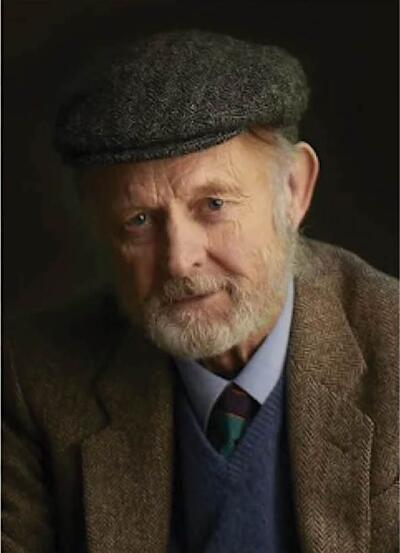

1497 Tribute to Julian Wake

A tribute to Julian Wake

by Richard Mackie and others

*

It’s a pleasure to provide this tribute to Julian Wake, a friend to me and many others between his arrival in BC in 1966 and his death on January 16, 2022. In recent years Julian embarked on a late career as a book reviewer for the The British Columbia Review. He reviewed memoirs by Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe and John Wilson and a biography by Robert Hutton, and at the time of his unexpected death of a long-standing heart condition he was keen to keep reviewing. I keep finding books where I stop and think, “I’ll bet Julian would like that…”

I’ve included several short memories of Julian below, starting with my own. Anyone else who knew Julian is welcome to send me their own memories or photos, and I will add them, or you can leave a comment at the end of this post. An obituary has appeared in the Gulf Islands Driftwood. — Richard Mackie, editor, The BC Review

*

Richard Mackie: I met Julian Wake in Victoria in 1989 when I was four years into a PhD in history at UBC. Julian had recently, on the collapse of his marriage, moved from Kaslo to Victoria, where he was working as a taxi driver and delivering the alternative newspaper Common Ground to the organic food stores and bookstores that carried it. He stayed in a downtown flat with an old friend from UBC, played cricket in Beacon Hill Park, and attended Christ Church Cathedral. Once we attended a service together, and as soon as we got out of the massive doors onto Quadra Street, Julian turned to me and said, “I’m parched! Let’s go and find a pub.”

Julian had been at Eton, a major public school in England. He said there are at least two Old Etonians in every major city in the world: one is the British ambassador and the other is in jail.

Soon he got a job with Victoria anthropologist and land claims researcher, John Pritchard, and from there he found his way back into a professional life and important work with First Nations, government, and corporate sectors, which are touched on in the memoirs below.

Memory can be a tricky customer, but this is what I remember of his early career: after Eton, he spent a year teaching in Jamaica, but his ambition was to be an estate manager — a land steward — on the properties of his family or friends in the UK, and with this in mind he came to BC in 1966, when he was 18, to study forestry at UBC. His father (Roger Wake, 1918-1988) provided an introduction to lumberman H.R. MacMillan, who offered him a guest room in his house in Shaughnessy. Julian spent his first summer in BC playing tennis at the MacMillan mansion.

He then went to UBC where, he told me, he “discovered LSD, sex, and Karl Marx” — though I can’t guarantee that that is the right order. His UBC friends in the late 1960s included future psychologist Gabor Maté, and the writer Stan Persky, who recalled that:

We were students together at UBC in the late 1960s, and Julian was part of our gang, which operated under the rubric of “Human Government,” the New Left humanities students who resisted the blue-blazer-wearing posh young Liberals who ran student affairs at the university (email from Stan Persky, June 17, 2022)

At this time of his life Julian had a lot of tradition to resist, to push back against and get in perspective. He came from an established landed gentry family, the Wake Baronetcy of Clevedon in the County of Somerset. The Wakes claim descent from Hereward the Wake, an Anglo-Saxon nobleman (1035-1072 AD) who led a revolt against the Norman invaders of 1066. Julian’s ancestors and relations ramified through British history and society and back into the aristocracy. He once pointed to a mountain in the Kootenays that was named after a relation of his, a mid nineteenth-century English statesman. Julian was the grandson of the 13th Wake baronet; his uncle Sir Hereward Wake was the 14th baronet; his first cousin Sir Hereward Charles Wake (born 1952) is the 15th baronet. As the “younger son of a younger son,” Julian had little hope of inheriting the title or the family seat, Courteenhall House in Northamptonshire, and like his father and everyone else in the family he had to find a job (City, clerical, army, professional) of some sort. His father was on the board of the London merchant bank, Kleinwort Benson, to which there was a family connection.

