She was an American already on the spot, reporting for Time-Life from Paris and London, covering the major events and players. She meets many interesting people and a few who excite her. The war frequently separates her from Noel but absence does not make her heart fonder. Among several lovers she finds the young American writer Irwin Shaw particularly appealing, but Shaw does not want a serious relationship.

Ernest Hemingway arrives in London in May 1944, already a global celebrity, to cover the planned invasion of France for Collier’s magazine, leaving Martha Gellhorn to make her own way to Europe. Unable to tolerate such an independent woman, he falls at once for Mary, another adventurous reporter, who admires his writings but is not impressed by the man. Hemingway wears her down and they tie the knot in Cuba in 1946.

A few months later, while travelling in the wilds of Wyoming, Mary suffers a life-threatening miscarriage, and is only saved by her husband improvising a transfusion of his own blood, after the attending doctor had given up on her. Christian picks this dramatic episode as the prologue to his biography, and also to explain the special bond that made this final marriage survive the next fifteen years of relentless adventures, accidents, abuse, alcoholism, and finally mental and physical decline.

Feeling trapped, Mary often contemplates walking out and issues ultimatums which amount to getting her husband’s permission to leave. That never comes, and she is liberated only by Hemingway’s death when her loyalty and endurance are rewarded by inheriting the entire estate of literary and real properties, scattered from Cuba to Key West, from New York to Ketchum, Idaho.

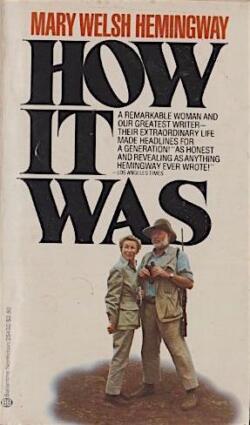

But she is not really free, because for the rest of her life Mary Welsh works tirelessly to conserve the Hemingway legacy: editing, publishing and promoting her husband’s posthumous works, guiding or fighting biographers and scholars, while coping with the families of Hemingway’s children whom their father mistreated, alienated or disinherited.

How capable she was shines through an episode when she managed to rescue crates of valuable paintings and invaluable Hemingway papers by negotiating between the two antagonists of the Cuban missile crisis. First Mary turned to her wartime colleague, Bill Walton, who was then working at the White House, to get President Kennedy’s permission for her to return to Cuba, where she and Ernest had spent their happiest years. Fidel Castro’s new regime was in the process of expropriating all property owned by Americans, but Mary made a personal deal with Castro to take what she wanted in exchange for donating the Finca Vigia to the Cuban people in memory of her husband’s admiration for them.

Lookout Farm, as the Finca was nicknamed, survives as a museum and place of pilgrimage, preserving Hemingway’s happy association with Cuba. Later, Mary showed her gratitude by choosing, from among several vying institutions, to deposit most of the rescued Hemingway papers at the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library.

The book is valuable for presenting in chronological detail a complex web of personal relationships and historical events that span much of the 20th century. The author has assembled a formidable compendium of sources, with extended quotations from Hemingway biographers, relatives and friends, all diligently noted in fifty pages of endnotes. However, the sheer amount of material gathered through years of research is overwhelming and, by its very nature, contradictory. Everybody who came into contact with Mary Welsh and her third husband experienced them differently and recorded their memories with their own motives. We look to the biographer’s craft to help us determine what is likely to have happened, who is to be believed and to separate opinions from facts.

The author, a distinguished law professor from the University of Alberta now retired to Vancouver Island, is eminently qualified to argue such distinctions; indeed, much of the book reads like material for a legal brief. His training serves him admirably when discussing copyright, wills or clarifying the rights of children to inherit, but more often it comes at the expense of developing a narrative and letting it flow. Page after page is filled with facts and quotations extracted from diaries, letters, interviews and published sources. Important characters, like Bill Walton, appear in passing and without context, mixed in with the names of others who turn out to be insignificant.

