1397 Portraits of East Vancouver

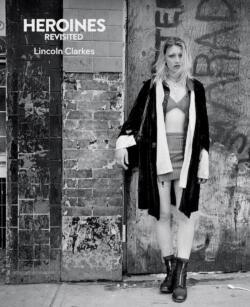

Heroines Revisited

by Lincoln Clarkes

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2021 (revised edition; first published 2002)

$48.00 / 9781772140712

Reviewed by Lani Russwurm

*

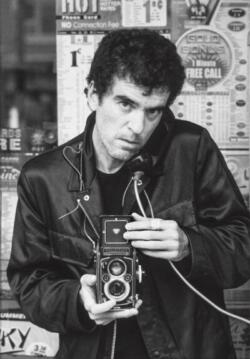

Lincoln Clarkes started his “Heroines Project” in the late 1990s when he began photographing women who use drugs on the streets of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. It took about five years and resulted in a few hundred portraits, gallery exhibitions, a documentary film, an award-winning book, Heroines: The Photographs of Lincoln Clarkes (Anvil Press, 2002), and now a second volume, Heroines Revisited.

Lincoln Clarkes started his “Heroines Project” in the late 1990s when he began photographing women who use drugs on the streets of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. It took about five years and resulted in a few hundred portraits, gallery exhibitions, a documentary film, an award-winning book, Heroines: The Photographs of Lincoln Clarkes (Anvil Press, 2002), and now a second volume, Heroines Revisited.

Clarkes’ choice of subject matter was part of a grim zeitgeist in Vancouver at the turn of the millennium. The late 1990s drug overdose crisis may seem almost quaint compared to the carnage caused by today’s poisoned drug supply, but it was serious enough to affect a sea change in how the drug issue was perceived in Vancouver and beyond. At the same time, the alarming number of women disappearing from the Downtown Eastside began making headlines and eventually saw the arrest and conviction of serial killer Robert Pickton. At least five of Clarkes’ subjects became Pickton’s victims (p. 234).

Two decades later and the adulterated illicit drug supply is now the leading cause of unnatural deaths in British Columbia (averaging seven per day as of this writing). Women continue to go missing from the streets, but are now recognized as part of the larger systemic issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) rather than victims of a lone killer.

In this tragic context, Clarkes’ photo project is as relevant now as ever. Heroines Revisited is a coffee table book of more than 200 black and white portraits of unnamed women taken in the streets, parks, and alleyways of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Accompanying the photographs is an interview with Clarkes and three essays that analyze and explore the context of the portraits.

Clarkes approached his Downtown Eastside subjects the same way he did when shooting fashion models and celebrities, and it shows. While some of the women bear obvious signs of a hard life, many of the portraits would not be out of place in a fashion magazine, except that the edginess in these images is not contrived. We see women with a sophisticated and deliberate style, many looking directly into the camera, projecting brashness and defiance as if to proclaim that they haven’t yet been beaten.

The real magic in Clarkes’ photographs is that the women’s vulnerability and humanity is equally on display alongside their toughness. Perhaps my favourite portrait is “Mother’s Day, Sunday, May 10th, 1998, Chinatown, 53 East Pender Street” (pp. 116-117). It shows fourteen women (the same number that were slaughtered in the 1989 Montreal Massacre), looking as if they had just let their guards down because the photographer was taking a bit too long to click the shutter. Their contrasting expressions, poses, and apparent personalities betray fourteen very different people with unique histories, sharing a moment and an experience that exemplifies the diversity and unity that runs through Heroines.

The first iteration of Heroines generated considerable discussion and controversy. In a neighbourhood used to being scrutinized, blamed, pitied, studied, and gossiped about, at first blush it may seem like just more Downtown Eastside “poverty porn” that accomplishes nothing except to reinforce harmful stereotypes. Heroines isn’t that. The accompanying essays make that clear, as do the photographs themselves. As a resident of Strathcona, Clarkes is himself a Downtown Eastsider, geographically if not culturally. He engaged his subjects, got to know them, compensated them for their time, and solicited their input. Royalties from the book go to the Elizabeth Fry Society, which helps vulnerable women caught in the justice system. By most measures, Heroines adheres to the mantra of neighbourhood activists: “nothing about us without us.”

The first iteration of Heroines generated considerable discussion and controversy. In a neighbourhood used to being scrutinized, blamed, pitied, studied, and gossiped about, at first blush it may seem like just more Downtown Eastside “poverty porn” that accomplishes nothing except to reinforce harmful stereotypes. Heroines isn’t that. The accompanying essays make that clear, as do the photographs themselves. As a resident of Strathcona, Clarkes is himself a Downtown Eastsider, geographically if not culturally. He engaged his subjects, got to know them, compensated them for their time, and solicited their input. Royalties from the book go to the Elizabeth Fry Society, which helps vulnerable women caught in the justice system. By most measures, Heroines adheres to the mantra of neighbourhood activists: “nothing about us without us.”

Heroines shows us there is beauty to be discovered by those willing to transgress the invisible class lines separating us from our neighbours. In a community routinely stigmatized as Vancouver’s seedy underbelly, the women featured are indeed heroines — the heroines of their own stories. In other words, they are actual people, not clichés or caricatures. Nor are they disposable. In such a wealthy and blessed city, it’s a travesty they’ve been treated as such.

*

Lani Russwurm is the author of the Past Tense Vancouver blog, and a researcher and writer for Forbidden Vancouver Walking Tours. He is the author of Vancouver Was Awesome: A Curious Pictorial History (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2013) and has contributed to numerous local publications and history projects, including Vancouver Confidential (Anvil Press, 2014). Editor’s note: Lani Russwurm has also reviewed books by Robin Brunet and Aaron Chapman for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster