1441 Oh, the good new hockey game

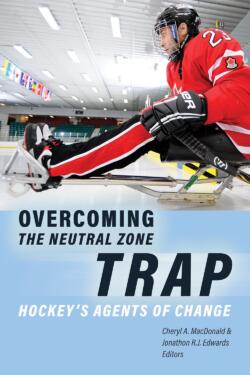

Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap: Hockey’s Agents of Change

by Cheryl A. MacDonald and Jonathon R.J. Edwards (editors)

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2021

$34.99 / 9781772125795

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

To anyone who watches the game with a critical eye, it should not come as news that the mainstream hockey establishment suffers from a hyper-defensive gatekeeper mentality. For too long now, the hockey world has enabled an insular cult of toxic masculinity, nostalgic racism, and restrictive rules for advancement that make the sport a less welcoming place for women, people of colour, sexual minorities, and the less privileged. As this book’s extensive source material reminds us, much has already been written in both mass media and scholarship about this problem.

To anyone who watches the game with a critical eye, it should not come as news that the mainstream hockey establishment suffers from a hyper-defensive gatekeeper mentality. For too long now, the hockey world has enabled an insular cult of toxic masculinity, nostalgic racism, and restrictive rules for advancement that make the sport a less welcoming place for women, people of colour, sexual minorities, and the less privileged. As this book’s extensive source material reminds us, much has already been written in both mass media and scholarship about this problem.

At the current moment, things seem to be looking up. “Hockey’s agents of change” have recently scored a few goals against the NHL’s macho, straight white male entitlement culture. (As TV personality Don Cherry, coaches Bill Peters and Mike Babcock, and several front office staff from the Chicago Black Hawks had to learn the hard way, there is no longer room in the NHL for blatant racism, psychological bullying, or conspiracies of silence around sexual assault). The game itself is opening up: Black, Indigenous and other players of colour are appearing more frequently on NHL rosters, women now occupy major positions in NHL front offices and on TV hockey broadcasts, and NHL teams all do outreach in their city’s respective LGBTQ2+ communities. Even mental health—long a taboo subject—has become mainstream fodder for discussion at the NHL level.

Despite these changes, there remain significant barriers to making hockey a truly inclusive sport. Much of the resistance has to do with the power of myth, of hockey’s central place in the Canadian identity. From parents and minor rec league officials all the way up to the NHL, and the mass media opinion-makers who cover it, hockey’s gatekeepers have shown an almost religious fervour in shaping and promoting a culture based on fixed ideas of who should play, how the game ought to be played, and who should succeed at it. Applied to the culture and institutions of the game itself, the “neutral zone trap” of the book’s title (in hockey, it refers to a much-maligned defensive strategy for stifling the other team’s offence) becomes a metaphor for hockey’s reactionary conservatism and resistance to change. To unpack all this, co-editors Cheryl A. MacDonald and Jonathon R. J. Edwards divided the book’s twelve chapters into three sections: Challenging Hockey’s Norms, Access and Support, and Masculinity and Sexuality.

*

Published by the University of Alberta Press and edited by professors of sports sociology and kinesiology at two Canadian universities, the book includes two chapters dedicated to legitimizing university hockey programs in Canada. And why not? One “trap” the book takes on is a systemic roadblock to success for talented North Americans who aspire to play the game professionally. For most non-Europeans, the only route to the NHL is major junior (Canadian Hockey League) or the U.S. collegiate system, either of which offers the best opportunity for NHL draft attention. The hockey program under U Sports, the national governing body of university sport in Canada, is mostly ignored by big league scouts, written off as the place where “careers go to die.” In their chapter, Cameron Braes and Edwards use qualitative analysis to explore current and former U Sport players’ assessment of the system’s legitimacy. Using four criteria—athlete development, the importance of education/scholarship opportunities, professional career opportunities, and reputation—they conclude that participation in U Sports is not a step backwards but “an alternative pathway to professional hockey while also gaining an education.” In her chapter, Chelsey Leahy examines the gendered structure of U Sport’s hockey programs. The men’s game receives disproportionately more funding, and the lack of body checking in the women’s game is used to justify budget decisions around the number of on-ice officials, medical staff, the provision of equipment, including sticks, et cetera.

