1350 Making & taking Strathcona Park

A Journey Back to Nature: A History of Strathcona Provincial Park

by Catherine Marie Gilbert

Victoria: Heritage House, 2021

$26.95 / 9781772033588

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

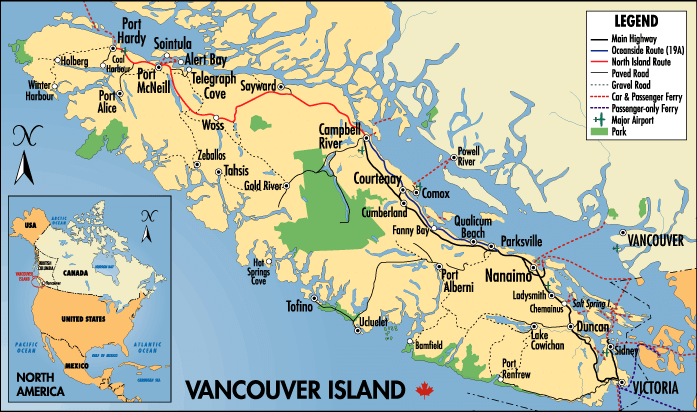

The past year in British Columbia has seen activism and protests centred on the forest industry and controversies over the logging of old growth rainforest. In such a political climate, Catherine Gilbert’s A Journey Back to Nature: A History of Strathcona Provincial Park carries a degree of relevance that may not be initially obvious. Indeed, the story of Strathcona Park, the first provincial park in British Columbia, is one of development, tradition, and potential just as much as land preservation. The legalistic and cultural complexity of the park, which is nestled in the interior of central Vancouver Island, straddling the cities of Campbell River, Courtenay, and Port Alberni, gives the reader an intriguing breadth of focus that reveals the depth of the province’s ecological and political heritage.

The past year in British Columbia has seen activism and protests centred on the forest industry and controversies over the logging of old growth rainforest. In such a political climate, Catherine Gilbert’s A Journey Back to Nature: A History of Strathcona Provincial Park carries a degree of relevance that may not be initially obvious. Indeed, the story of Strathcona Park, the first provincial park in British Columbia, is one of development, tradition, and potential just as much as land preservation. The legalistic and cultural complexity of the park, which is nestled in the interior of central Vancouver Island, straddling the cities of Campbell River, Courtenay, and Port Alberni, gives the reader an intriguing breadth of focus that reveals the depth of the province’s ecological and political heritage.

Gilbert makes it clear that the story of the lands that make up Strathcona Park did not begin with the park’s creation in 1911 by Premier Richard McBride. She emphasizes the importance of hunting in the island’s mountainous inland regions to Indigenous people, an example of an age-old practical use of the landscape. Indeed, one of the running themes of A Journey Back to Nature involves the competing uses of the amenities and resources of Strathcona Park. After an exploration (1894-96) by the Reverend William Bolton, government interest led gradually to the establishment of a provincial park in the hope that the beautiful coastal mountain scenery would rival Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies. But the onset of the Great War ended plans, including for a railway leading to a resort in the park’s mountainous interior.

Between the world wars, plans for a tourist destination dwindled and mining and logging activity increased due to economic pressures. Gilbert’s disappointment is palpable. After the Second World War, the W.A.C. Bennett government worked actively against the conservationist cause, introducing a hydroelectric dam on the Campbell River and a major mining concession at Myra Falls. Gilbert details the natural impact to the park of increased water levels on Buttle Lake and the largely haphazard attempt to harvest logs along the shoreline. She also considers the human impact of flooding Buttle Lake. While not heavily populated, the lake was inhabited by sometimes eccentric people whose history and character were soon lost to the forces of development. Previously seen as a potential mecca for tourists from around the globe looking to avoid the tired industrial world of the early 20th century, Strathcona Park instead succumbed to material forces when BC was dragged into global conflicts.

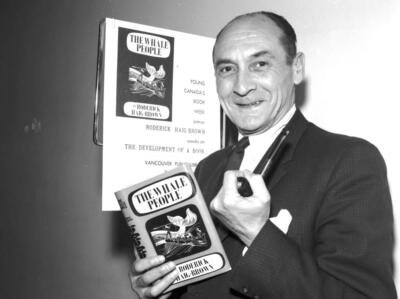

The ecological and preservationist principles that guided the park’s founding continued through the passionate work of local settlers such as the operators of Strathcona Lodge and Campbell River naturalist and writer Roderick Haig-Brown. Strathcona Park lodge, which had been moved up the shoreline during the flooding of Buttle lake, evolved from a private hotel to a semi-official information centre serving visitors who entered the park by road from Campbell River. Individual efforts in the Comox Valley to extend the park to include Forbidden Plateau, which for a time existed as an ad hoc ski haven, provide a similar example of people-driven passion replacing the inadequate work of government to preserve areas of outstanding beauty.

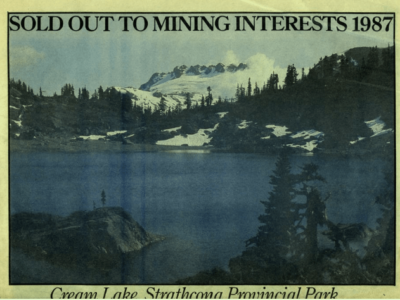

Gilbert celebrates the people who sought to preserve and publicize the park’s landscapes while lamenting their need to do so. This is nowhere clearer than in the provincial government’s attempt in 1987 to remove large sections of the park for industrial uses, which led to a blockade by the Friends of Strathcona Park. The blockade was ultimately successful in facilitating an independent review of the park’s future: should it be a site for mineral extraction or conserved for public enjoyment and appreciation? Ultimately, most of the park was conserved with some parts designated for extraction under the Strathcona Park Public Advisory Committee. The Friends of Strathcona Park achieved this through generally peaceful, if illegal, means.

In Gilbert’s history the blockade serves as the culmination of decades of community work to preserve the land in the face of decreasing official interest in what had been set aside in 1911 as a utopian natural vision of British Columbia’s future. Those sympathetic to the protests against government-sanctioned old growth logging on Vancouver Island, such as the Fairy Creek old-growth logging protests of 2020-21, may draw inspiration from the experience of the Friends of Strathcona in defending the park’s valued nature. Conversely, those less sympathetic to the current protests may take heart that a compromise was made and industrial activity continued within the boundaries of the park.

Catherine Gilbert’s A Journey Back to Nature is a deeply relevant history for its discussion of the competing forces of resource development and natural preservation in the discursive identity in British Columbia. This study of how a park with such hope and potential at the beginning of the century survived numerous attempts at substantial development will inspire, engage, and worry readers. While Strathcona Park may not yet be as popular as Banff, it remains a breathtaking destination for many who wish to explore the complex natural beauty of the province. And it was certainly worth fighting for.

*

Matthew Vernon Downey graduated in 2021 with an honours BA in History and Political Science from the University of Victoria. He is now an MSc candidate in international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Born and raised in British Columbia, he now lives and studies in Southwark, England. Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also reviewed books by David R. Gray, Grant Evans, Terry Reksten, and Ken Mather for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1350 Making & taking Strathcona Park”