Julian prospered at UBC; he dropped forestry and did his BA (1970) and his MA (1973) in anthropology; his thesis, called simply “The Sanyasi,” was supervised by Dr. Ken Burridge (Kenelm Oswald Lancelot Burridge, 1922-2019), who became a lifelong friend. The thesis begins:

After researching all the data I could find pertinent to the Indian sanyasi, it became apparent that the principal question raised by this research is being posed again in a contemporary form in the conflict between two schools of the “underground” press. On the one hand is the position of the effervescent counter-culture, emphasizing spontaneous personal self-expression and a kind of self-determination that ignores as much as possible its connections with the society from which it is a peripheral offshoot. On the other is the more radical organized stance which argues that the former’s position is self-deceiving, summing it up by saying that “personal solutions are no solutions”, (see The Grape, vol. II, no. 12). To the latter, sanyasis are anathema, particularly those (the ‘gurus’) who ask others to adopt their personal solutions to the problem of social freedom as their own. This thesis accepts the latter’s stance and undertakes to demonstrate its validity from a sociological point-of-view.

This counterculture venture into Indian philosophy and religion was a far cry from the Wake family bailiwick — far from the deep traditions of rural England that had sustained the Wakes for a millennium.

Julian mentioned an incident from 1970 that, to him, summarized the whole Vietnam War era in BC, when thousands of American war resisters came here. As I recalled it, an American war resister took his younger brother, who was visiting from the US, on a hike when he intentionally dropped a large slab of rock on his brother’s leg and broke it. He then feigned that the injury was caused by a fall. This was to give the brother a reason not to return to the US and face the draft. I contacted Julian’s friend, who even after many years wishes to remain anonymous, and asked him to verify the story. His brother, he said, was already in the US Army when he came to BC on leave, but “he was to be sent to Vietnam as a scout, a high mortality position.” He recalled the incident:

We decided to execute our vague plan in Hope, under the guise of a fishing trip. Mission Hope. As the anesthesiologist, I was to make sure **** swallowed the correct amount of vodka. Enjoyable for both of us. My other brother **** stayed straight, working up the nerve to drop the rock. After a few bottles of vodka, the patient and anesthesiologist were primed. We’d chosen a spot on a river near the hospital. We put ****’s leg over a small log and scooped sand from underneath his calf. I held his hands as **** dropped a rather large rock on his shin. It was dusk. The sound was like a sizeable branch snapping in two. *** and I wanted to rush him to the hospital, but **** , who has a very high pain tolerance (unlike the anesthesiologist) insisted on waiting a few minutes. Like a drunk, he figured it would appear more realistic. At the emerge, while the doc was cutting away his pants, **** winced — but then he winked at me.

Around this time Julian moved to the north end of Kootenay Lake where, he told me, he lived in a commune at Johnsons Landing. His job was to keep the pot simmering during the winters. He went up into the mountains with his shotgun for game birds, and his rifle for deer, for the communal pot and he was proud that stew or soup was always available. The same large pot was rarely taken off the stove for an entire winter. For Julian, used to the English rural pursuits of hunting, shooting, and fishing, this was a familiar and useful engagement with the land. He told me that he followed creeks and game trails far up into the Purcell Mountains.

In 1991 I met Julian in New Denver when I was writing the first draft of my PhD dissertation at the Harris family’s Bosun Ranch. We drove over to Kaslo in Julian’s car to meet his children, Rowena (born 1978) and Callum (born 1983) while their mother Josie (née Alata) was at work. He then took me to see the family house he had built. He fell into a deep and poignant silence while we drove through the life he had left behind. We looked at his house from the road, and he pointed out what had been his extensive vegetable garden. We drove past places where he used to work, including a sawmill at Argenta.

In January 2007, after I sent him an article of mine, “The Bushrat Inventory” BC Studies 131 (Autumn 2001), Julian reflected in an email on his years at Kootenay Lake:

A seminal influence on me was Jim McNicol who trapped all his life (except four years as a tail gunner in Lancasters: that is another story.) There was much respect for packrats but their sudden noisiness can be alarming, as you know. The only way to catch them was to dangle an apple from a string just out of jumping range above a covered number “ought” leghold. They would recklessly leap up and fall back onto the trap. Jim also introduced me to Zambuk which is a panacea for minor afflictions and which I carry to this day.

We went our separate ways but somehow managed to see each other about once a year, and Julian visited me in Cowichan Bay and Vancouver. In 2007, I sent Julian a copy of an article by Jo Jones in Okanagan History — “Mr. Byam’s Bones,” (Vol 63, 1999: pp. 126-133). Briefly, it concerns the remains of an unknown man found in 1894 nine miles up the North Fork of Cherry Creek between Vernon and the Arrow Lakes. All that was left was a human skeleton, some tattered clothing, and a small and weathered notebook. Alice Parke, the resourceful wife of the provincial constable in Vernon, was determined to identify the man. The notebook read in part: “Had to kill Willie, the dog,” “Found a few berries,” “Weaker & weaker,” “Ate last of dog — the end must come soon — but God is good — something may turn up,” “Love to Agnes,” “Visions of food are constantly before us,” “Weaker,” and finally, “Cold.”

Alice Parke could make out only two clues in the rotten notebook to the man’s origin or family: “Miss Agnes B…” and “C-ck… Sussex Eng…” She consulted a gazetteer and decided that the only place in Sussex with a name that fitted was a village called Cuckfield, and she persuaded the Vernon postmaster to write a letter of inquiry about “Miss Agnes B” to the postmaster there. Weeks later Miss Agnes Byam of Woodlands, Cuckfield (near Hayward’s Heath), wrote back to identify the missing man as her brother, Arthur Merrick Byam, the third son of General Byam of the 18th Hussars, and of their mother Elizabeth Augusta, daughter of Sir Grenville Temple, Bart. Arthur Byam had come to BC in 1861 as a gold miner. He was about 55 years old at his death. Miss Byam reported that he liked to walk with his dog between his network of friends on the coast and Interior of BC — mainly magistrates, gold commissioners, government agents — when he must have lost his way. He had been back to England, Miss Byam wrote, but he complained that “people lived in bandboxes,” and he much preferred his new life in Canada.

Julian was intrigued by the story of Byam, who had come from a similar background in England. He wrote to me as follows:

Richard, There is something peculiarly pathetic about the story of Arthur Byam and the way this country swallows solitary people and yet may rescue them from pointless anonymity. Maybe Russia and large deserts do the same.

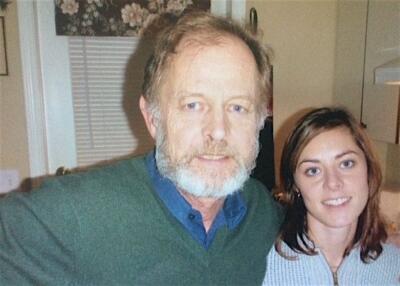

I hope this tribute to Julian Wake will help save him from any pointless anonymity that might befall his memory and contribution. I am grateful to Julian’s own network of friends on coast and Interior — and further afield — who have contributed their memories below, and to his children Rowena and Callum Wake for supporting this venture — Richard Mackie.

*

Caroline Kennard.

Julian. I first met Julian at 55 Speed House, The Barbican, London, England.

I was sharing the flat with Jane, Julian’s dear sister and his father, Roger. His brother William was there quite a bit. William sat on the sofa wearing raspberry-coloured crushed velvet trousers and not doing much. Oh yes, and Fourpence the dog.

Julian was in his early twenties and on a visit back from Nepal. He was living and studying there. I remember Jane had to pick up and make sure he got the fancy invitation to The Royal wedding of Prince Birendra in Nepal. Julian had been at school with The Prince. Anyway, Julian arrived at 55 Speed house with his head shaved and he was skinny. Actually scruffy and scrawny.

The next time I remember him was at the communal house on Laburnum Street in Kitsilano, Vancouver. It was the early 1970s. Jane and I had just arrived from our bus tour of the United States of America. We had luggage. Frocks and smart outfits. Julian said he had put straw down for us in the basement. And indeed he had. We were sitting on the floor around a large wooden spool used to eat off. Julian had a little smile when he said, raising one hand and then the other, “you eat with your right hand and wipe your bum with the left.” And he was helpful: he told me to get on a contraceptive pill as I was driving to the Yukon with a man. I was aghast and did what he said.

What I want to talk about is Julian as a countryman. My belief is that those of us were lucky who grew up in the English countryside at a time when childhood was less structured. We were freer to roam and explore country life. I didn’t know Julian when the family lived in Northumberland, so I am surmising. I do know that Roger, his dad, loved his garden and country pursuits. I remember Roger in his garden at Welham. He enjoyed showing us his old-fashioned roses with their fabulous unforgettable smell.

And his mother Olwyn’s garden at White Roding was truly stunning. Her surroundings were so beautiful. Olwyn knew about country things. She made delicious Elderflower sorbet, pot pouri, and she grew gorgeous flowers. I think Julian’s favourite flower was the Siberian Squill, but I could be wrong. Olwyn was a superb cook and used vegetables from her garden and what she gathered from the countryside.

I think it was from Olwyn and perhaps scripture classes at school that led Julian to take pleasure in Anglican Church services and the liturgy.

I know Julian honed and continued his love and understanding of the land when he was in Johnson’s Landing and later In Haida Gwaii. He was a very good fisherman. I remember watching him fly-fishing on the Quatsino River, out of Port Hardy, and he did it superbly. Another time when he was on the boat with Alison and me, he caught a very fine Coho salmon. Alison and I had fished off that boat for years and caught absolutely nothing. We ate the salmon at Herman and Martha’s house on Pender Island.

Julian was very good at games, more often called sports. He played great tennis with a racquet that ought to have been in a museum. I am told he played The Wall Game at Eton, an ancient, unknown to most people, rough tough skilled pursuit which Julian excelled at. And I bet they wore weird uniforms too.

I have to admit I loved watching him play cricket in Victoria with The Albions. His whites still fitted from school and were a bit yellowed.

He knew a lot about wild life in the surrounding countryside. He could point out a variety of ducks. The difference between a bufflehead and a barrows golden eye. And the widgeon, plus others like a harlequin, and of course the lesser scaup. And he didn’t make it up like some of us do.

