1405 Colonialism corrective

TELEVISION DOCUSERIES REVIEW: British Columbia: An Untold History

by Kevin Eastwood, Writer and Director

Burnaby: British Columbia’s Knowledge Network, 2022

Reviewed by Patrick A. Dunae

*

Knowledge Network, ‘British Columbia’s public educational broadcaster,’ has produced a compelling documentary series entitled British Columbia: An Untold History.

Knowledge Network, ‘British Columbia’s public educational broadcaster,’ has produced a compelling documentary series entitled British Columbia: An Untold History.

The production qualities are superb. Each episode of the four-part ‘docuseries’ opens with a sweeping panorama of islands, mountains, rivers and valleys. As the viewer is drawn into the vista, a narrator intones: “You are looking at what some people call British Columbia. This place has had other names and even today, it’s called other things by different people. The truth is, a name is just an idea, and British Columbia is an idea that is still relatively new” (Episode 1, frame 1 minute, 20 seconds; hereinafter E1, 1:20).

The docuseries was commissioned by Knowledge Network to coincide with the 150th anniversary of British Columbia joining Confederation in 1871. But this is not a celebratory chronicle. It is intended to be a corrective “platform” for recounting “stories of Indigenous, Chinese, Japanese, South Asian and Black communities” that have not been prominent in previous narratives. Hence the sub-title, An Untold History. The programme aired in October and November 2021 and is now available for streaming on the Knowledge Network website, knowledge.ca

Knowledge Network has been producing high-quality programmes on historical themes for most of its history. Although the network officially celebrated its fortieth anniversary in 2021, its lineage goes back ten years earlier, to 1971 when the provincial Department of Education established its Audio-Visual Services Branch. This was truly an instance where ‘video killed the radio star,’ since the new branch, which specialized in making videos for public schools, was descended from, and replaced, the Division of School Radio Broadcasts. In 1974, the Audio-Visual Services Branch became the Provincial Educational Media Centre.

In 1983, Provincial Educational Media Centre produced a three-part programme entitled You Can’t Get There from Here. It told a story about BC’s entry into Confederation. It was researched and written by BC historian Juliet (Cooter) Pollard and directed by Rod Langley, an historian and playwright with many BC film credits. Library and Archives Canada cataloguers described it as follows: “Using a carefully researched blend of fact and informed conjecture, dramatic episodes and monologues help put a face on political and social history.” In the 1983 production, an Indigenous actor remarks that aboriginal people were not consulted when the Pacific colony negotiated Terms of Union with the Dominion of Canada. The issue is amplified in British Columbia: An Untold History.

Knowledge Network receives about half of its annual budget from the provincial government. (Additional revenue comes from donors, who are called Partners in Knowledge.) It has a statutory obligation, under the Knowledge Network Corporation Act, to “inform and educate British Columbians about their province and about issues that are relevant to them.” It is now mandated, by ministerial decree, to provide “broadcast programming that promotes equity, diversity, inclusion and anti-racism.” Further, its mandate is to “collaborate with independent, Indigenous filmmakers to create original stories and continue to increase opportunities to share Indigenous perspectives, as well as ensure BC’s culturally diverse storytellers are selected.”

The docuseries is directed and written by Kevin Eastwood, a Vancouver filmmaker who studied at Emily Carr University of Art + Design. According to the Official Press Kit for British Columbia: An Untold History, he is “an award-winning director, producer and writer” whose recent credits include Humboldt: The New Season, After the Sirens, and Emergency Room: Life + Death at VGH. The producer, Leena Minifie, of mixed blood (Gitxaala and British) descent, is a media, film and television producer and digital strategist based in Vancouver who specializes in works that “engage BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Colour] audiences.” The music was written by Cris Derksen, an Indigenous composer and cellist. Shane Koyczan, an Indigenous spoken word artist from Penticton, is the narrator.

Minifie and her team conducted interviews with Indigenous knowledge-keepers, academic historians and other expert commentators. Actors were engaged to enact historical episodes and possible historical scenarios.

Draft episodes were vetted by a diversity and inclusion marketing agency called AndHumanity. According to a CBC story, AndHumanity was hired to ensure that “people from the communities reflected in the documentary felt they were being authentically represented.”

Production for the British Columbia: An Untold History docuseries commenced in 2019, as part of a larger Knowledge Network initiative called the British Columbia Documentary History Project. The Project also created a series of short features entitled 150 Stories that Shape British Columbia.