Noah Underwood and Judy Davidson’s article about the U.S. National Women’s team’s successful 2017 player boycott of the Women’s World Ice Hockey Championship offers a compelling account of how women gained more power in hockey—but at a representational cost. On one hand, the team’s campaign was a major public relations and social media success: using the Twitter hashtag #BeBoldForChange, the players drew massive support for their demands of fair wages and equitable support for program development, reaching a settlement two days before the tournament began. But the campaign promoted traditionally heterosexual images of “the girl next door”, peddled in nationalistic American patriotism, and relied on class and race privilege to promote an essentially white feminist cause. After the team’s Olympic gold medal victory in Seoul, all but two of the players accepted an invitation to the Donald Trump White House—something they might have considered adding to their boycott list.

The power of national myth in suppressing non-white or otherwise marginal voices in hockey is well explored here. Non-Indigenous ally Vicky Paraschak’s “Skating toward Reconciliation” uses Call to Action #87 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which calls for public education about Aboriginal athletes in history, to explore Indigenous engagement with hockey in Canada. Drawing from the lessons of Thomas King’s The Truth About Stories and Richard Wagamese’s classic hockey novel Indian Horse, Paraschak reveals how Indigenous hockey players are not merely victims of the racism they experience while playing with settlers but the proud practitioners of a game they invented. Angie Abdou, the only literary contributor, recalls in “Karl Subban & Me” how she found common ground with the father of three NHL players despite her serious reservations about parenting and hockey culture. After touring together with their respective books, they came to the same understanding about the need to let children enjoy the game and not destroy their experience with parental expectations.

Another chapter by Catherine Houston, Kyle Rich, Tavis Smith and Ann Pegoraro examines dominant narratives of hockey culture on Twitter by comparing responses to two sensational news stories. The first involved the 2018 Humboldt Broncos bus crash. After several days of saturation media coverage of the tragedy (which killed sixteen members of the junior hockey team and injured another thirteen) and a nationwide fundraising effort to assist families of the players and other team members, Quebec-based writer and activist Nora Loreto tweeted that the maleness, youthfulness and whiteness of the victims played a big part in the media’s interest, and that so many other grieving parents and communities deserved justice but would never draw such attention. For this she received thousands of hateful replies, death threats, an attempted boycott of her work, and editorials accusing her of weaponizing identity politics.

By contrast, retired NHL player Daniel Carcillo’s string of tweets the same year, outlining his own traumatic experience of team hazing (in response to a news story about hazing incidents and abuse at St. Michael’s College School in Toronto), were greeted mostly with empathy despite his having revealed some of hockey’s darkest secrets. The authors suggest that Carcillo’s being part of the hockey family, an insider, made his intervention more acceptable than that of Loreto, an outsider to the game. Brett Pardy’s “Hockey Talks” outlines how the NHL has slowly begun to face the reality of mental health challenges. But while some players are willing to step forward as allies, most are still reluctant to be seen as role models living with mental illness. In his chapter, former Western Hockey League player Kieran Block describes his perseverance in recovering from a near fatal diving accident to embrace a form of hockey he can still play—only to be thwarted by rules declaring that he’s not disabled enough to qualify for sledge hockey.

*

For all the change sweeping through the NHL, compulsory heterosexuality has become the final sacred cow. Hockey machismo eschews emotional sensitivity while reinforcing stoicism, competitive hatred, and homophobic belittlement of opponents. Would The Hockey News republish Roger G. LeBlanc’s “Uncovering the Conspiracy of Silence of Gay Players in the NHL”? I doubt it: apart from Nashville Predators prospect Luke Prokop, who has yet to play a game in the Big Show (and whose own coming out of the closet last summer was likely too late for mention in this book), not a single active roster NHL player has ever publicly declared his homosexuality. And there’s a simple reason: a code of silence based on league consensus that an openly gay player would undermine everything the game is supposed to be about.

Drawing from interviews with league personalities such as Brian Burke and Georges Laraque, who confirm the existence of gay NHL players, LeBlanc uses his vast research on the subject—the bibliography is seven pages long—to invent a fictional Player X, who explains in testimonial passages why he doesn’t come out. LeBlanc’s use of the Conspiracy of Silence Model of social interaction, combined with fictional ethnography, explores the paradox of how and why such players remain in the closet even as their teammates join league initiatives like You Can Play, a program encouraging acceptance of sexual diversity in hockey. It’s a fascinating portrait of identity management: Player X, responding to the peer pressure of having to perform in the bubble of team dynamics, chooses to live a double life and suppress an essential part of himself so he can avoid the career-killing shame of being exposed as queer.