I remember him pointing out to me the holes in a tree made by a pileated woodpecker. They were large. One of our favourite birds is the semi-palpated plover. Or is it the killdeer? Julian would know. When he was so ill he took great pleasure from his bird table and he was delighted to see the Californian quail in his garden on Salt Spring Island. He was so pleased that he had got a Nootka rose to grow. And then those huge, prized, wormy cabbages he grew, which I had to cut up every day for lunch.

Julian and I had not got on well for some time. Perhaps it was his illness, but I saw less of the infamous Wake charm and he got quite irascible, incorrigible and a few other bulls. It was not me, of course!

But there was one thing we were in complete and total agreement about. And that is that Jose and he have wonderful, beautiful, handsome, smart, funny, and dear children, Rowena and Callum. My mother said Jose was very beautiful. She had opinions and liked to make pronouncements. Jose and Julian have brought stars into the world.

Julian once wrote to me, after a period of non-speaking, that his life was less colourful without me around. Well, Julian, mine feels pretty bleak right now without you. Even to grumble about you. I think of you when I walk in the forest or on the beach, and I see birds I want to tell you about. My Hemedi, Hutch, liked Julian very much. Julian had a special rapport with First Nations. As they say on this Rez, we must hold on to one another — Caroline Kennard, Campbell River and Tsakis (Fort Rupert).

*

Alan Dennis.

Dear Julian, We do go back a ways. My grandfather, a solicitor in Llangollen, was clerk of the court when your grandfather as JP and Lord Lieutenant of Denbighshire presided. They were also friends with the shared horror of the First World War. Their daughters, our mothers, were acquaintances and became friend when their children connected.

I don’t think we first met in about 1965 at the Old Rectory, your Mum’s home, because you were busy being a star at Eton. I did meet your sister Jane then and her friend Caroline before they came to Canada for finishing school.

I think we met downstairs at 2424 Ottawa Avenue, my Mum and Dad’s home in West Vancouver. You were busy at UBC moving from forestry to anthropology and through the politics of the time.

Some strong standout memories are of you speaking eloquently at the Advance Mattress about your thoughts and experience in Jamaica. Was that before or after I met you in Kathmandu where you were attending the Crown Prince’s wedding? He was a friend and classmate of yours at Eton.

Back in Vancouver, before you moved to the Kootenays and hitchhiked with a goat: I think the RCMP gave you a ride. You were the laird of Laburnum Street house, next to the Legion, with very transient tenants and lodgers. As laird you had the best corner bedroom with windows. We then moved to a grand old Dunbar house with a splendid garden and Greek landlord upstairs. We were evicted for various reasons that I have forgotten. It must be the only eviction party attended by Rolly Web in his Rolls Royce with my Mum and Dad. I think the landlord wanted to turn around the eviction order. What a laugh!

Why on earth (so to speak) we went out to Chilliwack to jump out of an aeroplane, I’ll never know. I think we found each successive jump more frightening than the first and soon gave up that pursuit.

All our family dropped into your Kootenays home over the years. The beautiful home you built. I have photos of baby and child Rowena. Thoughts are piling up: Haida Gwaii, Smithers … finally Salt Spring and your wee paradise home and garden.

You did take on some tough projects. Aboriginal Affairs Liaison officer for the BC Forest Service in Haida Gwaii was a tough one. Your allegiance, both social and political, was with the Haida. Couldn’t have been made easier by being married into a Haida clan. And then for a final career move to the even more difficult job on the gas pipeline.

I love your story of the meeting with the top management in a dreadful Calgary oil tower. You challenged the senior vice president, a younger woman with whom you had a difficult working relationship. She said, “Do you know you’re talking to senior management?” Your reply: “Do you know you’re talking to a senior?” You did well to survive that toxic environmental and political (First Nations) advocacy. Once again your true allegiance was to the First Nations you were liaising with.

Those were tough projects to prepare for retirement at your new home sanctuary, enjoyed for too short a time. Sad for me that my book Snow Nomad was published on 19 January 2022, three days after you died. I was worried about your high level critique, but you were also a participant and would have had some unique opinions — Alan Dennis.

*

Ron Smith.

I was deeply saddened to hear of Julian’s death. He and I reconnected last year in response to a review he had written for The BC Review of Lands of Lost Content by John Wilson, a Lantzville friend and neighbour of mine. Thanks, Richard, for providing me with Julian’s contact information; we had a brief email correspondence in which we discussed getting together sometime in the near future. Both of us were keen to re-unite but both of us were somewhat wary of travelling to each other, Julian before he had his heart surgery, me because of my stroke and recent bout of CHF (Editor’s note: see here and here for books by Ron and Pat Smith).

Julian and I talked eagerly about meeting in the new year, 2022. Pat wondered towards the end of January why we hadn’t heard from him. We were concerned for him but didn’t want to disturb him in recovery. What a shock, then, that we missed a chance to talk to an old friend, one we had last seen over fifty years ago.