As it happened, the timing for British Columbia: An Untold History was perfect – perversely so, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fortunately for the production company, Screen Siren Pictures, most of the camera work with interviewees and actors in the field was complete and ‘in the can’ before March 2020, when pandemic protocols halted production. Post-production tasks were undertaken by team members working remotely. Meanwhile, viewer audiences – whose stay-at-home members were curtailed by the lockdown – burgeoned. British Columbia: An Untold History was eagerly anticipated and its enthusiastic audience helped Knowledge Network attain a laurel as the third most watched broadcaster in British Columbia in 2021.

The first episode, entitled “Change + Resistance,” sets a tone for the series and asserts its premise that British Columbia is “an idea” rather than a geo-political entity. British Columbia is an idea that is open to interpretation and ultimately informed by stories. “Stories have always had the power to shine a light on who we are,” the narrator explains, “and all they ask is that we listen.” “The stories we’re going to tell aren’t all the stories you need to know. Some stories you may have never heard, others you may have never heard this way. But they help explain why this place is the way it is” [E1, 2:00].

While acknowledging that Indigenous stories have been told for millennia, the documentary avers that one story is most important. “If we’re going to tell the origin story of what we call British Columbia, we need to go back to one event – the Fraser Canyon War” [E1, 2:09]. That event took place during the 1858 gold rush. It was a short but potentially calamitous conflict that involved gold miners from California who threatened Indigenous people with annihilation. An all-out war between Indigenous warriors and white interlopers was averted by a truce negotiated by a Nlaka’pamux chief and the leader of a miners’ militia. Thus, genocide was avoided and annexation from US army intervention was prevented. The First Nations-brokered truce provided time for a dilatory British government to declare its sovereignty in the region and for James Douglas, who was governor of the neighbouring colony of Vancouver Island, to issue a proclamation on behalf of the British Crown.

History professor Adele Perry describes the pre-emptive action by Douglas as a questionable “act of colonial possession over the Mainland.” Indigenous historian and playwright Kevin Loring remarks: “In that moment of uncertainty, he [Douglas] sort of snuck in and declared it as a Crown Colony in order to stave off the American invasion. He doesn’t consult the actual [Indigenous] people who have been there forever, whose territory it is. He just sort of puts his flag down and says ‘This is ours.’ If that’s the foundation of this being what we call British Columbia, it’s kind of a fraud” [E1, 12:57].

The opening episode addresses the devastation of smallpox on aboriginal communities, injustice of colonial jurisprudence, inadequate allocation of Indian reserves, unwarranted laws against potlatch ceremonies and the deleterious effects of Indian Residential schools. The episode is prefaced by a trigger warning indicating that “the following program contains subject matter about Indigenous peoples, including their experience with residential schools in British Columbia. These stories may be upsetting or traumatizing to some audiences.” The warning is intended for residential school survivors but might serve as a caveat for non-Indigenous viewers who will be appalled by all aspects of colonialization depicted here.

The second episode is entitled “Labour + Persistence.” It “explores the history of labour and inequality.” The episode opens with another stunning aerial vista, as the narrator intones that British Columbia (as some people call it) is “a place where people have always worked.” Both “immigrant settlers and ancestors of the land itself” have toiled here. But the bountiful natural resources also “drew the gaze” of persons motivated by greed, “who paid their workers little respect and even less money” [E2, 1:46].

The history of labour, as recounted in this episode, is not an untold history. The history has been told before, and in a more comprehensive way, by Knowledge Network in a three-part documentary entitled Working People: A History of Labour in British Columbia. That documentary was first broadcast in 2013, not so long ago. It was written and produced by Erica Landrock, who is the supervising producer of British Columbia: An Untold History, and includes episodes narrated by Kevin Loring, aforementioned. Working People deals with racial discrimination while documenting the contributions of Indigenous workers and workers of Chinese, Japanese, African and South Asian descent. However, British Columbia: An Untold History excels in presenting dramatic reconstructions of some key events in provincial labour history, such as the shooting of Albert “Ginger” Goodwin in 1918. The circumstances and repercussions of Goodwin’s death are described vividly by Rod Mickleburgh, a labour historian.

