1580 Because matters

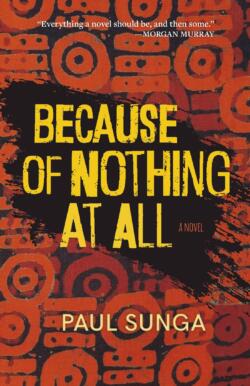

Because of Nothing at All

by Paul Sunga

Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2022

$24.95 / 9781773102467

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

On first glance, I thought that the title of Paul Sunga’s new novel, Because of Nothing at All, seemed awkward, but I soon changed my mind. Because the moment you start reading, it’s clear that ‘because’ matters — to the author, as it should to all of us. ‘Because’ attempts to explain. ‘Because’ attempts to justify. ‘Because’ even attempts to dismiss or disenable. Sorting out ‘because’ is definitely what a book sometimes attempts to do, often arrestingly, as here. And as this novel demonstrates, ‘because’ can do even more. So can ‘Nothing,’ and it’s in that paradox that Paul Sunga’s fascinating, absorbing, seriously disturbing book begins.

On first glance, I thought that the title of Paul Sunga’s new novel, Because of Nothing at All, seemed awkward, but I soon changed my mind. Because the moment you start reading, it’s clear that ‘because’ matters — to the author, as it should to all of us. ‘Because’ attempts to explain. ‘Because’ attempts to justify. ‘Because’ even attempts to dismiss or disenable. Sorting out ‘because’ is definitely what a book sometimes attempts to do, often arrestingly, as here. And as this novel demonstrates, ‘because’ can do even more. So can ‘Nothing,’ and it’s in that paradox that Paul Sunga’s fascinating, absorbing, seriously disturbing book begins.

To write Because of Nothing at All, Sunga draws on his own experience as a public health worker in Africa and Asia. As a medical studies teacher (currently at Langara College in Vancouver), he also brings the particularities of his medical knowledge to his subject. Set primarily in Turkana, the desert county of northwestern Kenya, on the Ethiopia/ South Sudan/ Uganda border (there are scenes in Canada and the US as well), his novel follows several lives that radically change over the course of even a few weeks in 2016. It suggests several reasons to explain why the events and actions here unfold as they do, and it reveals itself to be a powerful, articulate, carefully modulated representation not only of one corner of Kenya but also of the ways in which contemporary lives are repeatedly shaped by the workings of power.

Distinguishing between those who wield power and those who have no power to wield — an imbalance that changes several times over the course of the narrative — Sunga’s novel makes clear that the markers of power range from bureaucracy to violence, from title to food, from names to naming, from Western medicine to local knowledge — and that everywhere power involves money. ‘It is nothing,’ says one character to many another; then ‘you have nothing’; then ‘you are nothing.’ This slide from observation to assumption to judgment to (in)attention — it happens between adults and children, between men and women, among siblings, within groups and gangs and institutions — is consequential (hence the resonant title). Because, because. The novel asks its readers to grapple with these consequences, and in more than a merely casual way to understand that everyone is involved.

Serious issues. And a serious look at people, wherever they may happen to be.

Stylistically, the narrative is something of a tour-de-force, weaving its way through various local idioms, speech sounds, and conventional class markers, and evoking the rhythms of territorial speech, both Turkana/ Nairobi (i.e., roughly speaking, ‘rural/ urban’) and the border-blur of ‘Canadian/ American.’ Some other patterns appear along the way, a way that proves to be at once both intricate and (given its analysis of causality) seemingly inevitable. At least in the present. But it’s by no means a raw communiqué or a schoolbook treatise. Because the novel manages to combine the narrative strategies of a thriller with the documentary detail of its ‘social realism,’ it engages at the level of action as well as through its social observations; it pulls readers along, eager to know what happens next, eager to find what (and if) the ‘nothing’ of the title can be made to mean. The answer is: Yes it can. But often uncomfortably. Controlling that tension is one of Sunga’s many strengths.

The novel begins (formally) with a press release in 2016 (concerning an abduction in Kenya), a document that disappears into the maw of bureaucracy (from the start, readers’ expectations of action are already being reshaped: at a time when action is necessary, delay and inaction too often take precedence, as though, because ‘nothing’ can be done, nothing is done).

The novel then begins a second time, tracking events in a Kenyan child welfare centre which portrays details of starvation, abuse, occasional tenderness, and overall corruption: events that explain another ‘because.’

Then it begins again. There are many beginnings, as though the promise of a new possibility is key to understanding what keeps going wrong.

As the narrative gathers speed, the central chapters focus on three characters as they head into the desert in April 2016 and become the targets of an economic (therefore political) kidnapping: Kestner, a Canadian medical doctor in Kenya who’s been tasked with writing another review, this one concerning a refugee health program; Mason-Tremblay, a development officer with the Canadian government’s Global Affairs team; and Mihret, an Ethiopian national, a woman whose athleticism and fluency in Swahili serve her well, up to a point. Each of them has a backstory (generally in the West), though Mihret’s is left deliberately unclear (‘knowing all’ is not a prerequisite to empathy). In each we discover the flawed reasons that have led them to this part of Africa, flaws that will have an impact on how (and whether) they can survive. Readers also follow their driver Salim Mohammed; and a former child from the failing welfare school, whom the bloated schoolmaster has arbitrarily named Money; and several others whose knowledge — of Islam, languages, the prophets’ poetry, the roads, the parched county, piracy, the psychology of religion and violence, and the forces of power and exchange — will impact everyone when the three foreigners are abducted, traded, put up for remuneration, and otherwise dealt with.

The novel develops mainly through the visceral details of the abduction narrative, but I’m not in this review going to reveal what happens except to say that this is no drawing-room whodunit but a serious look at current events. I will, however, draw attention to the way Sunga structures his chapters so that the events emphasize how much everyone’s actions are in one way or another tied up with ‘The Imperatives of Money,’ ‘Imperfections in the Market,’ ‘The Movement of Capital Assets,’ ‘Costs and Benefits,’ and so on. This strategy gives depth to the novel as a whole; small action in the microeconomy parallel those in the macroeconomy. Further, the economic underpinnings reinforce the ongoing portrait of the central (and in some degree representative) African figure ‘Money Manyu,’ whose nascent desire to inhabit his name is constantly under threat. The differences between an expectation of payment and the reality of liquid income — as between medical knowledge and practical wisdom, or between the desire for self-sufficiency and the pressures of dependence — illuminate the novel’s concern to understand causality (again the title resonates) and its analysis both of personal failure and (potential) social collapse.

Causality matters, but the novel makes clear that identifying a cause does not itself resolve it: or not yet. This novel takes notice of some of the people, actions, ideas that others often dismiss as ‘nothing’; it attaches worth to people, actions, ideas, even when they’re in some way flawed; it exposes the way many in power gloss over people, actions, ideas because they say they’re dealing with ‘nothing in particular,’ and it affirms that the particular is always important and must be attended to This novel may horrify you; it will engross you; it may even change the way you think about the world.

*

William New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. New’s most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (Rock’s Mills Press, 2021), reviewed by Gary Geddes. Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Emily St. John Mandel, Tamas Dobozy, Rhonda Waterfall, Leah Ranada, John MacLachlan Gray, and Bill Stenson for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1580 Because matters”