1432 Sophia Chang and the Big Apple

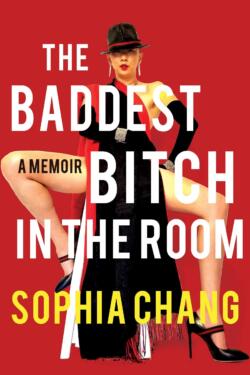

The Baddest Bitch in the Room: A Memoir

by Sophia Chang

New York: Catapult, 2021

$17.95 (U.S.) / 9781646220816

Reviewed by LiLynn Wan

*

The essence of autobiography is in creating identity, and Sophia Chang’s memoir, The Baddest Bitch in the Room, does just that. By writing her life story, she asserts: “I am defining myself and telling the world who I am” (p. 304). Her story begins with her parents’ difficult early years in Korea during and immediately after the Second World War, and their subsequent immigration to Vancouver, where Chang was born in 1965. She had a comparatively comfortable middle-class childhood, with both parents working at the University of British Columbia, her father as a math professor and her mother as a library assistant. Her childhood was marked by racism, growing up Asian in a dominant White culture in the 1970s, and she recalls the feeling of not being seen, an awareness of her physical difference, and rejecting her Korean language and culture. These challenges, she claims, are at the root of her compulsive desire for visibility that manifested in her unapologetic brashness as an adult and, subsequently, in the writing of this book.

The essence of autobiography is in creating identity, and Sophia Chang’s memoir, The Baddest Bitch in the Room, does just that. By writing her life story, she asserts: “I am defining myself and telling the world who I am” (p. 304). Her story begins with her parents’ difficult early years in Korea during and immediately after the Second World War, and their subsequent immigration to Vancouver, where Chang was born in 1965. She had a comparatively comfortable middle-class childhood, with both parents working at the University of British Columbia, her father as a math professor and her mother as a library assistant. Her childhood was marked by racism, growing up Asian in a dominant White culture in the 1970s, and she recalls the feeling of not being seen, an awareness of her physical difference, and rejecting her Korean language and culture. These challenges, she claims, are at the root of her compulsive desire for visibility that manifested in her unapologetic brashness as an adult and, subsequently, in the writing of this book.

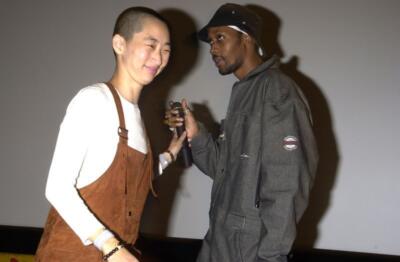

Best known for her career in the late 1980s and the first half of the 1990s as a hip-hop music producer, director, and manager, Sophia Chang’s love for music and dance was apparent from a very young age. In her last year of high school, Chang was introduced to hip-hop, which provided a voice for her angst, as “the first time [she’d] seen people of color telling their own stories” (p. 26). In 1985, on a trip to New York City, she met Joey Ramone by sheer luck of being in the right place at the right time and had the confidence not only to talk to but also befriend him. She claims, “that single act of fearlessness” was her “first big networking move” (p. 35). This combination of luck and fearlessness, as well as her remarkable networking skills, propelled Chang through an extraordinary career in the music industry, beginning with her move to New York City at the tender age of 21, where she started working for Paul Simon. In 1989, she got a job as an assistant in the Alternative Music Department at Atlantic Records and was quickly promoted to head of marketing. Later that year, she was given the opportunity to work A&R (Artists and Repertoire) at Jive Records, which meant the chance to work directly with artists. It was in this capacity that she found her way into the hip-hop world. In 1993, Chang was introduced to the nine members of the Wu-Tang Clan, their music, and their world. The relationships she formed with Wu-Tang were a defining moment in her life. As she states repeatedly, she was “raised by Wu-Tang.”

Although her journey from a comfortable middle-class life in Vancouver to the gritty world of hip-hop in New York City is certainly remarkable, Chang doesn’t actually offer much insight into her professional life in the music industry. Instead, she focuses on her often awkward and seemingly dependent relationships with the many men in her life. It is clear that Chang intended her autobiography to be inspiring to women, and women of colour in particular; and I believe that she believes her memoir represents some form of feminism and female empowerment.