Episode 2 discusses women’s suffrage and a partial victory achieved in 1917, when the provincial vote was extended to white settler women. Lara Campbell, an historian based at Simon Fraser University, observes that thirty years would pass before Indigenous women and adult female residents from China and Japan were enfranchised. The unjust obstacles that immigrants from Asia encountered are examined in Episode 3, entitled “Migration + Resilience.” The episode describes the “Battle of Burrard Inlet” in 1914, when migrants from British India, who had travelled on a ship called the Komagata Maru, were halted in Vancouver harbour and denied entry into British Columbia. Episode 3 offers a compassionate account of the unjust dispossession of Japanese residents in 1942. The episode also deals with the incarceration of Doukhobor dissidents in the 1950s and the influx of American “draft dodgers” in the 1960s.

Some viewers might wonder why newcomers from the United States, who came to British Columbia in order to avoid being conscripted for military service in the Viet Nam War, are included in this episode. Most of the “draft dodgers” (the term is used ironically in the series) were white, middle-class, well-educated males who did not suffer the indignities of racialized immigrants. The American war resisters are included here because they apparently brought a heightened sense of social activism and ecological awareness to British Columbia. Their untold story provides a segue to Episode 4, entitled “Nature + Co-Existence.”

In the opening frames of the fourth and concluding episode, the narrator remarks poetically that this portion of the globe (which some people call British Columbia) was “a unique place where the veins of rivers flow from snow-capped mountains into the ocean, only to evaporate and rain down again, creating lush rain forests that teem with life, an immaculate cycle that results in a bounty as seemingly endless as its beauty.” However, as the narrator explains, the “gifts of nature’s bounty” are fragile and finite, and “not everyone who has come to harvest them has cared about what happens next.” Within “a short period of time, the natural resources [of British Columbia] have been depleted” [E4, 2:17].

The episode describes how a succession of outsiders caused the near-extinction of otters and whales, the depletion of salmon stocks, and the destruction of old growth forests. Indigenous people in contrast have always had a symbiotic relationship with nature. In recent years, non-Indigenous environmentalists have benefited from Indigenous knowledge and, in some parts of the province, constructive policies have been implemented. But overall, the province is benighted environmentally. The episode provides many examples of environmental disasters, including the devastating consequences of a hydro-electric dam on the Nechako River that was built in 1951 by the provincial government and a multinational company, Alcan. The dam flooded a vast area of land and, in the process, eradicated the traditional homes and burial sites of the Cheslatta Carrier people. The film footage of the devastation is almost unbearable to watch.

Finding suitable archival film footage and images of archival photographs to illustrate the four episodes must have been a challenge. Many of the images were provided by the Royal BC Museum and Archives. Other images were acquired from distant repositories, including libraries and museums in the United States. Most of the illustrations are well-chosen. But a few images are questionable and out of place.

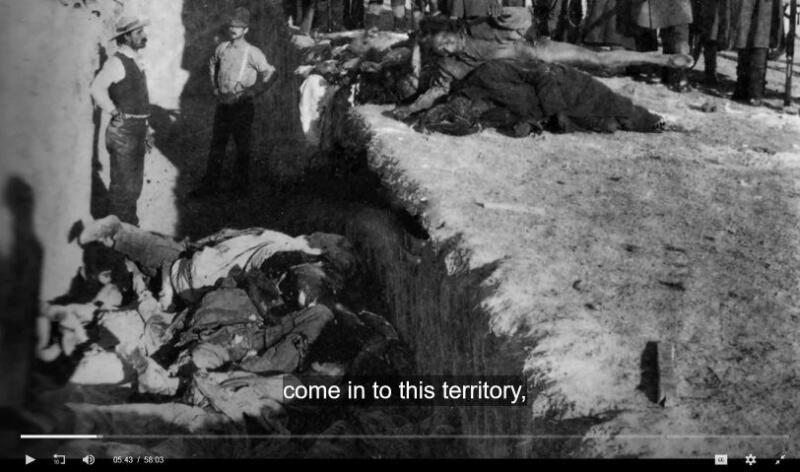

Controversial images are presented in Episode 1: “Change + Resistance,” where they accompany the sequence about the 1858 gold rush and Fraser Canyon War. The most contentious item is a photograph of a mass grave with a pile of Indigenous corpses. On the edge of the grave are more dead bodies, in unnatural repose, of Indigenous men. The bodies are about to be pushed into the mass grave. A group of white men brandishing rifles stands in the background surveying the scene.