Former professional Brock McGillis, who never made it to the NHL, recounts his career in extensive interviews with the book’s co-editor, Cheryl A. MacDonald. McGillis, a goaltender from Sudbury, describes how his problems began just as he was about to become a first-round draft pick by the Ontario Hockey League’s Windsor Spitfires: instead of advancing, he needs time to recover from a broken hand suffered after getting into a fight when someone called him “faggot.” Later he ends up in Junior B and sustains several more injuries, all hockey related, while struggling in private with his sexuality. From torn meniscus and ankle ligaments to mononucleosis—which causes him to lose thirty pounds and miss a month of play—his body seems to be in rebellion. McGillis later concludes that these ailments were a psychosomatic response to shutting down his true feelings—all too familiar a memory for any reader who remained in the closet for several years after coming into self-awareness.

McGillis ultimately triumphs over his own self-loathing and is today a motivational speaker and sports training business owner. Like Black players disappointed by hockey’s anti-racism efforts, he’s glad that NHL teams hold Pride nights but finds the league’s diversity efforts a bit too performative: players only use sticks with rainbow-striped Pride tape during pre-game warm-ups, which are not broadcast. And the use of arena “kiss cams” that focus for amusement purposes on two male fans who happen to be sitting together only reinforces anti-gay attitudes. What the NHL really needs is diversity training across every team’s organization: from the front office and administration staff to the players, coaches and trainers.

What are hockey’s straight, white male gatekeepers really afraid of? The answer is femininity—especially any trace of it within themselves. University of Calgary kinesiologist William Bridel’s recollections as a gay figure skater victimized by hockey culture are deeply moving. Bridel recalls how the abuse he suffered while growing up in small town Ontario during the 1970s and 80s was exclusively heaped upon him by hockey playing boys, who — almost from the moment he first put on a pair of white figure skates at age six — bullied him and called him “queer, sissy, and faggot”. His observations as a non-hockey playing Canadian are coupled with an academic interrogation of the sport, its quasi-religious connection to national identity, and its harmfully obsolete notions of masculinity. His complete lack of interest or participation in the game at any level—he sat out Team Canada’s 2010 Olympic gold medal victory to teach a yoga class and, to this day, has never seen a complete game — makes him the ultimate hockey outsider.

Fred Mason rounds out this balanced collection with a look at the hockey enforcer as ironic victim of the sport’s cult of masculinity. From depression and substance abuse to the long-term impact of multiple concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, this chapter examines how the once feared enforcer, or “goon”, has become a disappearing breed. Through the prism of Lynn Coady’s novel The Antagonist and Jeff Lemire’s graphic novel Roughneck, Mason creates a profile of the enforcer as tragic figure trapped from an early age into expectations of violence because of his size or temperament. (“I was a thug from the moment I popped from the womb, or so rumour has it. Ten pounds, bruiser hands and feet,” Coady’s character, Rank, recalls.) Although Lemire’s enforcer, Derek, is Cree and suffers injustices of systemic racism and intergenerational trauma that a character like Rank will never know, both are raised by abusive fathers and are fated to continue their violent ways long after they’ve left the game behind. And both suffer from the same knowledge: that they were once paid good money to inflict short-term pain on others at a cost of long-term pain to themselves.

*

Daniel Gawthrop still plays left wing with the Cutting Edges, Vancouver’s LGBTQ hockey club, which he co-founded in 1994 after organizing the ice hockey event at Gay Games III in 1990. During the Vancouver Canucks’ 1994 Stanley Cup run, he gained brief notoriety when Don Cherry quoted his newspaper articles about Pavel Bure’s beauty and Cherry’s flamboyant wardrobe on CBC Hockey Night in Canada’s “Coach’s Corner”. Daniel is the author of five non-fiction books including The Rice Queen Diaries (2005) and The Trial of Pope Benedict: Joseph Ratzinger and the Vatican’s Assault on Reason, Compassion, and Human Dignity (2013), both published by Arsenal Pulp Press. His first novel, Double Karma, will be published in Spring 2023 by Cormorant Books. You can follow Daniel on Twitter at @dgawthrop and visit his website here. Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has previously reviewed a book by Hassan Al Kontar for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

10 comments on “1441 Oh, the good new hockey game”