There is the rich American couple who hosted the Hemingways for six months of 1959 at La Consula, their spacious villa near Malaga. It was here that Hemingway, in declining health, struggled with updating his 1930s book Death in the Afternoon and with writing a long article about bullfighting for Life magazine. It was where Mary organized her husband’s elaborate 60th birthday celebration with thirty friends flying in, and where Hemingway’s abuse of Mary was open for all to witness.

Annie and Bill Davis who allowed their villa and lives to be taken over by Hemingway’s entourage are mentioned just by name on page 123 and nothing more is said until page 256 when Hemingway ‘arranged to stay with his friend Bill Davis.’ We never learn who these accommodating hosts really are. For that I had to turn to the 2016 book by Tony Castro, Looking for Hemingway: Spain, the Bullfights, and a Final Rite of Passage, which has an entire chapter titled “Who Was Bill Davis?” Curiously, that book is missing from Timothy Christian’s extensive bibliography, along with any reference to the writings and milieu of the British writer Gerald Brenan, who was a close neighbour and actually found La Consula for Annie and Bill Davis. Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy’s biography of Gerald Brenan gives a concise sketch of Bill Davis’s sycophantic relationship to Hemingway and other writers, and provides the wider context of their social scene in Spain.

(Here I must disclose my own interest in this Spanish episode. I first learned about Annie and Bill Davis through their son Teo, who supplied some of the information for Tony Castro’s book, and became a friend of mine in Los Angeles. He was in and out of rehab and once offered to sell me ‘Hemingway’s old typewriter’ as a decoration for my bookshop window in Pasadena when his need for drugs became acute. I visited La Consula, which had become a cooking school, two years after Teo’s death.)

But it is not the omissions that will burden the general reader. On the contrary, there is an overabundance of sources and references. Even the most experienced writers can use a hands-on editor, now becoming rare in publishing. (Hemingway had one of the best in Maxwell Perkins at Scribner’s). There also used to be copy editors who checked or queried facts. They might have caught that Lord Beaverbrook’s real name was Max Aitken, not Max Atkin (who was an Australian soccer player), or that Letitia Baldridge was Jacqueline Kennedy’s social secretary and not the President’s.

In a chapter devoted to the posthumous publication of A Moveable Feast, which Mary Welsh edited, we find her debating her publisher and other advisers over removing redundancies in Hemingway’s unfinished manuscript. The author, while faithfully chronicling the various sides and arguments, seems unaware of his own redundant repetitions. Or the irony of dealing with a writer whose style is most famous for what he left out.

*

Peter Hay is a former editor of Talonbooks and the author of several non-fiction books. He now lives in Summerland, British Columbia. Editor’s note: Peter Hay has also reviewed books by Joe Gold and Robert Krell for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1679 Mary Welsh’s inheritance”

I feel that every man’s real dream of life was or is to be like Ernest Hemingway. No one can say he wasn’t interesting & adventuring. No one can mutter that he didn’t have enough love & sex in his life. It can’t be said that he was unpopular. Plus, no one can say he lead a dull life.

Indeed, a pure diamond review of Christian’s biography of Mary Welsh Hemingway—so much packed into the biography and review. I have tended to be keen and more curious about Hemingway’s 1st wife, Hadley Richardson, given their years together in Paris-Austria and ski adventures (an avocation of mine). The final chapter in A MOVEABLE FEAST but a teaser of Hemingway and his ski bum ways with Hadley, the 1st reflection in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” not to miss, “Cross-Country Snow” and “An Alpine Idyll” evocative charmers, Hadley, alas, fading as Hemingway takes to the alpine with friends in Switzerland and Austria on his boards. But, THE PARIS WIFE by Paula McLain is worthy of the reading journey, Hadley front and centre. Perhaps McLain and Christian should be read together for the young Hemingway and the autumn season Hemingway.

montani semper liberi

Ron Dart