This archival photograph is used in the Knowledge Network promotional trailer for the series, wherein a commentator (UBC historian Coll Thrush) states: “The gold rush is one of the few places where most historians agree that genocide took place” [Preview, 0:34]. In the opening episode, the gruesome photograph is on the screen for ten long seconds, as Kevin Loring describes the depredations of white miners – “who are accustomed to exterminating Indigenous people” – at Spuzzum [E 1, 5:45]. Professor Thrush then remarks: “The California [emphasis added] gold rush is one of the few places where most historians agree genocide took place. So, there was a lot of anxiety about this [influx of American gold miners], and also anxiety [among local Indigenous people] around violence, because they [white miners] are an armed population, almost entirely men…” [E1, 6:30].

In the trailer, Thrush’s reference to the California gold rush is edited out, so it appears that he is referring to a gold rush in British Columbia. Viewers will have to be paying close attention to the context of his remarks, when he and Loring and other expert commentators are describing events in 1858. To some contemporary observers, the influx of miners from California was undoubtedly alarming but mass murder and genocide did not occur in what some people call British Columbia.

As for the gruesome photograph, its provenance was determined with some difficulty. [I’m grateful to friends who helped me with this task.] The original image is in the Special Collections Libraries of the University of Southern California [Accession #10505]. The photograph shows the aftermath of the Battle of Wounded Knee (also known as the Wounded Knee Massacre) in South Dakota on 1 January 1891. The corpses are the bodies of Sioux warriors who had been killed by the US Cavalry a few days earlier, on 29 December 1890. By the time they were collected for burial, and when the photograph was taken, the dead bodies were frozen stiff. The armed men in the photo, who are wearing great coats and fur hats for warmth, are US soldiers; the white men standing in the trench are army contractors who were hired to dispose of the bodies.

This gruesome photograph has nothing to do with the events described in the Knowledge Network documentary series. Presumably, it has been used for shock effect to attract viewers. The image should have been flagged by one of the producers and called out by the historians who participated in the production. (The offensive image was added in post-production after the interviews with expert commentators were recorded. But the participants were invited by Knowledge Network to attend a preview of the finished documentary before the series aired and surely someone must have wondered about the relevance of this archival image.)

Expert commentators were interviewed in settings that enhance the dramatic qualities of the production. In the first three episodes, most of the interviews take place in museums and historic sites. There is some irony here, as interviewees describe the consequences of colonialism whilst sitting in the restored dwellings of colonial settlers. Moreover, several of the interviews with expert commentators are conducted in the Royal BC Museum [RBCM] – notably in the First Peoples Gallery and in the Old Town Gallery. As readers may know, those two very popular galleries within the RBCM have been shuttered. The exhibits within the galleries are being dismantled and the artifacts which were on display are being ‘decanted’ in order to ‘decolonize’ the museum. Interviews filmed in the now-closed and dismantled RBCM galleries will have an added, albeit unintentional, value for posterity.

My comments about the contentious image and the irony of some of the interview settings should not detract from the overall value of this documentary series. It succeeds admirably in what it sets out to achieve – namely to take an “unflinching look” at some of “the stories and events that shaped the province known as British Columbia.” It “uncovers Indigenous resistance to decades of brutality [and] the exploitation of migrant workers.” It “reveals continued resilience despite systemic racism and chronicles multi-ethnic efforts to protect the land.” It is testimony to how our historical thinking has changed in the last forty years, when Provincial Educational Media Centre produced You Can’t Get There from Here. That 1980s production was intended as a teaching resource in BC public schools. Knowledge Network’s new four-part documentary series should find a place in the modern curriculum. As well, British Columbia: An Untold History may be instructive to general viewers who want to learn about the construct of this province.

*

Patrick A. Dunae was born in Victoria and lives there now. He taught BC history at the University of Victoria and Vancouver Island University. Previously, he was an archivist in the Manuscripts and Government Records Division of the British Columbia Provincial Archives. Editor’s note: Patrick Dunae has also reviewed books by Linda Eversole, Bethany Lindsay & Andrew Weichel, Jenny Clayton, and Valerie Green for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1405 Colonialism corrective”

Director Kevin Eastwood’s objection to Patrick Dunae drawing critical attention to the use of a photo depicting U.S. history is unfortunately disingenuous: “We don’t suggest, either directly or indirectly, that the photo is from BC and no one watching would think that.” In my view the overwhelming majority of viewers would have drawn the opposite conclusion from the juxtaposition of the image and the audio statement that “The gold rush is one of the few places where most historians agree genocide took place.”

I have direct experience with making a documentary film about an aspect of BC history — The Spirit Wrestlers, about the Doukhobor and Freedomite experience in Canada — so I appreciate the difficulty of finding the right image to illustrate a key point. But if there’s a risk of misinforming the audience, especially on such a significant issue, caution should prevail. In this case, I’m convinced that using the image was not appropriate.

Following up on my review and the comments below — I think it is deceptive to use a photograph taken in 1891, showing the horrific aftermath of the Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, in an episode about the 1858 Fraser River gold rush. It’s not appropriate, in my view, to use this contentious image in promoting the documentary series, British Columbia: An Untold History.

Kevin Eastwood, the writer/director, says it is “quibbling” to question a photo that was taken “some years” after the gold rush. The photo was taken more than 30 years after, and more than 1,400 miles distant, from events described in the episode. That span of time and distance is not a quibble.

It’s disingenuous to say: “We don’t suggest, either directly or indirectly, that the photo is from BC and no one watching would think that.” Readers can judge for themselves from the trailer. In it, viewers are invited to “flip back the pages of history for an unflinching look at the stories and events…that shaped the province known as British Columbia.” Immediately after the narrator’s introduction, an on-camera commentator states: “The gold rush is one of the few places where most historians agree genocide took place.” The statement is followed by a scene showing torches setting fire to a structure of some kind, and then an archival photo of Indigenous corpses in a mass grave. The sequence occurs around the 30 second mark of the 2-minute trailer. The use and placement of this image, in my view, mars an otherwise commendable documentary film production.

I am saddened to read comments like those posted here. The series features over 2,000 archival images (all of which had to be sourced in the middle of a pandemic when a large portion of the world’s libraries and archives were closed), and includes perspectives from 70+ interviewees: a diverse array of historians, elders, knowledge keepers, writers, activists, community leaders and artists. BIPOC voices, and WOC in particular (ie. people traditionally excluded from other tellings of history) were given space to share their take on the history of BC. Given all of that, it’s little discouraging to hear that one image out of thousands could be given so much weight as to “undermine the credibility” of the rest of the project.

More importantly, I stand by the inclusion of the image. As Dr. Dunae himself describes, the photo comes after we hear Nlaka’pamux playwright Kevin Loring state how the invading Americans were “accustomed to exterminating Indigenous people”. The photo shows Native Americans who have been slaughtered by the United States Army. That’s what the image illustrates and the context it is used in: how Americans treated their Indigenous peoples. We don’t suggest, either directly or indirectly, that the photo is from BC and no one watching would think that. The speakers are clearly talking about how Americans treated Indigenous peoples during this era and then we show a picture of that.

And to say this photo has been used for “shock effect” and its use is “offensive” is hard to take seriously. Moments earlier in the same episode, we heard about Nlaka’pamux women being raped and killed by miners at Spuzzum, and in the scenes following we will hear about the bloodshed of the Fraser Canyon War, and later, how the Tŝilhqot’in warriors were hanged. And throughout the whole series we talk about countless other cases of direct and/or cultural violence that Indigenous peoples were subjected to at the hand of the settler/colonial state. Would Dunae criticize those descriptions as being included only for shock effect? Of course not. The history itself is what’s shocking and offensive, not the act of telling the viewer that it happened.

And that’s the same with the Wounded Knee photo; it just happens to be one of the only times in the entire four-hour runtime of the series where a visual depiction exists that matches the awfulness that we otherwise only ever hear described in words. These were all atrocities. I can understand some quibbling about the fact the photo is taken some years later, but I don’t believe that is anything so egregious as to warrant the disproportionate attention given to this one photo, much less to allow it to cancel out the merit that people here seem to give the rest of the series.

Despite this, I won’t let this one thing ruin a piece of writing that I think, on balance, is positive and which I’m otherwise appreciative of. But I guess I’m unusual that way. — Kevin Eastwood, writer/director, British Columbia: An Untold History

Dr. Dunae’s persistent research into the origins of the “genocide” photos reveals a serious flaw that undermines the credibility of a project devoted to correcting how aspects of British Columbia’s history have been told and retold. This flaw warrants a corrective response.

Thanks for this analysis. I hope people read far enough to find your important criticism of the inappropriate use of the US photograph. I also thought the imagery and description of the westward migration was a good description of the United States but was not the case with early British Columbia. I wish UBC would hire British Columbians to tell B.C. history.

Having enjoyed watching the series, “British Columbia: An Untold History”I was pleased to see the comprehensive review written by Dr. Dunae. I would especially like to congratulate him for his through research into the provenance of the “genocide” photos.