However, the story of Chang’s impressive and unique career in the American music industry is compromised by the way she describes her relationship with the various members of Wu-Tang and other men in her life. Throughout her narrative, Chang positions herself as a woman in relation to men as either an object of desire, or as something to be protected, and often as both. Her sense of identity seems to be dependent on validation from the men she surrounded herself with. She describes her relationship with Wu-Tang in terms of ownership and possession, wherein “Wu-Tang didn’t just love me, they claimed me.… They made it clear to their crew and the world that Sophia Chang, this petite Asian woman, was theirs” (p. 78). She repeatedly refers to her own physical stature as petite or small, in contrast to her descriptions of Wu-Tang members as big, broad, tall, and strong. She imagines these men as her “bodyguards,” and the Clan as “protection.” With the Clan watching over her in this way, Chang declares, “finally, I felt I was fully seen” (pp. 90-91). As an Asian woman with an affinity for 1990s era hip-hop, I wanted so much to find this book empowering. Unfortunately, I can’t help but feel that these repetitive and emphatic physical descriptions only reinforce harmful stereotypes of both Asian women and Black men, and have the potential, albeit unintentionally, of exacerbating interracial conflict and misogyny.

Chang’s time with Wu-Tang was brief, and the bulk of this memoir is about her relationship with Shi Yan Ming, a 34th generation Shaolin master. Chang and Shi fall in love, even though Shi is already married to another woman and has two children whom he has left in China. In 1995, only two years after meeting the Wu-Tang Clan, her career path shifts when she decides to manage Shi Yan Ming and the USA Shaolin Temple in New York City. Chang recounts introducing Shi to the Wu-Tang Clan, and in particular the close relationship that develops between Shi and RZA (one of the Wu-Tang Clan members). She writes about their trips to China, her two pregnancies, and her foray into fashion in 2003 when she takes a job with designer Vivienne Tam. She also takes on managing RZA’s Hollywood career briefly. All this while she was still managing the Shaolin Temple – even through Shi’s dramatic detention in China, his affairs with other women, and the eventual disintegration of their relationship.

In 2004, Shi and Chang separated, and Chang returned to the music industry and single life. She includes very little about the industry in her memoir, and too much about her dating life, which she describes as a “manhunt,” with sex as “a notch on [her] motherfucking belt” (p. 186). Chapter 9 is appropriately titled “The Juggling Act.” Here, Chang means that the juggling act was balancing dating, her kids, work, and her workout schedule at the gym. For the reader, this chapter is also a juggling act. At one point, within a dozen pages, Chang offers painfully detailed descriptions of having phone sex, an account of her son’s soccer practice and her attempts to counsel her kids against bullying, discussions of how many men she had slept with and why that does and does not matter, grocery shopping, managing and then getting fired from managing the musician Raphael Saaqid, and her various dating and sexual exploits. It is a confusing read.

The Baddest Bitch in the Room is an interesting account of one woman’s extraordinary life and career, and there is no denying Sophia Chang’s courage and brazenness, her work ethic and her bold personality. Chang’s brand of sexual empowerment may be interpreted by some as liberating and inspiring, and her story is one that exudes a passion and ferocity that is to be commended. I appreciate what Chang has accomplished in her life, especially as a woman of colour in a male dominated industry, and the book does offer some interesting insights into the early years of hip-hop. But I find her approach problematic, in light of her assertion (stated explicitly in the final chapter of this book) that her story is intended to empower women. She appears to champion sex-radical feminism and advocates unapologetic sexual forwardness, but she misses the potential of addressing a larger cause. Sex-positive or sex-radical feminism is not just about individual sexual freedom but needs to align with broader issues of social justice, like the decriminalization of sex work and moving beyond heteronormativity, in order to function as activism. Her stereotyping of Black men is similarly problematic and ignores the larger systemic and historical issues at play, including the position of Black women, which she does not address or align herself with. This book is not particularly well written, and the narrative tends towards self-aggrandizement. Most problematic, however, are the many ways Chang’s memoir falls short of being the feminist endeavour that she claims it is.

*

LiLynn Wan is a full-time potter currently living in Portuguese Cove, Nova Scotia. She produces functional dinnerware, kitchenware, and tea-ware. Her work is inspired by classical Chinese, Korean, and Japanese ceramics, aesthetics, and philosophies of craft. She holds a PhD in Canadian history from Dalhousie University. Editor’s note: LiLynn Wan has also reviewed books by Santo Mignosa, Brooke Xiang & Tyler Mark, Jim Wong-Chu, and Tina Loo for The Ormsby Review

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster