1557 Better than real life

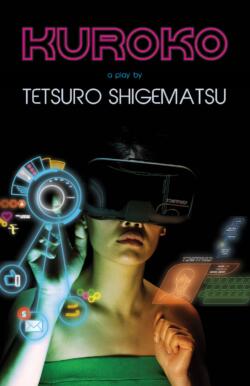

Kuroko

a play by Tetsuro Shigematsu

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2020

$18.95 / 9781772012699

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

I wouldn’t liken making fun of Tolstoy to a sport, but it is, surely, a reliable source of amusement, which likely sounds disrespectful; therein lies the amusement. All that to say, when Tolstoy wrote “All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” did he have any inkling that he had written a catchy, if dicey aphorism? On some level, Tolstoy is romanticizing the ostensible uniqueness of unhappiness; of course happy families are homogenous, orthodox, and reliably boring folks who eat meals together without the crude assistance of a television; of course an unhappy family has transcendent angst and individual traumas of such dazzling complexity and it is this kind of fetishization of unhappiness in its supposed myriad forms that corroborate the persistent idea that sad artist = good art. Tolstoy’s aphorism is, perhaps a little too neat; however, in Tetsuro Shigematsu’s play, Kuroko (“child of darkness”), we certainly do get an interesting unhappy family.

I wouldn’t liken making fun of Tolstoy to a sport, but it is, surely, a reliable source of amusement, which likely sounds disrespectful; therein lies the amusement. All that to say, when Tolstoy wrote “All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” did he have any inkling that he had written a catchy, if dicey aphorism? On some level, Tolstoy is romanticizing the ostensible uniqueness of unhappiness; of course happy families are homogenous, orthodox, and reliably boring folks who eat meals together without the crude assistance of a television; of course an unhappy family has transcendent angst and individual traumas of such dazzling complexity and it is this kind of fetishization of unhappiness in its supposed myriad forms that corroborate the persistent idea that sad artist = good art. Tolstoy’s aphorism is, perhaps a little too neat; however, in Tetsuro Shigematsu’s play, Kuroko (“child of darkness”), we certainly do get an interesting unhappy family.

In the first scene, we immediately get a hook: a business card that pronounces “Better than real life.” (Whether that’s impressive, or a relatively easy feat, I’ll l leave to you). What is being sold? Actors for hire. Hiroshi, who lost his job six months ago, is rather unoriginally planning to commit suicide. Before he does, though, he wants to ensure that his daughter, Maya, is no longer a hikikomori—which, according to Wikipedia, translates as “pulling inward” or “being confined”; picture someone so ill at ease with the world that most of their time is spent indoors, probably in their bedroom, possibly for years—but a functioning member of a society that, you know, sometimes eats with other people. Tellingly, Hiroshi believes that losing his job—which his wife, Naomi, has no idea about—is worse than cancer.

Ms. Asada, the owner of the rental family agency, guesses what Hiroshi wants for his daughter: “A girlfriend to go shopping with? A boyfriend to see the cherry blossoms? Grandparents? A new mom? … How about an older sister?” Despite the gamut of possibilities in her rental family agency, Ms. Asada refuses to accept Hiroshi as a client. She believes hikikomori are the symptom of the problem; that is to say, Ms. Asada suggests that the people around Maya—namely, Hiroshi and his wife, Naomi—explain Maya being a hikikomori better than Maya herself. Reluctantly, Ms. Asada gives Hiroshi another contact that may be able to help. Ms. Asada, for the first but not last time, says to Hiroshi: “ … it’s okay to be scared. It means something incredible is about to happen.”

Another component to this unhappy family? Ichiro, the firstborn son, disappeared in Jukai, or “Suicide Forest” when he was fifteen. Hiroshi steadfastly believes Ichiro is missing, not dead.

Ms. Asada’s contact turns out to be Kenzo, who is hired to befriend Maya in a virtual reality game, providing a mode of socialization that, while not necessarily fulfilling the conventional notion of Real Life, nevertheless offers more socialization than Maya’s engaged in for years. This isn’t Bridgerton, but we, unlike Kenzo and Maya, have the foresight to know that pretending to befriend (or romance) someone generally leads to the pretence lapsing into tangly, real feelings. It’s a trope, and one that’s persisted because when it’s done right, the expectation fulfillment is delightful.

The dialogue between the two initially consists of strategy and insults, but gives way to more personalized insults, like Maya suggesting Kenzo will remain a virgin for life, which either means Maya is guessing Kenzo is a virgin, based on his vibe, or they previously discussed it; either way, it’s personal. Kenzo, hired to befriend Maya, gets her to name three things she loves and three things she hates. With no knowledge of the duplicity present from the onset of their friendship, she names three dislikes: “Natto. Nosey neighbours. People who aren’t who they say they are.” Oh, delicious, delicious, dramatic irony. Kenzo then encourages Maya to say, enthusiastically and disingenuously, “I love natto! Gooey, sticky, stinky natto.” When it’s Kenzo’s turn to name three things he dislikes, he says “Discrimination, bullies, daikon.” Maya responds, amusingly: “So you despise social injustice and fibre. Got it.” Kenzo then encourages Maya to ask him anything, and it is with, apparently no hesitation, that she asks: “Have you ever fantasized about me?” Kenzo has, and asks Maya the same question. She, too, says yes. In other words: Hiroshi’s plan is working. Maybe even a little too well.

Of Jukai, or “Suicide Forest,” Kenzo observes that “I don’t know if Jukai is the most haunted forest in all of Japan, but it definitely has the most trash. Weird how people’s last meal ends up being junk food.” In scene 26, “Konbini,” there is a visual callback to Kenzo’s observation, involving Pocky. Throughout, Shigematsu is very good at incorporating satisfying callbacks; for instance, “It means something incredible is about to happen” is reiterated by the original speaker, Ms. Asada, but also something Hiroshi echoes, much later.

Kuroko is an excellent play that forces me to reconsider my resistance to saying that I was “grabbed” by something engrossing. I have almost no complaints whatsoever, except that, perhaps, Naomi is not as developed as the other characters, but even she gets an amusingly awkward moment upon meeting Kenzo that adds nuanced levity to her role: “I’ll have you know that I’m not like other Japanese. I happen to think that your people are, are… very good-looking.” Shigematsu’s dialogue is perfectly calibrated: there’s the refusal to be lumped in with stereotypical Japanese people; there’s the double pause with the comma and the ellipsis and then, the actual compliment itself that is meant to scaffold her self-description as “not like other Japanese.” The effect of all this awkwardness, therein, is hilarity.

Kuroko is funny, never boring, full of heart, and, admittedly, perhaps a confirmation of Tolstoy’s irksome aphorism, up to a point. I’m curious what Tolstoy would say about an unhappy family that migrates closer to a happy family — do they lose their heterodoxy and idiosyncrasy? Shigematsu manages to give us an ending that is neither sickly nor sentimental, but exactly right.

I once knew a guy who said American Beauty was his favourite film because, according to him, everyone could relate to something. I’m not sure that’s true, but I like the idea. You don’t need to be familiar with the hikikomori phenomenon or Japanese culture or virtual reality games to enjoy this play; really, my only remorse is that I did not get to see this play live for, just on the page, it is already alive.

*

Originally from East Vancouver, Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and a pianist of dubious merit living in Toronto. She is currently an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has recently reviewed books by Katie Welch, Megan Gail Coles, Ayesha Chaudhry, Gillian Wigmore, Meichi Ng, and Alex Leslie.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1557 Better than real life”