In 1968 Julian moved into a house that four of us shared at 6th and Alma in Vancouver, now the site of an apartment building. My memory is a bit faulty on details but I think he had recently arrived from England and we had been introduced through other English neighbours. Julian fit in wonderfully. He was quiet, gentle and a lot of fun. Just before the term started we held a large party, 250 or so guests, one of whom was an old mate of Julian’s from Eton. It just so happened his friend had brought Pat to the party, the woman who was eventually to become my wife — mother of Nicole and Owen. Quite quickly Pat and I became a couple and decided to get married. Julian became a part of the process, proposing a little church in West Vancouver as the ideal place for the ceremony, St. Francis-in-the-Wood, in Caufield. The three of us visited the church one evening and the decision was made. We were married there in May of 1969. Julian gave us a little green lion as a wedding gift, which we still have and cherish.

To backtrack a little, by late April 1969, I had pretty much moved out of the house on 6th and was busy marking papers. I was also making plans to do graduate work in England, eventually either in Stoke or in Leeds. Leeds it would be. By the time we returned to Canada, Julian had moved on to the Kootenays. We shall remember Julian with great fondness and his role in our 53 years of marriage — Ron Smith.

*

Ruben Kaufman.

I met Julian when we were both 1st year M.A. program students in anthropology at UBC. After a while we ended up living in the same house. It was one of the well-known hippie houses in Vancouver.

We both independently chose Dr Kenelm Burridge as our supervisor. Dr Burridge occasionally invited me to lunch at the faculty club or his home. One day over lunch he said to me, “I don’t understand why I get all the renegades.” My answer was quick in coming: I told him that it was no doubt because he was so intellectually stimulating, that he typically asked questions about anthropological matters at a point where virtually all of the other professors would say “So, that’s it,” or “case closed,” or something else along those lines. These days he would be described as someone who thought outside the box.

So Julian was a renegade, a renegade from Eton who came to UBC, he recently told me, originally to study forestry, until he realized that what he had in mind was not what forestry at UBC was about. What he himself was about, I would say, was doing things, like building a house in the Kootenays, having a family, organizing a hippie version of a sun dance for the community at Argenta, and much more.

I eventually left BC and Julian and I were out of touch for decades, until a friend from the old Vancouver days reconnected us. I am very happy that I got to know him again, and it seems that in the few years we were friends the second time around we shared a lot in person or via email or phone. He was always very stimulating and a lot of his questions and comments were challenging, just as one would expect from a renegade who was drawn to the stimulating mind of a wonderful professor who thought outside the box.

Julian was very open and really wanted to get to know people. I remember his at times raunchy sense of humour and that he was a great dancer.

I sure have been missing Julian a lot, and look forward to reading comments from others who knew him to fill me in on what he was up to in the years we weren’t in touch, although I did get some of that from him — Ruben Kaufman.

*

Hope Norris.

I first met Julian in Argenta in the 1970s when he and Josi lived across the road on the land co-op and later when they lived at Johnsons Landing. He’d come to visit and soon be involved in a heated game of Risk on our large floor sized board.

We’ve always been friends, running into each other in the Kootenays, in Victoria, and when he was playing cricket in Vancouver and Salt Spring. Visiting through postcards, long phone calls about travel, books, our colourful friends and gardens. I would send along flower seeds for the garden of his new house. A dear friend for many years – now missed. — Hope Norris

Corky (Merry) White.

My story of Julian begins before I met him, with an invitation to a royal wedding in Nepal.

In the late 1960s, I lived here in Cambridge (Massachusetts) as a young mother, wife and graduate student, and my husband and I were approached to help settle in a new visiting undergraduate at Harvard from Nepal, the Crown Prince, in fact: Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev. We were asked if we could be a kind of homestay family for young Birendra. He wouldn’t live with us — he’d been given a room at Quincy House, but would we show him Cambridge, invite him to dinner. Well, surely yes.

Birendra was a sweet mild person — he’d become quite cosmopolitan in experience but still rather shy in demeanour. I remember a dinner with him and Narayan Prasad Shrestha, his companion-body-guard and rather a confident Gurkha who led conversation. Birendra had been to Eton, to Tokyo University, he’d been to a kibbutz in Israel, he’d travelled. He needed ordinary life, it seemed, but it was unclear what that would mean. And we weren’t all that ordinary.

My job, as it soon became clear, was to distract the bodyguard from Birendra, to give Birendra some breathing room, so that he might tool around our town in his burgundy Porsche and get to know people (women) on his own. I had to figure that all out. To give Narayan Prasad a room at Quincy House next to Birendra’s he had to have a title, a relationship to scholarship, and Harvard made him a Visiting Scholar in American Literature, specifically studying Moby Dick, a Herman Melville scholar. Thus, to make this at all likely, I would need to take him to lectures and to museums, taking long enough to give Birendra a copious afternoon of fun. And since I have no sense of direction at all, I would get conveniently lost.

When he left, we stayed in touch. An invitation came in the fall of 1969 to a wedding in Kathmandu in February of 1970. I’d never been anywhere on my own. From my forays into Victorian literature, I knew Kipling’s line “The wildest dreams of Kew are the facts of Kathmandu” — and I was dreaming wildly. I had no money for airfare or even the clothes required for a two-week wedding attended by heads of state and other elites.

