1304 Blunt portraits & candid memoir

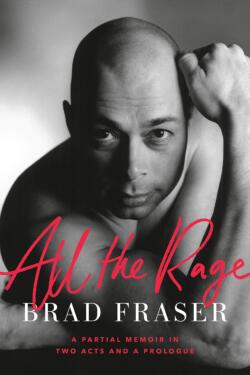

All the Rage: A Partial Memoir in Two Acts and a Prologue

by Brad Fraser

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Doubleday Canada), 2021

$34.00 / 9780385696371

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

One of the recurring delights of All the Rage is a multi-faceted storytelling technique that reserves a little something for everybody. Whether Brad Fraser is reminiscing about late nights of sex, drugs, and nightclubs or recounting arts funding applications and meetings with producers, he knows how to stage a lively scene.

One of the recurring delights of All the Rage is a multi-faceted storytelling technique that reserves a little something for everybody. Whether Brad Fraser is reminiscing about late nights of sex, drugs, and nightclubs or recounting arts funding applications and meetings with producers, he knows how to stage a lively scene.

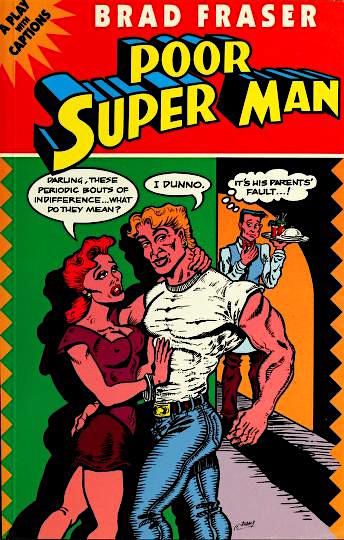

Addressing about four decades (1959-2000), Brad Fraser’s “partial memoir” traces the path of an erratic and hard-won success arc — starting with early misfires (like With Love from Your Son, from the late ‘70s, which Fraser remembers as “a cliché-ridden potboiler only a young man with a strong sexuality and little experience could think was original”) and pausing at 1994’s Poor Super Man (which Variety called “a remarkable piece of writing”) and 1998’s Martin Yesterday (as Fraser recalls, “Variety ran a scathing review by a local reviewer whose closeted but predatory behaviour I’d written about a number of times. Martin Yesterday was the talk of the town but not in a good way”).

Fraser organizes the book with chapters that chronicle the origins and intense revisions of each play; the chapters outline the fraught rehearsals and bumpy receptions too. In his telling, theatrical productions in Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec were hand to mouth affairs, and Fraser paints a vivid picture of not only the immense challenges of mounting outspoken, feather-ruffling productions but the sheer grind of the one-man show of hustling for cheap lodgings and extra shift work to keep barely afloat.

Readers not altogether fascinated by the ins and outs of play-staging across thirty years (and Fraser’s accounts are often detailed: although setting aside paragraphs to list casts of plays staged thirty years ago might be accurate, it drags down the narration) will nevertheless be impressed by his portraiture. Typically, it’s blunt, as when he recalls his Edmonton high school’s performing arts program: “We had two teachers, Billy Bob Brumbalow, a flamboyant Texan who was cagey about his sexuality, as teachers had to be in those days, and Don Pimm, a Burl Ives lookalike who assaulted many young women throughout his career as a teacher with impunity, as they did in those days”). And, years later, here’s another instructor: “It was absolute torture. Not only was she hard to understand, she was also boring. By the time she was finished, all existing energy had been sucked out of the room.” Democratic, though, Fraser never neglects to include himself — from “Also, I was often an asshole” to “I was an authoritarian control freak.”

Fraser assesses his plays dispassionately, and often identifies their weaknesses, with the earlier ones in particular suffering from ambition that was unmatched by skill. And he’s as forthright about his assorted non-professional dramas (weight gain, bad posture, hair loss, years of dental work), as he is about his gnawing appetite for drugs and alcohol, his heartbreaks and sexual adventuring, and his “nightmare” fiscal situations. The candour has a disarming effect, as though Fraser is in on the joke. When, for instance, he writes, “While swilling beer and snorting coke one evening, we decided it was time to move in together,” the eventual messy breakup feels as fated as a punchline.