I’d no skills at all but I paid my way through writing for the Atlantic Magazine, which took care of my airfare if I’d write a profile of Nepal’s geopolitical status.

The tiny plane arrived on the dusty airstrip to the tunes of a military brass band on the ground: who for, I wondered. It was, it turned out, for me, in my jeans and disheveled condition, lugging a duffel bag, me, a Royal Wedding Guest. And in the lodgings we were given as “Friends of Birendra,” an old palace-turned-hotel, were also the Etonian “Friends of Birendra” among them, Julian.

Julian’s pack of friends were interesting but we found that we shared a rebellious, questing frame of mind, and spent the many off-hours in the two-week-long wedding wandering away from the various entertainments laid on to pass the time between ceremonies that needed the astrologers’ go-ahead. I do remember Julian getting one of our drivers (we each had a car and driver, an unexpected perk) to go search out good hash, and once we took one of our drivers north along the newly built Friendship Highway, the Chinese-funded road between Lhasa and Kathmandu, to the Tibetan border. There, Julian, as an English person, could cross the border into Tibet, but I, as an American before Nixon’s visit to China, had to stay on the Nepal side. I was only a bit bitter, admiring the Himalayan landscape, sitting on a rock, and eventually he and the car came back, bearing an apologetic gift of a coral necklace.

Julian stayed on in Nepal, and we met again briefly at his home in England that summer. From then, 1970, to 2019, we were only sporadically in touch, Julian finishing degrees at UBC, I doing the same at Harvard, and I going on to teach — both of us in anthropology, Julian to work with the Haida and promote and defend their interests.

When the Annual Anthropology Meeting of 2019 was announced for Vancouver, I went to give a paper and thought, “isn’t there someone I know in Vancouver?” and found Julian, through his journal’s publisher who was kind enough to connect us. After fifty years, then, we did meet for a day of nonstop talking and walking, and when I saw him off on the boat to home I thought absolutely no time had passed since we’d first met and that surely, we’d meet again. And then it did not happen, though the letters flew back and forth til this past winter’s end. It’s those letters that filled in all the gaps, as the conversations begun fifty years back and continued in Vancouver cafes and dim sum restaurant could not tell all the stories. Julian was a wonderful storyteller, a wonderful writer and full of interestingly obscure literary references, often the same as mine. I read every book he ever told me to read. He told riveting tales of his life with family, with the Haida, with the Haida-as-family, and about his garden on the island and, for a time, tales of a dog companion. Always, stories of his children. His life was full of spirituality and a somewhat restless questing but also full of a sense of sufficiency; those together made our meetings and our messages into a kind of life lesson, for which I am profoundly grateful, as I profoundly miss him — Corky (Merry) White, Department of Anthropology, Boston University

*

Harley Rothstein.

Memories of Julian. Julian and I met in 1968, not long after he came to Vancouver to study at UBC. He and I became part of a wide circle of friends which included a number of anthropology students, like him, and a few history students, like me. This extended friendship circle also included several communal houses and its share of student activists. Some communal houses were friendly rivals such as Julian’s “First Avenue House” and my “Stephens Street House.”

Our favourite place to go for a drink after a full day of school was the Cecil pub at the north end of the Granville Bridge. (Many years later the Cecil became a strip club, but in our day it was just a place to drink beer.) One night, a large group of us were sitting around a table at the Cecil and I found myself sitting next to Julian, who I didn’t know very well. In conversation, we found that we had a lot of things in common, and we continued talking for what seemed like hours. Have you ever been in a situation where you’re talking intensely to someone and after a while it feels like there are just the two of you in the room? That’s how I felt that evening talking to Julian. When I mentioned to him how much I was enjoying our conversation, Julian replied (in the parlance of the day) “I’m digging it too!”

We became good friends during those carefree UBC years. Not too long after finishing university, Julian and I, each in our own way, began to look for a more peaceful life away from the city. It wasn’t until many years later that I realized that Julian’s background in rural England and Wales played a strong role in his desire to build a rural life in British Columbia. My then wife, Linda, and I joined the Argenta Land Co-operative and soon after I was delighted that Julian joined too. It was through his membership in the co-op that Julian met his wife, Josi.

In 1972, just a few months after my daughter Kristina was born, Linda, Kristina, and I drove to Argenta to attend a Co-op meeting and we had nowhere to stay. Julian was living in a tepee on the beach beside Kootenay Lake and he welcomed us to stay with him, so all four of us slept in his tepee for several nights. Julian also invited us to have dinner with him which we gladly accepted. The menu was soybean stew but Julian had forgotten to soak the beans earlier in the day. With an “Oh well,” he proceeded to cook the un-soaked beans for thirty minutes and then served them. They were still as hard as rocks so we all went to bed somewhat hungry, but the company was great!

Realizing that I wasn’t cut out for life in the countryside, Linda and I gave up our membership in the Co-op within a few years. But Julian loved the rural life in Johnsons Landing and around Kootenay Lake. He felt very much at home cultivating survival and wilderness skills, and even ran a trap line. Julian and Josi’s two children, Rowena and Callum, were born during the family’s time in Johnson’s Landing.

Julian and I kept in close touch during his Johnsons Landing years. I gave him a key to our house and when he passed through Vancouver he usually stayed with us. One such occasion was when Julian and Josi embarked on their adventure to Nepal. Another was when the whole family, including the two young kids, travelled to Britain so they could get to know Julian’s family. Julian and Josi had the kids run around the local park so that they would be tired enough to sleep on the flight. Once, when I was out of town, Julian let himself into the house not realizing that another friend was staying there. Fortunately his charming personality convinced the other guest that he wasn’t an intruder!

Julian’s trips to Vancouver became more frequent and finally he felt he had to leave the West Kootenays, because it was so difficult to make a living there. He settled in Victoria and he and I saw more of each other. Our friendship deepened as the years went by, and we shared personal ups and downs. Julian and I were always there for each other, as he was for all his many friends.

When I quietly resigned from a business venture, Julian protested that they should be “wining and dining” me. He was equally supportive when I had serious disagreements with my synagogue, saying they should appreciate me more.

Similarly, Julian shared with me difficulties he had with some of his employers over the years and I did my best to be equally supportive. I resented that some of his employers appeared to be taking advantage of him. He displayed a great deal of integrity in those situations. In his important work as an anthropologist Julian always tried to be objective and he worked with both First Nations and industry to try to find common ground. He had a keen sense of fairness and was disappointed if employers stretched the bounds of what he felt was right.

Anthropology was an excellent field for Julian and he parlayed his anthropological expertise into an inter-disciplinary approach that served him and his many interests well. In the early 1980s he was invited to spend two years in Nepal advising the government on economic and other policy issues. (He had become good friends with the future king of Nepal at Eton, but of course the offer was based on Julian’s own merit.)

Julian became a life-long friend to his academic advisor, Ken Burridge, and, when in Vancouver, rarely missed an opportunity to visit his mentor, even when Ken was in his 90s. He also made a point of frequently visiting long-time family friends, the Dennises, in West Vancouver, which they greatly appreciated. Julian was very loyal to his many friends, and could be counted on as a source of support. His friends returned that loyalty.

After telling me that he couldn’t attend my 70th birthday party a few years ago, he surprised and delighted me by showing up at the last minute. He also attended Eleanor’s and my wedding with great enthusiasm. Julian was a consummate gentleman and he spent much of the evening dancing with Eleanor’s 83-year-old mother, Marjorie, who was delighted with Julian’s attention. Julian also got to know my mother, Annette, and we all had enjoyable visits together at her house on Thetis Island. My Mum was a great fan of his, appreciating his charm, his modesty, his politeness, and his unaffected and genuine manner.

I had a particularly warm friendship with Julian’s mother, Olwyn. The first time we met was in 1988 when I was travelling in Britain with Linda and Kristina. We took the train from London to Bishop’s Stortford to be picked up by Julian, and driven to Olwyn’s house and garden at White Roding. We were just in time for lunch. Lunch was lamb stew. Period. I was a vegetarian but I ate the meal so as not to embarrass my host. Ironically, I learned years later that Olwyn was a vegetarian herself but thought that serving meat was what a good host should do.

After lunch Olwyn gave us a tour of the exquisite garden, and Julian gave us a tour by foot of the surrounding area, ending up at the church. We also met her legendary gardener, George, and I considered it a great compliment when he pronounced me a “sensible sort of chap!”

Since then I had several more visits to White Roding with Eleanor, and one or two by myself. I considered a visit with Olwyn to be a highlight of any trip to England, and on two occasions I took the train to Bishop’s and met Olwyn at the station. She was still driving at close to ninety years old. We had an extended lunch together before I took the train back to London.

The last visit to White Roding was very memorable. Five of us — Olwyn, Julian, his sister Jane, Eleanor, and myself — sat around the lunch table, and after the meal, Eleanor interviewed Olwyn regarding her memories of the wartime food policies, as part of a research project that Eleanor was working on. The interview was a highlight for us, and I particularly remember two things that Olwyn said in support of the strict food rules. One was that they “always had enough to eat.” The other was her reference to Lord Woolton who, as Minister of Food, was in charge of the food program: “They made him a Lord but I thought he should have been beatified!”

I will never forget my visit to the Welsh family estate at Foeles. Julian and Olwyn were there with his uncle Charles and aunt Rosie, and I was travelling around Wales with Kristina and one of her university friends. We considered it an honour to be invited to stay at the estate for a couple of days. I had never seen a real English estate, and particularly touching and memorable was when early the next morning Julian gave me a personal tour of the fields and hedgerows. He explained to me about the complex ecosystem contained in the hedgerows. I didn’t realize until then just how knowledgeable and passionate Julian was about the British countryside and how to take care of it. I think he would have loved to be in a position to manage such an estate but it was not to be.