As a strong personality with a self-acknowledged quick, cutting wit and confrontational style (as well as a tendency to revel in the power of abrasiveness), Fraser discloses that he had more than his fair share of conflicts, especially with journalists, other professionals in the theatre, and assorted elites that he understands to have regarded him as a gauche outsider that needed to play by their WASPy rules. Throughout All the Rage, conflict with various authorities forms a subtle leitmotif — reflected in Fraser’s anger and bitterness for the heterosexual mainstream and disdain for “nice people in the Canadian theatre [who] didn’t upset other nice people even if it meant producing mediocrity.” He “wag[es] war” with powerful enemies, including reviewers, and remembers being on the outside while looking in: “I’d been judged ungrateful, and if there was anything the Canadian elites hated, it was an ungrateful faggot.”

“Bastard Born,” the prologue, represents the best writing of the book. It opens with an elegant and poignant but also carefully measured paragraph:

My mother had been sixteen for three weeks when I was born in 1959. My father was eighteen. They’d met at a dance less than a year earlier. They were two sides of the same coin. Wes was the loud, manipulative bully; Sharon was the quiet, passive-aggressive controller. Neither was what the other needed but they were both what the other wanted. Both had quit school before completing the ninth grade.

Under thirty pages, the account offers heart-rending episodes of dysfunctional family traits, marital up and downs (mostly downs), sudden moves to “an endless succession of rental properties” and motel rooms in rural British Columbia and Alberta, all felt by a smart, creative boy who read anything he could find — from comics and Playboy to Little Women — while living with an emotionally distant and yet volatile father who expressed disappointment that his son wasn’t masculine enough. When name-calling (“Faggot!”) turned to physical blows, Fraser learned to use words to outwit his father, who only knew the power of physical intimidation.

All the Rage, as title, riffs not only on Fraser’s eventual fame, but the rage burbling within him. He concludes that portrait of the artist as the young queer Albertan with, “I knew that my upbringing had instilled a tremendous anger within me and that if I didn’t find a way to channel that anger constructively it would end directed at those around me or myself.” That “psychic trauma” only intensified over the early era of AIDS, an “intense period of shock and fear.”

Relatedly, there’s also “Disappearing the Queer,” an epilogue notably absent from Fraser’s subtitle, “A Partial Memoir in Two Acts and a Prologue.” Its position is clear from the opening sentence: “Straight disappear queer people.” Fraser surveys two millennia in which societies have “disappeared their queers through censure, persecution, and death”; and he reaches the conclusion that these acts of erasure are ongoing, whether the players are cultural norms, oppressive governments, “so-called progressive straight people,” or queer community members themselves. And before stating “I will not be disappeared,” Fraser celebrates his victory against social forces that sought to silence or discount him, his art, and his way of being in the world. The statements crystallize ideas both explicit and implicit across the preceding 330 pages: Fraser’s art, his character, and his life’s work are intimately bound to “being queer in a straight world.”

It’s a commonplace to mouth the words that queer has become wholly normalized — queer marriage, queer divorce, queer politicians, RuPaul beaming a million episodes across the globe. As far as liberationist politics go, the work, in that view, is complete — and what a success story! Pondering a lifetime of experiences from the vantage point of his seventh decade, Fraser reaches a considerably different verdict.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, was published in October 2021 with Now or Never Publishing — and reviewed here by Geoffrey Morrison. A previous book, Oldness; or, the Last-Ditch Efforts of Marcus O, was reviewed by Dustin Cole. Editor’s note: Brett Josef Grubisic has also reviewed books by Robert James O’Brien, Kevin Holowack, Sarah Mintz, Cedar Bowers, Glen Huser, Dustin Cole and George Ilsley for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1304 Blunt portraits & candid memoir”