Julian and I remained in close contact as he took various jobs around the province with Indigenous leaders on Haida Gwai, with an anthropologist headquartered in Sidney, and his last job with an oil company, which paid well and allowed him to save for his retirement. I also enjoyed following him to several different residences in Victoria and Saanich, and since he was now just a ferry ride away, in Saanich or later on Salt Spring, I was able to visit him more often.

Julian’s English heritage continued to play a large role in his life, and his education at Eton was a formative experience. I realized this many years ago when I had the opportunity to introduce Julian to another Eton graduate. They established an instant bond and reminisced for hours. I was privileged to watch Julian play cricket in the Victoria league one lazy summer afternoon, complete with white uniform, wide brimmed hat, and afternoon tea during the break.

Some years ago, Julian and I realized our mutual love of Indian food and we enjoyed many happy Indian meals together, both in Victoria and in Vancouver. Julian was much more of a connoisseur than I was.

We continued to visit often on the telephone. When I called he would answer and I’d say a cheery “Hi Julian.” He would pause for a moment and then… “Harley…” I’ll always remember the warmth in his voice. Julian and I could and did talk about anything. We discussed our respective writing projects, and recently he asked me for feedback on an essay he wrote for the local archbishop about Christian evangelism, which he felt strongly against. He also shared with me his father Roger Wake’s touching eye-witness account of Dunkirk. No subject was taboo. We gave each other advice freely, and we talked about our personal lives, and our hopes and dreams.

Shortly before his surgery I arranged with a Salt Spring caterer to have dinner delivered to Julian, while Eleanor and I, with our own food in Vancouver, shared an extended dinner visit with him over Zoom. What a lovely evening we had.

That virtual visit was the last time I saw him. We had telephone conversations after that but he was often tired and the calls didn’t go much beyond a few minutes. I was privileged to count Julian among my closest and dearest friends for over fifty years. I shall miss him terribly. And I will never forget him — Harley Rothstein.

*

Dave Crossley. In my youth I was imbued with the glories of the better parts of the British Empire and an ideal of the “English gentleman.” Alas, many of the Englishmen who I encountered did not embody the standards which I had been raised to anticipate; that is until Julian appeared on Haida Gwaii. I very much appreciated the acquaintance of someone with his education and intellect, as well as his cultural heritage.

In any discussion of events and issues, his contribution would contain deeper information than many of us are aware of and it would be based on reason. He surprised me a few times and he did not pander to what a person might wish to hear. His contributions were valuable.

The Kootenays were important to both of us. I was in the third generation of our family to live in Nelson. Julian lived in the Kootenays for many years and, I am told, participated in the well-known counterculture there. I imagine that Julian would have regarded the dogmas of the “counterculture” from a larger cosmos though. Nonetheless, when I was demonstrating the stereo, his choice of music was “The Incredible String Band.” Among the things which he did to support himself were fur trapping and doing layout work for the now defunct Kootenay Forest Products.

Julian arrived on Haida Gwaii in the fall of 1994. He was employed by the Ministry of Forests as an Aboriginal Liaison Officer. This was 27 years ago in the history of the Province’s relationship with First Nations. The job was as challenging as can be imagined. In my humble opinion he could not have done his job better.

Julian was interested in the Haida culture and he genuinely appreciated the people he worked with. This is a difficult position to be in. A Liaison Officer becomes involved with his clients and empathizes with them, but he has to represent his employer’s policies, which might not be empathetic at all. Then the Liaison Officer must return to his office, bearing messages that his employer is not always delighted to hear.

One of Julian’s duties was managing a process that permitted the Haida to harvest the trees which were needed for cultural uses, primarily canoes and totem poles. The Haida are completely capable of harvesting their timber without government processes, but nonetheless.… I was a log scaler with the Ministry of Forests so I often accompanied Julian on his trips to the woods. A log scaler is someone who measures logs, and I helped Julian with his woods work. Those were pleasant diversions from my regular work, and I was especially happy to leave the political aspects of it to some lucky fellow such as Julian.

At the time I was very involved with fly fishing, which Julian was also interested in. He had some gear that was purchased in England, which interested me. We both had busy lives and should have gone fishing more, but we did get out a few times. Sometimes we were on rivers, but we also explored a couple of lakes. Julian forgave my fly fishing excesses and I was gifted with his good company. I learned a bit about nymph fishing in the lakes of Britain and Ireland from him.

Later I became heavily involved in volunteer work so there was no time for fishing, but we did get together occasionally. Julian retired from the Ministry and intended to spend his time writing. That did not work out as planned and he went back to doing aboriginal liaison work, but this time for industry. He worked for a consulting company out of Sidney for a few years and then worked directly for a natural gas company and lived in Smithers. After reading his book reviews, I think it was a loss to literature that he was not able to devote himself to writing!

It was sad to witness Julian’s health failing, just when he had assembled a nice home and an enviable retirement life on Salts Spring Island.

You are missed, old friend — Dave Crossley.

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster